The Giving Tree

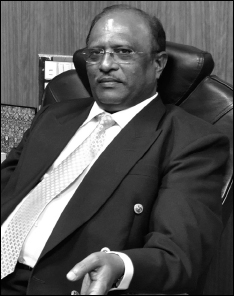

ASHOK KHADE AND I WERE in the middle of our conversation at his Navi Mumbai office, when he held up two pensone was a simple green pen and the other was a fancy Montblanc. These two fountain pens tell the story of his life. Ashok has owned the green pen for most of his life, ever since he bought it for Rs 3.50 thirty years ago. In 1973 when Ashok had to appear for his class eleven board exam, he didnt have even four annas to replace its nib. His teacher had to give him the money to have the nib changed so Ashok could take the exam. He wrote the exam with this pen as an aspiring youth looking forward to his destiny. The Montblanc penworth Rs 80,000is a symbol of his success.

Ashok Khade is now managing director of DAS Offshore Engineering Private Limited. In 201112, his company, which makes huge platforms used for extracting crude oil from the sea, filed a turnover of Rs 140 crore. DAS Offshore employs 400 people and has carried out the fabrication of the D.Y. Patil Stadium in Navi Mumbai, where matches of crickets Indian Premier League are held. The skywalks built for crossing the road at Mumbais Bandra, Sion and Ghatkopar areas were put up by Ashoks company in a matter of months. Even though he is a big businessman now, Ashok still keeps the green pen to remain groundedit is a constant reminder of his early life and where he comes from.

The Khade family has lived through extremely terrible times. They started out in Ped, a tiny village in west Maharashtra in the Tasgaon tehsil in Sangli district. The family did not earn very much. Ashoks father mended shoes near Chitra Talkies in Dadar, MumbaiAshok says that the tree under which his father sat and worked is still standing. His mother, Tanhu Bai, worked in the fields for twelve annas a day. Though it was tough to bring up six children on these meagre earnings, the parents sent the eldest son, Dattatreya, to a relatives house in Sholapur to study. Till then, Ashok had no idea just how poor they were. Hed send postcards to his father at the Chitra Talkies address, asking him for moneybut he never got a reply.

Then something happened which made Ashok realize how utterly poor his family was. And that was the day he made up his mind to rescue them from poverty. Ashok was in class five then. It was monsoon, and his mother had sent him to get atta (flour). On his way back, Ashok slipped and fell in the slush, and all the atta spilled. When he returned home empty-handed, his mother started crying as there was nothing to eat in the house, and she wondered how she would make bhakri (round, flat, unleavened bread, similar to chapatti) for the family. She brought some corn and black hulge (horse gram) from his classmate Savarde Patils house, and made bhakri from it to feed the children.

Everyone went off to sleep, but at four in the morning, Ashoks younger brother Suresh woke up feeling hungry. Their mother asked them to sleep and promised she would do something as soon as day broke. After an hour or so she made dough with some seeds and made bhakri with it and fed Suresh.

Eventually, the Khade family was able to fight poverty because they never compromised on the childrens education. Ashok studied in Ped village till class seven, then moved to Tasgaon to study till class eleven. He had somehow managed uninterrupted schooling till then, but 1972 proved to be the annus horribilis for all of Maharashtra. There was no rain and the state was gripped by the worst famine in the last 100 years. By October 1972 the situation became alarming. There was no drinking water and no food. Millet was imported from the United States to feed the people of Maharashtra. The government distributed sukhdirawa (semolina) mixed with gurto the masses. Close to 50 lakh people, i.e., 20 per cent of the rural population, worked under the employment guarantee scheme launched by the government. In a situation where even well-off farmers were reduced to hard labour, the Khade family could hardly remain unaffected.

The supply of grain was discontinued in Ashoks hostel and there was no food to be brought from home either. When Ashok went back to the village his father said, Son, Im not responsible for the famine. I cant be blamed for not being able to feed you bhakri. All the utensils in the house have been sold. But you dont give up. And then he repeated a Marathi proverb which translated to: till the time the palash trees have leaves, dont think of yourself as poor. The palash needs little water; its leaves are used to make dona pattal (disposable plates). Ashoks father told him that even if the situation is such that their family has to resort to selling their utensils, they could rely on the palash and eat off its leavesthey will not be poor as long as the palash tree is in bloom.

This experience gave Ashok the incentive to take life head-on. Luckily, Patils family took Ashok under their care and fed him for about six months. But food was not the only concern. When it was time for exams, Ashoks teacher Desai Sir noticed his torn shirt and trousers and bought him clothes. Wearing his new clothes Ashok took the exam and scored 59 per cent.

The next stop was Mumbai. Ashoks older brother Dattatreya had found a job in the shipyard of Mazagaon Dock as a welding apprenticethis spurred on Ashoks dream of becoming a doctor. He studied science in class eleven and was studying at Siddharth College; he would be eligible for admission to a medical college after class eleven. To prepare for the entrance exam he joined the well-known Bholas Classes in Dadar. Though Ashok was supported by his brother he also earned Rs 70 a month giving private tuition; but suddenly, the tide turned once again when his brother said that he could no longer bear his expenses.

Perforce, in 1975, to support the family, Ashok had to give up his dream of becoming a doctor and start working as a welding apprentice at Rs 90 per month at Mazagaon Dock. To date, Ashok has not been able to forget that twenty-six of his classmates went on to become doctorsincluding some less proficient at academics than him. These classmates were now studying medicine at Mumbais J.J. College and K.E.M. College, while just a few kilometres away Ashok was being trained to make ships.