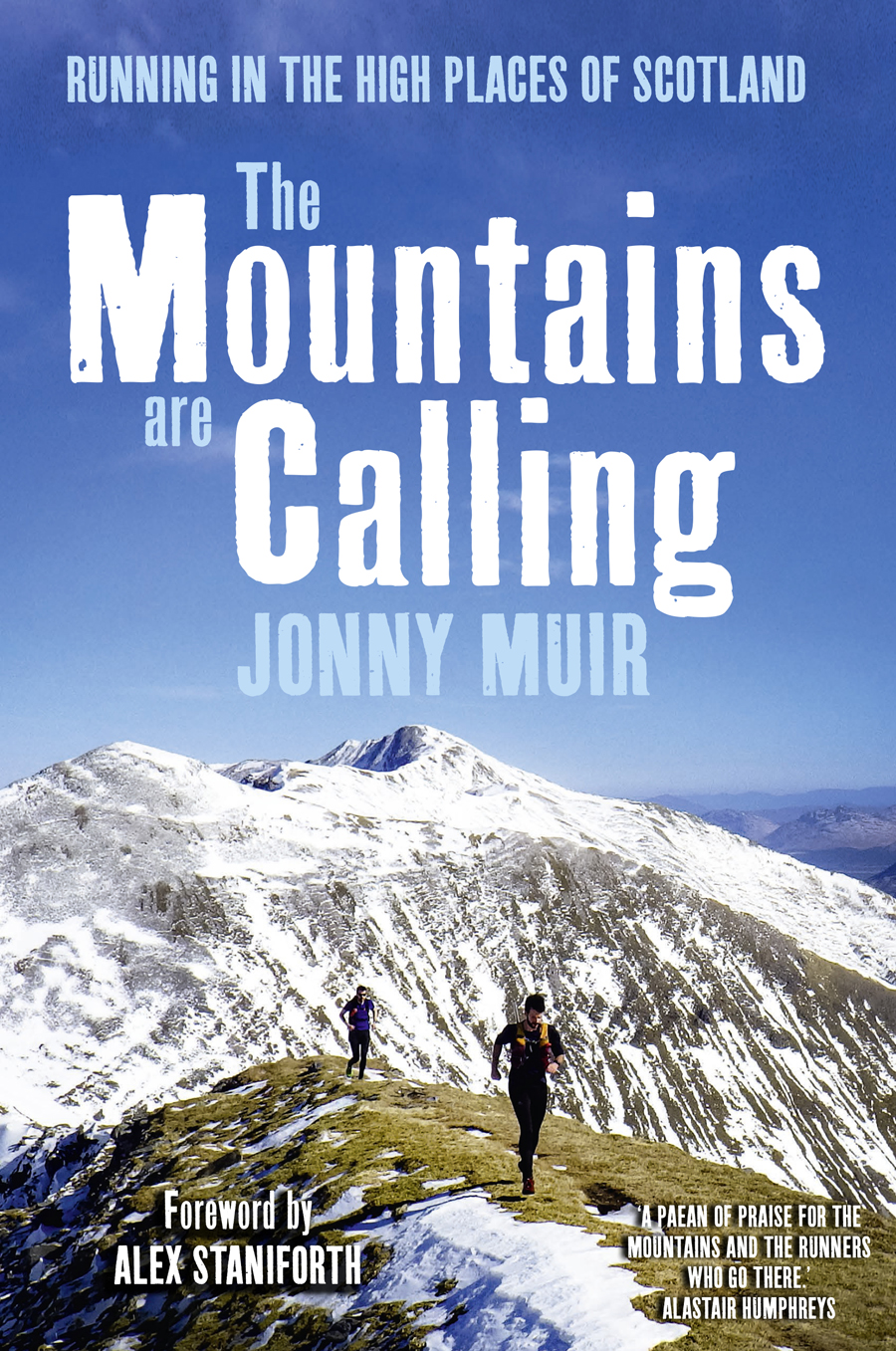

My first calling to Scotland was fairly unextraordinary. An impressionable child from Cheshire, I craned my neck at mountains like nothing I had seen before. From Loch Lomond to Fort William I pointed at these rocky shoulders with wide-eyed enthusiasm; asking whether they could be Ben Nevis, the mountain that had captured my imagination. Not much later, the nature of Scotland became etched in my memory after being almost snowed in as we crossed Rannoch Moor. This was not even in midwinter, but in March. A decade later, Scotland would call me back as the training camp for my Himalayan expeditions. As the old expression goes: Everest is great training for the Scottish winter!

Anyone reading this book will have their own Everest their ultimate goal in life. Mine would be climbing the mountain itself, which I have attempted twice.

I can relate to the occasion in Glen Coe, when Jonny Muir lost his romantic view of running mountains. Similarly, I lost my calling to climb. Although I grew to hate the expression, its true that the mountain will always be there. For a while, Everest would remain an unanswered voicemail.

This realisation prompted me to seek a challenge closer to home, and it was while planning to link the highest points of all the United Kingdom counties, by cycling, running, walking and kayaking, that I discovered this amazing athlete and writer. My 5,000 mile journey, titled Climb The UK, was completed in July 2017, and he was the only person to have made an attempt before me.

In a world with so little uncharted and records set so high, its thrilling to devise unique ideas that dont involve a chicken costume, and somehow reassuring to discover it has already been done by such a remarkable individual. Without a precedent it would be too easy to dismiss the idea as absurd and probably unachievable. Standing, exhausted, on Moel Famau, my final county top, I felt I had done well, but proof came when I was invited by my exemplar to write the foreword for the exceptional piece of writing that follows: The Mountains are Calling .

On four expeditions to the Himalayas, I have experienced altitude sickness, sleepless nights under the steam of breath, and 20 temperatures that left icicles in the stubble of my older colleagues, but it is still not an environment as unpredictable, characterbuilding and enchanting as that of Scotland, whose bipolar tendencies can hit before the clouds roll off the hills. In contrast, the monsoon jetstream that knocks each Everest season on the head is forecast almost to the day. Predictable or otherwise, and be it Everest or Scotlands revered Chno Dearg, these mountains crush dreams without apology and can strike fear into the most robust of hearts.

On Ben More Assynt, to catch up on time, I was obliged to hop over boulders and run towards Conival, sliding down scree before reaching Inchnadamph. Like Jonny I received disapproving looks from hillwalkers who champion the slower approach, but I had sixty miles still to cycle and would have to be in the saddle before they reached the summit. At other times, running became a means of selfpreservation; to generate heat, or simply to get me off the mountain before wind and rain could finish me off. I discovered how, in the space of a week, Scotland could add the danger of heatstroke to that of hypothermia; happily running through snow on Ben Macdui, sunburning in the Arrochar Alps.

Shivering in a phonebox at Braemore, south of Ullapool, I took comfort in knowing that someone special had been here before me, when a ninetymile day turned into an infuriating battle against headwinds, and the glens and blotted moorland, the chilly swathes of pine forest, had merged into one.

Arduous days of Himalayan climbing can start early in alpenglow, piercing blue skies. You can travel slowly, and finish early when the climbing day is short, with Sherpa hospitality and a mug of hot tea waiting. There was no hot tea in Glen Affric when I was benighted and deprived of a warm bed at the youth hostel, instead making an impromptu wild camp, scooping up dry protein powder with a toothbrush for dinner.

The tipping point came on Crn Eighe the next day, when isolation drove me to converse with the sheep, and rain penetrated every seam of my clothing. False summits and lost paths all got too much and, in a weak moment, I crumbled into childish sobbing. The weight of the mountain seemed to sit on my shoulders, laughing in a booming cackle of wind. There was no option but to get back up and push on, though I had run out of ways to say: that was the worst day of my life.

Whereas, a midge assault gave me good reason to run up Merrick with a fierce breeze tickling the hairs on my neck, and the sunset across Galloway cracking the sky into purple fire. Racing the daylight towards Durness, the otherworldly shadows of Assynt fell like dominoes behind me; the salty silence on the summit of Goatfell broken by the blast of ferry horns below; and the turquoise coasts of the Orkney Isles. In these moments the answer to the question why was easy: being in places I had never known existed; free to do my own thing and step above the clouds. To think hill running was banned in Scotland in 1850! Can you imagine the lynch mob of XTalons and hip belts if that happened today?

With the same passion and dedication he applies to his own training, Jonny Muir has gone the extra mile to gather a staggering wealth of insight. Reading about Finlay Wild in the Cuillin particularly fed my awe of the gnarly runners that Scotland has bred, whilst also sending shivers to my feet. It reminded me of a multiday hike of the Skye Trail two years earlier in penetrating coastal rain. Sopping wet and squelching into Portree, we were apprehended by burly Highland workmen: Aye, lads, did you forget to take yer tablets this morning?

These experiences raise our thresholds and make us more resilient to everyday life. Its hardly surprising that hill runners are so hard to break. We have a lot to thank these athletes for: superhuman feats that reset the bar and inspire apprentice runners. Its our whitehaired heroes that dare us to dream that, yes, we really could join their exclusive company. We are hungry to learn their art.