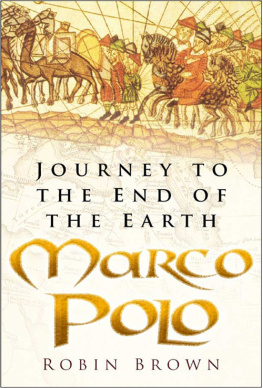

The Incredible Journey

R OBIN B ROWN

Foreword by Jeremy Catto

First published in 2005

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL 5 2 QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

Robin Brown, 2005, 2011

The right of Robin Brown, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7230 0

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7229 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

C ONTENTS

FOREWORD

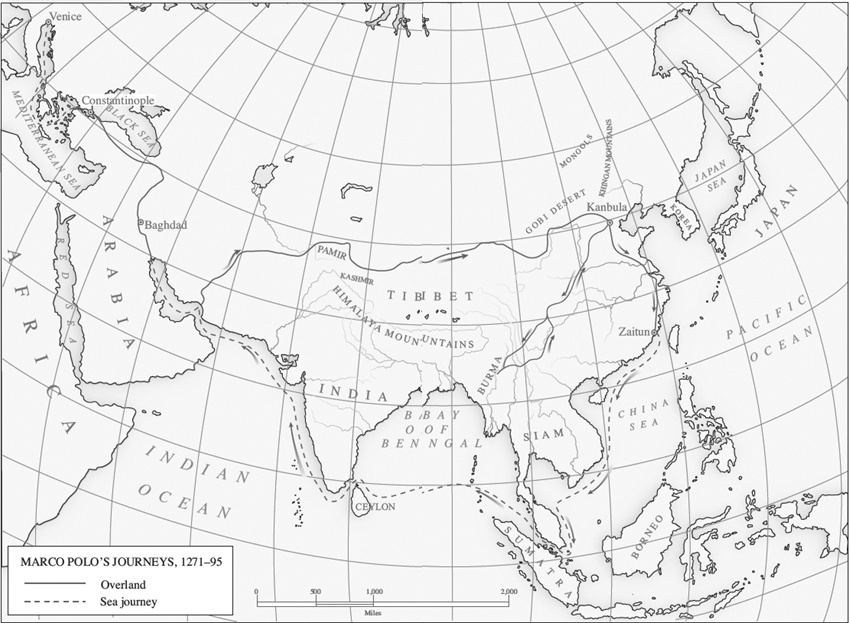

A fter two centuries of strenuous exploration and a landing on the moon, we are all familiar with incredible journeys. Even in the remote past, the capacity of humans to accomplish immense distances by land or sea never fails to surprise. In the century of Marco Polo the Mongols, nomads of the northern steppes, exemplified this in a dramatic though not unprecedented manner by sweeping through the settled lands to the south of them in large numbers, and demonstrating that they could reach from China at one end of the Eurasian landmass to Central Europe almost at the other in the course of a single season. In comparison the snail-like progress of the Polo family from Venice to the Mongol capital of Khan-Balik (Beijing), taking years to get there, seems much less impressive. But in another sense their journeys (for taken together there were several) can properly be described as incredible. For one thing, not everybody believed them. They were written up by an author of romances, Rustichello of Pisa, who claimed to have been told the story in a Genoese prison, and they circulated as an item in the well-known genre of the prose romance, like the entirely fictional Travels of Sir John Mandeville. Rustichello certainly gave the book its entrancing quality as a story, and it may owe some of the literally unbelievable details to his literary invention. Contemporaries treated it as a story, at best suspending their disbelief. Many later and more literal-minded critics have dismissed the whole of it as a literary forgery on much less substantial grounds, for instance for such negative reasons as the lack of any reference to the Great Wall of China; they have forgotten that in the Mongol Empire of Kublai Khan the Wall was a meaningless internal border and was probably ruinous for long stretches. The Travels of Marco Polo were not a guidebook to China, but a literary confection, an artful story. They can only be appreciated as a master-piece of Rustichellos marvellous story-telling genius.

Nevertheless, there is overwhelming evidence from independent Chinese and other sources that (and this is the other, more popular sense in which the journeys are incredible) both the main structure of Marco Polos travels and a surprising amount of the detail are authentic. The court of the Khan, the organisation of the Mongol Empire, the important role within it of indigenous Christian priests of the Nestorian church and many other features of the Central Asian world as he described them are confirmed by the reports of the Christian missionaries and envoys (Marco himself, in a sense, among them) sent by the Roman curia to the terrifying but hope-engendering new rulers of the East. He was neither the first nor the last of the series of travellers, from Giovanni di Piano Carpini between 1245 and 1248 to Guillaume du Pr in 1365, who sought to use the Mongol power to defend and enhance Latin Christendom. But the confirmatory evidence from China is even more impressive. Marcos description of the Imperial Palace at Khan-Balik is authenticated by the lineaments of the surviving Forbidden City. His account of the cities of Kinsai (Hangzhou) and Zaiton (perhaps Quanzhou) with its abundant commerce on the China Sea accord with contemporary Chinese descriptions. There is so much detail of trading and manufacturing activity, both in China and in Central Asia, that we must suspect Rustichello of using some lost relazione or commercial report written by Marco for the use of Venetian merchants in which case the statement that he heard the story from Marcos own lips in a Genoese prison must be a literary device.

One of the notable features of the Travels is its account of exotic animals and plants unknown in Europe. Marco Polo was careful to record them both as sources of wealth and objects of trade, and as dangerous beasts of prey the horses, falcons and sheep of Central Asia, the white horses of Mongolia, the Mongols sables and other furs, the musk deer of Tibet, the snakes of Kara-jang, the featherless and furry hens of Kien-ning-fu, the rhinoceros (or unicorns) of Sumatra, the tarantulas of south India, the elephants and unique birds of Madagascar and many others. Previous accounts of the travels have not given them much attention; now, at last, Robin Brown, a noted naturalist and maker of nature films, has taken proper account of Marcos observations. This is a very welcome addition to the considerable but patchy literature devoted to the Travels of Marco Polo.

Jeremy Catto

Oriel College, Oxford

General Introduction

M ARCO M ILLIONE

T he truly incredible story of Marco Polos journey to the ends of the earth, the book that earned him the title the Father of Geography, has for the last seven hundred years been bedevilled by doubts as to its authenticity. How much of his tale is a factual record, how much hearsay, and how much the best that Marco, bored with incarceration in a Genoan gaol, could recollect or indeed imagine? Did this intrepid Venetian actually trek across Asia Minor, explore the length and breadth of China as the roving ambassador of Kublai Khan, the most ruthless dictator in history? Did he really make his escape from almost certain death at the hands of Kublais successors by directing the construction of fourteen huge wooden ships in which he delivered Kublais relative, a beautiful princess, as bride to the Caliph of Baghdad after a voyage halfway round the world and so fraught with danger that it resulted in the death of 600 members of his crew?

Marco claims to have survived Mongol wars, hostile Tartar tribes, insurrections, blizzards, floods, the freezing cold of the worlds highest mountain plateaux and the scorching heat of its most arid deserts. Indubitably it was he who wrote the very first descriptions of real dragons (Indian crocodiles) and huge, striped lions (tigers) that swam into rivers to prey on men in boats, horned, armoured monsters (rhinoceros), armies of elephants with castles of archers on their backs, of a bird with feathers nine feet long (the great auk); of the salamander; and of cloth that would not burn (asbestos) and black rocks that burned like wood (coal). For good measure he claimed that the currency used in this mysterious Orient where the cities were larger than any in the West and a rich trade was to be had in glorious silks, cloth of gold, pearls, silver, gold, Arabian horses, ceramics, spices and exotic woods was paper! And in passing he introduced his native Italians to ice cream (frozen creams) and, yes, pasta (noodles) from his observations of Chinese cuisine.