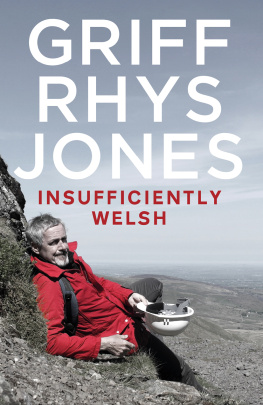

Mountain

Exploring Britains High Places

GRIFF RHYS JONES

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11, Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published 2007

Published in paperback in Penguin Classics 2008

1

Copyright Griff Rhys Jones, 2007

All rights reserved

The moral right of the editor has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject

to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent,

re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers

prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in

which it is published and without a similar condition including this

condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

978-0-14-191911-9

Contents

Introduction

I was actually at a meeting to talk about something else entirely when somebody suggested that I could present a programme about mountains for the BBC.

But I know nothing about mountains, I bleated.

Thats excellent, the executive replied. It will be a new experience for you.

But isnt there a certain amount of skill involved?

Well, we can see you mastering those.

And if I dont master them?

Thats good television.

So I was recruited, or press-ganged even. This is the story of that trip, which took up a lot of 2006, but it is obviously not a mountaineers account. I was a virgin climber and a trembling one. I had once crawled up the volcano Stromboli hoping to dodge fridge-sized rocks. I had been skiing in various parts of Switzerland. I had even crossed the High Atlas in a Fiat Punto. I thought I knew what a mountain was like. I was wrong. Now I have climbed fifteen British mountains, some of them three or four times in a row for the cameras. I have scrambled, bouldered and scaled. By climbers standards, of course, I have done nothing, but I do feel, well experienced.

As a virgin, I was a little sceptical to begin with. Was the discomfort going to be worth the effort? Apart from a little panting, could it really make a man of me? Was I really going to walk down my flat city streets with a new glint in my eye and a swagger in my step? You can judge for yourself. There were some minor physical challenges, to which I usually failed to rise, and a smattering of minor orgasmic summiteering moments. But what began to fascinate me as an outsider was the history of the vertical world I encountered. By walking into the hills I discovered that mountains are a separate environment, a different territory with their own rules, where for thousands of years people have lived, but with difficulty, where bad men have fled, where dreamers have escaped, where ordinary people have struggled to survive and where elements of everyday existence long since abandoned on the easy flat lands have hung on right up to the present age. And on every climb there came a moment when we crossed a stile or climbed a wet gully or breasted a ridge when we suddenly broke through into an undisturbed, wild place, bare, open, ravaged by previous ice ages and largely left to itself: a real wilderness on an overcrowded island.

Almost a third of our country is covered in mountains. This is a minor introduction to some of the people who have been there and lived there. It would have astonished Mr Tarrant in the fifth form but I did become fascinated by the way that geography can affect our lives and shape our history. British hills hatched rebellions, attracted speculators, sheltered eccentrics, powered industry and prompted scientific investigation. So there is a little bit of that sort of stuff here, in among the subjective whimpers and triumphs.

Of course I didnt go on my own. Cubby, Mark, Fraser and other experts were with me all the time. They not only showed me the ropes, lovely purple ones too, but listened to my wild prattling and suffered my prickly inexperience. There were cameramen and assistant producers and directors too who struggled up slopes and sheltered in wet hotels. They are largely hidden in this account, as they were in the resulting series. But one thing rather frightened me, a portent of the new media reality, I suppose. In all our bold company I was definitely the oldest person in the unit. Are you all right, Griff? was too common an enquiry. Yes, thank you. Im only fifty-four, was a grumpy common response. It took my wife to point out to me that I was in fact only fifty-two. I couldnt really hide my inadequacy behind pretend advanced old age. Damn.

But at the end of months of trudging and exploring, climbing and clambering, I have to admit that this fifty-two-year-old virgin was left with one inescapable question. What took me so long? The hills were an extraordinary and unexpected experience and as I sit here writing this I find I am hankering to go back. I hope, when you read this account, you will be able to see why.

1. North-West Scotland

Crouched in a Cessna at ten thousand feet I could finally understand why blokes with preposterous facial hair called aircraft crates. The doors were aluminium straws with a shell of silver paper. If I leaned too hard against the side I was going to leave my own shape pressed in the frame. The entire plane seemed to bend and crumple as we flipped around like a paper bag in a wind tunnel.

My pilots company was running out of Loch Lomond. Were going to take tourists, fishermen and landowners out to the furthest isles, he shouted over the roar. Now he was taking me by the quickest route to the far north west of Britain.

As we crawled around massive lumps of hill and thundered laboriously along valleys neutralized with snow, I dimly realized that that thin cotton thread of a line across the bottom was the main road between Altnaharra and Inverness. On the map there was satisfying emptiness, and emptiness in our crowded island is rare, except that and I apologize if this seems blunderingly obvious it wasnt empty. The space was filled by mountains an upthrusting territory that needed endurance to cross. True, the airplane could curve effortlessly around that beetling cliff. A car, with its powerful built-in laziness, could slip straight up hills and down the other side. But the road followed the line of least resistance and added miles to a journey, snaking round the low route, avoiding heavy, difficult climbs. These ranges I was flying through were in truth just as inhospitable as those mid-European Alps I had crossed so many times by giant jet-liner.