To Elaine, Lewis and Eleanor

for their monumental love and support

The final decades of the nineteenth century marked a change in the perception of the bicycle and bike racing. Thanks in part to the invention of the freewheel and John Boyd Dunlops release in 1888 of the first practical pneumatic tyre, the bikes use as a means of transport became widespread, stimulating public enthusiasm for the fledgling racing scene. Initially, that interest was largely sated by events staged on wooden tracks, which sprang up all over the developing world as towns and cities endeavoured to demonstrate their dynamism and provide diversion for their inhabitants. From the 1890s, though, road racing began to gain an increasing following.

In Europe, the stimulus for the discipline came primarily from the establishment of BordeauxParis and ParisBrestParis in 1891. The former extended to 560km, the latter to twice that. In the modern era, such races would be split into stages run over successive days. Yet, these two mammoth events were effectively non-stop, no allowance being made for eating or sleeping. They were unmistakeably epic and attracted huge popular interest in France and beyond.

In the final decade of the nineteenth century and the opening decade of the twentieth, hundreds of races sprang up as cycling fans attempted to emulate the two great French events. Towns and cities endeavoured to raise their profile and newspapers tried to put each other out of business. Most of the races only lasted a year or two, but others gained a foothold and became well established, most notably ParisRoubaix, which had been founded in 1896.

Just as BordeauxParis and ParisBrestParis had done, the unveiling of the Tour de France in November 1902 changed everyones perception of what a bike race could be. It was, after all, the first multi-day stage race. However, rather than killing off single-day races such as Roubaix, the Tour prompted another wave of interest and investment in bike racing. Manufacturers prospered, teams were established, and, in the years leading up to the First World War, the racing calendar began to take shape.

The Tour de France dominated it, but one-day races also flourished, particularly in the great heartlands of the sport France, Italy and, a little later, Belgium. Over subsequent decades, MilanSanremo, the Tour of Flanders, ParisRoubaix, LigeBastogneLige and the Tour of Lombardy have become cyclings pre-eminent Classics, as the leading one-day races have long been known. More recently, they have been described as The Monuments of the sport, because they stand out as the races all professional riders aspire to win, alongside the grand tours and the World Championship.

Although they might not have the significance of the golf majors or the grand slams in tennis, they do offer a significantly different, more balanced and more immediate test than the Tour de France, Giro dItalia and Vuelta a Espaa, where endurance counts above all. Those three-week races may feature the fastest sprinters, the strongest time triallists and the best climbers, but youre unlikely to see Mark Cavendish, Fabian Cancellara and Vincenzo Nibali all racing eyeballs out for victory on the same day. Fans turn to the Monuments for that rare thrill, and it is that quality combined with their glittering history that makes the five races mentioned in the previous paragraph so special.

Each Monument provides a very different test and, like the Tour, each of them has its great exponents, legends and distinctive battlegrounds. Standing on the fearsome cobbled climbs such as the Oude Kwaremont, Paterberg or Koppenberg provides not only a spectacular perspective on the Tour of Flanders, but also a fascinating insight into the Flemish people, whose culture was to a large extent reasserted via this event and bike racing. Roubaix, dubbed cyclings last great folly by its one-time director Jacques Goddet, has its hellish cobbles. Lombardy features the iconic climb to the cyclists chapel of the Madonna del Ghisallo and what is undoubtedly the most beautiful course of the cycling year.

Over the last hundred years and more, the Monuments have provided many of cyclings greatest stories, from Sanremos fourth edition, when only four riders completed the 288km course, to Roubaixs long battle against road gangs determined to resurface every cobble in northern France, to the blizzard-hit 1980 edition of Lige that left winner Bernard Hinault with permanent loss of feeling in some of his fingers.

According to one of cyclings pre-eminent historians, Serge Laget, these races are not there as padding or preparation, and even less as consolation. Quite the contrary, in fact. They have their own existence, their own richness, a fantastic history and a legitimacy that goes back to the very origins of cycling. Unlike the Tours 22-day soap opera, where might always tends to be right, the Monuments are cyclings unpredictable thrillers, where almost any member of the peloton can prevail given the right combination of great form, tactical nous and simple good luck. Every rider starts them thinking, This just might be my day...

It is the most beautiful Classic on the calendar, Michele Bartoli, two-time LigeBastogneLige winner, told Procycling in his pomp in the late 1990s. Its the only race where you can be certain that the riders on the podium are definitely the strongest. In other races being clever can make up for a lack of strength, but not Lige. What matters in Lige is pure physical strength. Tactics count for much less.

When he spoke of the races beauty, Bartoli was referring to the purity of the challenge Lige offers, rather than the rolling landscape in the Belgian Ardennes where it takes place, although the terrain is impressive. For the Italian and many others, Lige is the one Classic where the best one-day riders and the best stage race riders meet on terrain that suits them both to an extent, without favouring either.

Founded in 1892, Lige is the longest-standing of the Monuments, which has earned it the name La Doyenne The Old Lady. Among the races on the modern international calendar, only MilanTurin has a lengthier history, the Italian one-day race dating back to 1876, although that first edition was a one-off. The sister race to Sanremo and Lombardy didnt establish itself fully until after the Great War.

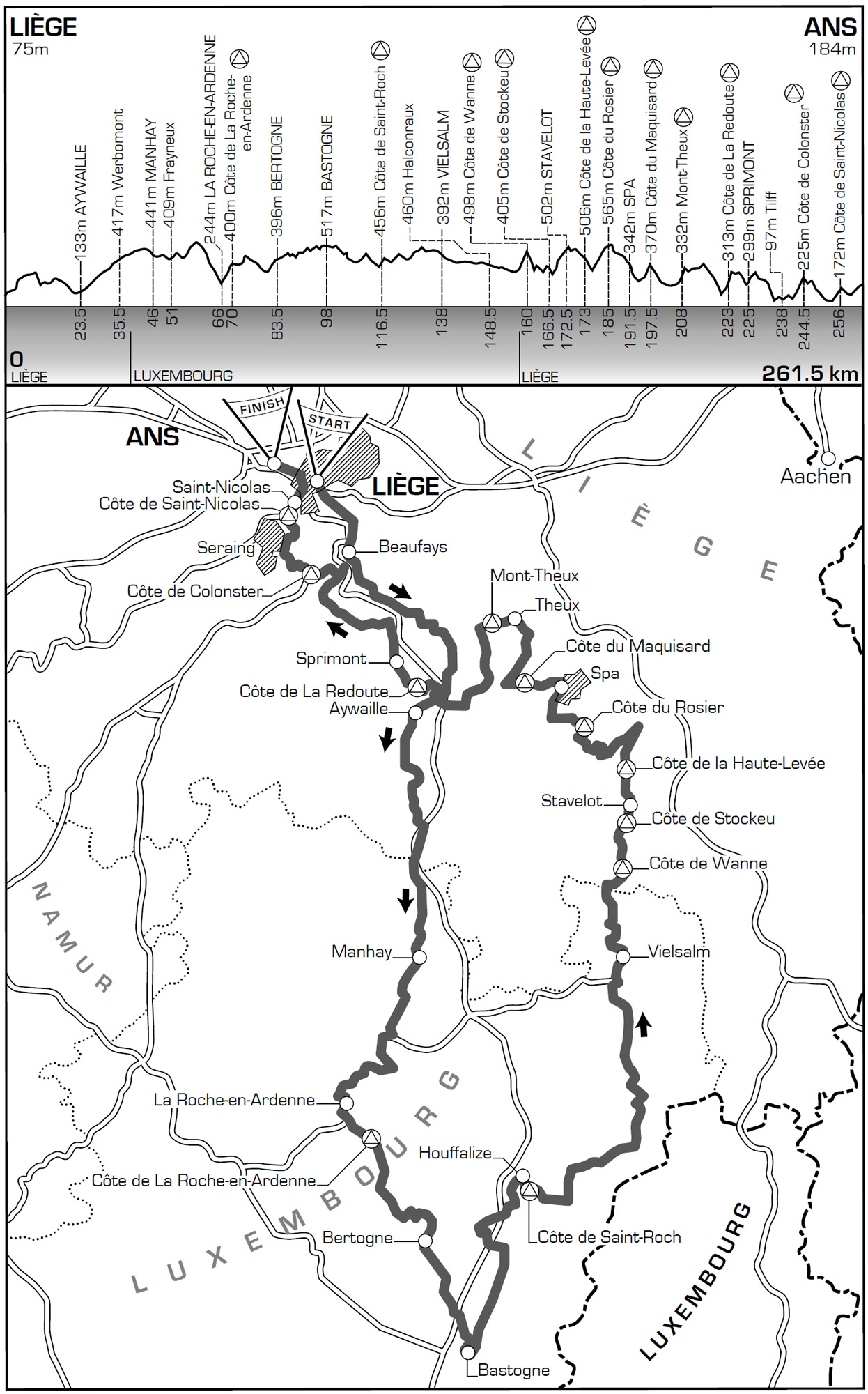

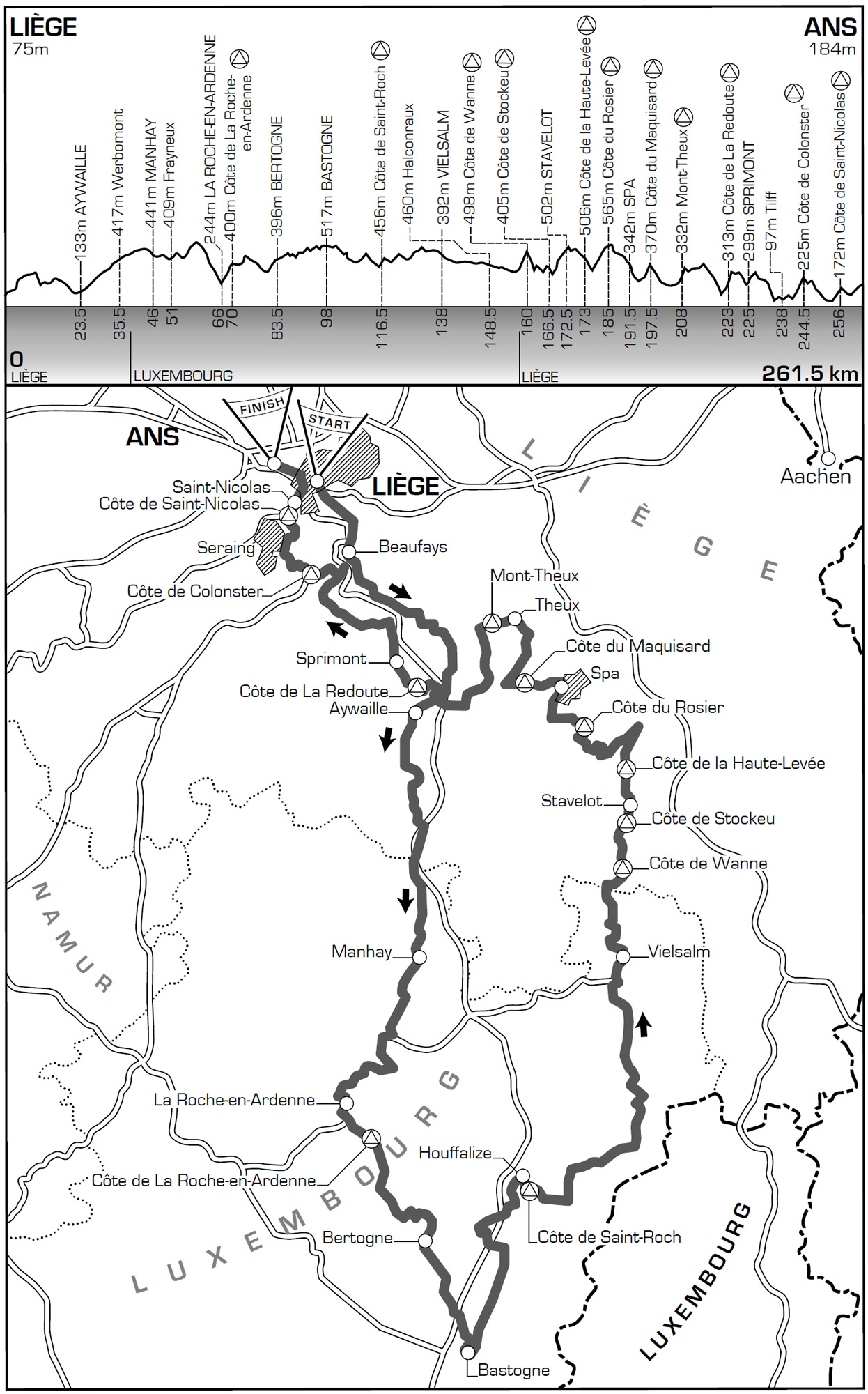

Lige also had a rather erratic start. Uniquely among the Monuments, impetus for its founding came directly from the first running of BordeauxParis and, particularly, ParisBrestParis in 1891. Members of the recently established Lige Cyclists Union theres no mistaking the British influence in that name had plans for an epic 845km LigeParisLige event. They decided the first step towards that would be a 250km test race from Lige to Bastogne in the south of French-speaking Wallonia and back again. Bastogne was selected as the turning point because the race organisers could get there on the train to make sure the competitors completed the outward leg of the course before they returned north.

In the end, the mooted LigeParisLige event never materialised, whereas the preparation event for it became relatively well established. The first edition, which was for amateurs only, took place on 29 May 1892. At 5.39 that morning, a few hundred spectators gathered on the Avenue Rogier in central Lige to cheer off 33 intrepid riders and their pacers, whose task was to keep the speed as high as possible for their racer. The course took the riders, all of whom were Belgian, on the main valley roads from north to south, via Angleur, Esneux, Aywaille, Barvaux, Hotton, Marche, Bande, Champlon and on to the checkpoint at a hotel in Bastogne, from where they returned to Lige by the same route.