Polly Evans is very cowardly and not at all fond of danger. She does, however, have an unfortunate tendency to seek out discomfort and sometimes even downright pain. It was this ugly trait that led her to throw in her comfortable office jobcomplete with its swivelly chair and free use of the coffee machineand take off on a leg-battering bicycle tour of Spain.

The result of her endeavors was one very sore set of limbs and her first book, It's Not About the Tapas. Polly indulged in further escapades the following year, this time swapping pedal power for a motorcycle to travel around New Zealand and write her second book, Kiwis Might Fly. Polly's third book, Fried Eggs with Chopsticks, tells the story of her sometimes- desperate battle to tour China by public transportation, while her fourth, On a Hoof and a Prayer, sees her learning to ride horses in Argentina. All of Polly's books are available from Delta.

Polly is also an award-winning journalist. When she's not on the road, she lives in London. Visit Polly's Web site for photos of her trips:

www.pollyevans.com

Also by Polly Evans

It's Not About the Tapas

Fried Eggs with Chopsticks

Kiwis Might Fly

On a Hoof and a Prayer

Published by Delta

For Thomas, Jake, Tilly, and Gabriella

Some say God was tired when He made it;

Some say it's a fine land to shun;

Maybe; but there's some as would trade it

For no land on earthand I'm one.

Robert Service, from The Spell of the Yukon

one

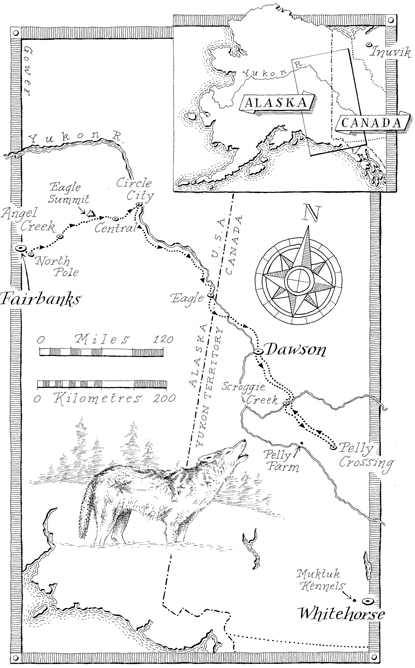

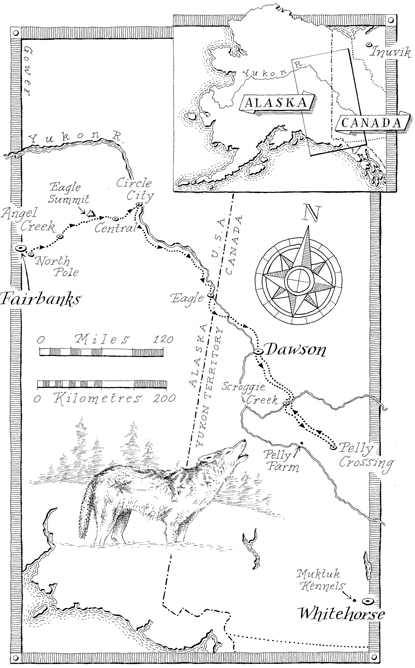

I flew out on Friday, January 13, and returned home on April 1. The dates had almost selected themselves, but they seemed curiously appropriate, for I feared I was embarking on a fool's errand. I was going to spend eleven weeks, in the heart of winter, in one of the most inhospitable climates on earth. The Yukon is a triangular-shaped territory in the far northwest of Canada. It borders Alaska to the west; at its northern tip lie the icy waters of the Beaufort Sea. Other people travel to the Yukon in the summer, when they can enjoy the long, balmy days that blend one into another with little darkness between. In September, though, the tourists pack their bags and leave. The attractions close. The museums doors are bolted and the buses are laid up until May. Even most Canadian people, who so proudly extol their pitiless winters when basking comfortably in the sun elsewhere, shiver at the thought of coming this far north during the frozen months. The average temperature in the Yukon in January is minus 15 degrees Fahrenheit, but the mercury can plunge much lower. Temperatures dip regularly into the minus forties; once, they dived to minus 81.

I flew out on Friday, January 13, and returned home on April 1. The dates had almost selected themselves, but they seemed curiously appropriate, for I feared I was embarking on a fool's errand. I was going to spend eleven weeks, in the heart of winter, in one of the most inhospitable climates on earth. The Yukon is a triangular-shaped territory in the far northwest of Canada. It borders Alaska to the west; at its northern tip lie the icy waters of the Beaufort Sea. Other people travel to the Yukon in the summer, when they can enjoy the long, balmy days that blend one into another with little darkness between. In September, though, the tourists pack their bags and leave. The attractions close. The museums doors are bolted and the buses are laid up until May. Even most Canadian people, who so proudly extol their pitiless winters when basking comfortably in the sun elsewhere, shiver at the thought of coming this far north during the frozen months. The average temperature in the Yukon in January is minus 15 degrees Fahrenheit, but the mercury can plunge much lower. Temperatures dip regularly into the minus forties; once, they dived to minus 81.

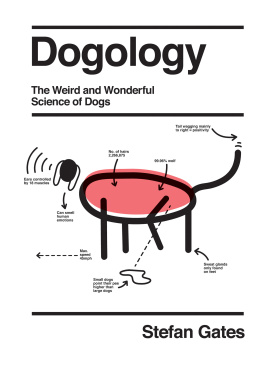

But there's another side to winter in this harsh land. As the nights grow longer, the milky jade and blood red of the northern lights weave across the skies. The snowshoe rabbits coats turn spotless white, and the Arctic foxes wear plush, dramatic furs. Winter has late blue dawns and the warm buttery light of the low midday sun. It has the jagged gems of hoarfrost and soft, feathery snow. Winter is the season of solitude and pure, glorious silence. And in winter, the sled dogs run.

It was the dogs that drew me. During my time in the north I'd be based at Muktuk Kennels, the operation of one of Canada's most famous mushers, Frank Turner, and his wife, Anne. I'd scoop poop, help with feeding, and learn to drive a sled. From Muktuk, I'd make further trips around the region. I'd follow the Yukon Questa thousand-mile dogsled race that runs between Fairbanks, Alaska, and Whitehorse, the capital of the Yukon Territory. I'd visit Dawson City, the town that sprang up in response to the frenzied Klondike gold rush. I'd fly to the very far north, to the Arctic Ocean itself. And through it all, I'd learn all I could about the howling, capering, tail-wagging world of sled dogs.

A short, stocky man with a salt-and-pepper beard and a well-worn red parka pushed through the swing doors of Whitehorse's airport, a tiny one-gate place where arrivals and departures were not just in the same building; they were in the same room. I recognized his face from his website photographs.

Frank? I asked.

You're Polly?

At this time, in January 2006, Frank Turner was the only person to have competed in each of the twenty-two Yukon Quest dogsledding races since the event's inception in 1984. Frank won the race in 1995 and still held the record for the fastest time. This year, Frankwho, in his late fifties, was wondering if he might be getting a little old for that kind of adventurewould not be entering the race, but his twenty-five-year-old son, Saul, would be running a team.

There was no call for feats of cold-weather endurance on that first night, though: Frank had parked his truck conveniently close to the airport's door, and we ventured just a few steps through the cold night air. In any case, the evening was warm by the Yukon's standards, a mere nine degrees, according to the pilot on the plane. I'd been concerned about what I should wear on the journey: Would I need my long woolen underwear to walk from the airport door to the car? But might I then overheat on the plane? In the end I'd put on ordinary jeans and sneakers, the car was near, and I was fine.

We drove out of town and onto the Alaska Highway toward Muktuk.

Saul's baby was born on Wednesday, Frank announced as we sped through the darkness. She's called Myla. She's beautiful.

Conversation moved on to the construction of the road.

The Alaska Highway was originally built during the Second World War, Frank explained. Alaska was considered by the U.S. military to be vulnerable to Japanese invasion: The Japanese wanted to control the shipping lanes in the northern Pacific, and the attack on Pearl Harbor had crippled the Navy's Pacific fleet. In response to this threat, the Americans set up a defensive line of airfields along the Alaskan coast, and this road, running 1,550 miles from British Columbia to Fairbanks, Alaska, was built to supply them.

The Japanese wanted to bomb the highway, as it was a major supply route, so they built it like this. Frank took one hand from the steering wheel and snaked it into violent meanderings. That way they couldn't take out whole sections of the road at once. And then the war ended, and they spent the next sixty years and goodness knows how many millions of dollars straightening it out.

About twenty minutes later, we turned off the main road and wound down a steep, snowy back road that had known little attention beyond the ministry of Frank's snowplow.

This is all First Nations land. Frank gestured toward the woods that surrounded us. Frank and Anne's hundred-acre ranch lay just below where we were now, on the banks of the Takhini River. They had bought the plot just six years previously.

I flew out on Friday, January 13, and returned home on April 1. The dates had almost selected themselves, but they seemed curiously appropriate, for I feared I was embarking on a fool's errand. I was going to spend eleven weeks, in the heart of winter, in one of the most inhospitable climates on earth. The Yukon is a triangular-shaped territory in the far northwest of Canada. It borders Alaska to the west; at its northern tip lie the icy waters of the Beaufort Sea. Other people travel to the Yukon in the summer, when they can enjoy the long, balmy days that blend one into another with little darkness between. In September, though, the tourists pack their bags and leave. The attractions close. The museums doors are bolted and the buses are laid up until May. Even most Canadian people, who so proudly extol their pitiless winters when basking comfortably in the sun elsewhere, shiver at the thought of coming this far north during the frozen months. The average temperature in the Yukon in January is minus 15 degrees Fahrenheit, but the mercury can plunge much lower. Temperatures dip regularly into the minus forties; once, they dived to minus 81.

I flew out on Friday, January 13, and returned home on April 1. The dates had almost selected themselves, but they seemed curiously appropriate, for I feared I was embarking on a fool's errand. I was going to spend eleven weeks, in the heart of winter, in one of the most inhospitable climates on earth. The Yukon is a triangular-shaped territory in the far northwest of Canada. It borders Alaska to the west; at its northern tip lie the icy waters of the Beaufort Sea. Other people travel to the Yukon in the summer, when they can enjoy the long, balmy days that blend one into another with little darkness between. In September, though, the tourists pack their bags and leave. The attractions close. The museums doors are bolted and the buses are laid up until May. Even most Canadian people, who so proudly extol their pitiless winters when basking comfortably in the sun elsewhere, shiver at the thought of coming this far north during the frozen months. The average temperature in the Yukon in January is minus 15 degrees Fahrenheit, but the mercury can plunge much lower. Temperatures dip regularly into the minus forties; once, they dived to minus 81.