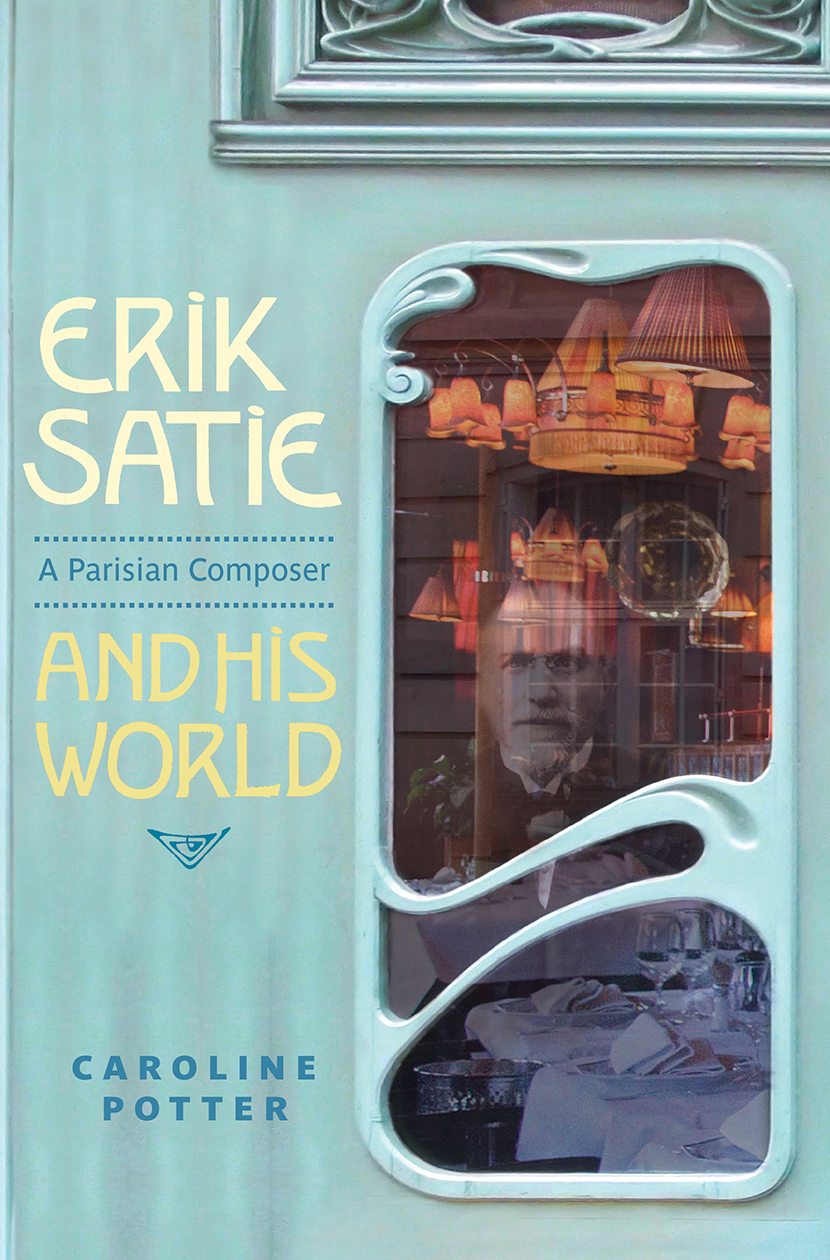

Erik Satie

A Parisian Composer and his World

This brilliant and accessible new study of Satie gets right inside his contemporary Parisian world, relating its complex and fast-changing artistic climate to scientific and social issues, and most importantly to mechanical and street music. Dr Potters painstaking and wide research brings many new discoveries too, and leaves us with a clearer vision of what the enigmatic Satie was really about. Emeritus Professor Robert Orledge, University of Liverpool.

Erik Saties (1866-1925) music appeals to wide audiences and has influenced both experimental artists and pop musicians. Little about Satie was conventional, and he resists classification under easy headings such as classical music. Instead of pursuing the path of a professional composer, Satie initially earned a living as a caf pianist and moved in bohemian circles which prized satire, popular culture and experiment. Small wonder that his music is fundamentally new in conception. It is music which is not always designed to be listened to attentively: music which can be machine-like but is to be played by humans. For Satie, music was part of a wider concept of artistic creation, as evidenced by his collaborations with leading avant-garde artists and in works which cross traditional genre boundaries such as his texted piano pieces. His music was created in some of the most exciting and creatively stimulating environments of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century: Montmartre and Montparnasse. Paris was the artistic centre of Europe, and Satie was a notorious figure whose music and ideas are inextricably linked with the City of Light. This book situates Saties work within the context and sonic environment of contemporary Paris. It shows that the influence of street music, musicians and poets interested in new technology, contemporary innovations and radical politics are all crucial to an understanding of Satie. Music from the ever-popular Gymnopdies to newly discovered works are discussed, and an online supplement features rare pieces recorded especially for the book.

CAROLINE POTTER is Reader in Music at Kingston University London. A graduate in both French and Music, she has published widely on French music since Debussy and was Series Advisor to the Philharmonia Orchestras Paris 2014-15 season.

To Paul, with love

Contents

Illustrations

Music Examples

Preface

E RIK Satie is known to audiences around the world as the composer of three Gymnopdies (1888), piano pieces which are more popular than any others of his place and time, the Paris of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He has always been a crossover composer who appeals well beyond classical music audiences. But Satie is more than a composer of short, memorable and technically unchallenging piano pieces. He was also embedded in the social milieu and artistic environment of Paris and he collaborated with some of the best-known artists and writers of his day. A highly experimental artist and a radical in both art and politics, he often concealed his views behind an ironic or jokey surface. This book situates Satie firmly in the Paris of his time and focuses both on well-known pieces and works which are barely known at all. Some of these rare pieces are available as recordings that accompany this book.

Satie witnessed cataclysmic change in his lifetime. From abject defeat in the Franco-Prussian war of 18701, France re-emerged as one of the most dynamic, innovative and artistically vibrant countries in Europe. Sound recording was a concept dreamed up by the Montmartre poet and amateur scientist Charles Cros, though Thomas Edison patented the phonograph and was the toast of the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Street lighting by electric arcs coexisted with gaslight by the turn of the century and eventually superseded gas; Paris nickname the City of Light might have originally derived from its status at the centre of the Enlightenment, but the nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw it take a literal turn. The telephone was introduced to France in 1879 and the first transatlantic calls were made from Arlington, Virginia to Paris in October 1915. In 1892, Lon Bouly patented the film camera ( cinmatographe ), though the Lumire brothers were the first to exploit the new invention. And the Paris Mtro opened in July 1900, during the other major Exposition Universelle in the city during Saties lifetime. While he was not always an active or willing participant in these changes for instance, Satie hated the telephone, preferring the beautifully calligraphed written word the Paris he knew as a child was transformed by developments in communications, technology, transport and society. He first moved to Paris as a four-year-old in 1870: his father, Alfred, sold his shipbroking business on his return from active service in the Franco-Prussian War and was offered a job as a translator in Paris thanks to his friend, the historian Albert Sorel. But following the death of Saties mother in 1872, the future composer and his brother Conrad were sent back to Honfleur to live with relatives until their grandmothers death in a drowning accident in 1878, when they returned to Paris.

Little about Erik Satie was conventional (not least the spelling of his first name, which he changed as an adult), and he resists classification under easy headings such as classical music. He studied at the Paris Conservatoire, though was dismissed without obtaining a diploma, and at the time of the Gymnopdies he was working sporadically as a pianist in the cafs and cabarets of Montmartre, accompanying singers and shadow plays and performing in the background to everyday activity. Understanding these popular roots is key to understanding Saties music.

La musique des pauvres music of poor people is an expression that crops up time and again in French literature and the journalism of Saties lifetime, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. La musique des pauvres was synonymous with music played on the barrel organ: music which was free (unless the listener deigned to give their spare change to the performer) and played on the street by tramps or ex-servicemen scraping a living by turning the handle of a hired instrument. The Parisian barrel organ grinder was therefore a marginal figure, and as such he was an inspiration for poets and artists who wished to express sympathy with people outside the bourgeois norm. Saties music is often short but repetitive, simple in texture and harmony and sometimes based on popular tunes all characteristics shared with barrel organ music. It is irresistible to place Satie, often described by his Montmartre acquaintances as Monsieur le Pauvre, in this sonic landscape.

The many technological innovations in the Belle Epoque were coupled with an artistic interest in machines as one aspect of the self-conscious modernity of the period. Beyond the Belle Epoque, the rapid pace of technological change was mirrored in artistic enthusiasm which often surfaced as admiration for everything new coming out of the United States: praise for everything from the motorcar to skyscrapers was commonplace in art of the 1910s and 1920s. As a participant in both the cabaret music scene and in new artistic movements of the first decades of the twentieth century usually heralded by manifestos and small-circulation art magazines Satie was at the centre of this Parisian bohemian and avant-garde milieu.

Technological advances engendered fear as well as excitement. Satie much admired the artist Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, creator of many large-scale frescos including those in the Panthon; in 1889 Puvis was taken to the Galerie des Machines, one of the exhibits at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris. Maurice Raynal claims he never would have set foot there on his own and, on seeing the exhibits, he exclaimed: Oh! My children, there is no more art to be done! How could a painter, a poet, fight such social influence, such power over the imagination? Lets get out of here! What will become of us artists in the face of that invasion of engineers and mechanics? Saties attitude to innovation is far closer to Raynals than Puvis. The Exposition Universelle was the most prominent event in Paris in 1889: the Eiffel Tower served as the entrance arch for the exhibition, which was held on the Champ de Mars. While the impact on musicians of the colonial display part of the exhibition which included a Javanese gamelan and Annamite theatre is well known, that of the Galerie des Machines has been little explored. The Galerie des Machines, which was designed by the architect Ferdinand Dutert and the engineer Victor Contamin, was 111 metres long the longest interior space in the world at the time. It was reused in the 1900 Exposition Universelle and included a giant projection screen.