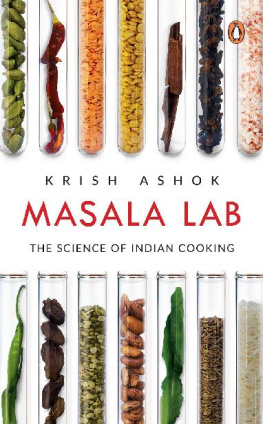

KRISH ASHOK

MASALA LAB

The Science of Indian Cooking

Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

MASALA LAB

Krish Ashok is not a chef but cooks daily. He is not a scientist, but he can explain science with easy-to-understand clarity. He trained to be an electronic engineer but is now a software engineer. He learnt to cook from the women in his family, who can make the perfectly fluffy idli without lecturing people on lactobacilli and pH levels. He likes the scientific method not because it offers him the ability to bully people with knowledge, but because it confidently lets him say, I dont know, let me test it for myself. When he is not cooking, hes usually playing subversive music on the violin or cello.

He lives in Chennai with his wife, who sagely prevents him from buying more gadgets for the kitchen, and his son, who has the flora and fauna in the neighbourhood terrorized.

You can follow him at @krishashok on Twitter at your own risk.

To Sonu,

who makes amazing rasam without any science

B efore I left for my first trip abroad, I asked my late maternal grandmother, who was a fantastic cook, to tell me the recipe for adai, a crispy multi-lentil pancake that is very easy to make but hard to get right. I probed her about ratios, texture, timing and sequence. Clearly, she was not used to being asked these questions. Cooking for her came from aromas, the tactile memory of her fingers, and the visual and auditory cues. Once I was done with my interrogation, she asked me to show her what I had written. She said, You missed one ingredient. Write it down.

I looked at her, pen in hand, waiting.

Patience. Thats the ingredient you are missing. If you give anything enough time, it will turn out delicious. You can approximate all the other ingredients.

Introduction

Cooking, people will tell you, is an art. Indian cooking, in particular, is supposed to be an art wrapped in oriental mystique, soaked in exotic history and deep-fried in tradition and culture. Western food is supposed to be scientific and bland, while Indian cooking, we are told, is all about tradition and flavour. Some people innately have a knack for it, and many dont. The Tamil expression kai manam , which literally means hand flavour, is used as a compliment for those who have somehow had this arcane knowledge handed down to them. The metaphor also hints at where exactly that knowledge is stored (hint: not the brain) and, thus, is hard to transfer to another person.

The Covid-19 pandemic transformed life as we knew it. The fact that cooking is an essential life skill stares us more intensely in the eye than at any time so far. But learning to cook Indian food, it turns out, is a byzantine maze with conflicting instructions and pseudoscience. The convenience of being able to Swiggy some amazing butter chicken from a dhaba 5 km away, and the fact that more and more young people are living by themselves in cities, which are not their home towns, means that even if they want to cook, they neither have the time nor the daily access to someone who can mentor them in the way your grandmother learnt to cook, from an older member in her family. And because we have never bothered to build a standard, documented model of underlying cooking methods and the science behind those techniques, a metamodel, if you will, Indian cooking continues to wrongly be considered all art and no craft.

This is a pity, given that this part of the world has contributed traditional culinary methods the scientific West has embraced as new-age food science in recent years. The curcumin in turmeric is now a superfood, as is the drumstick, which is sold as moringa powder in Brooklyn for an arm and a leg. Fermentation and sprouting of legumes go back thousands of years in India, while pickling as a technique to extend the shelf life of food in a hot and unforgiving climate has been around forever. There is no dearth of hey-look-our-ancient-tradition-is-now-science chest-thumping on social media, but what is missing is any serious attempt at actually documenting these culinary practices as part of a practical engineering playbook, outside of the cultural, historical and spiritual contexts.

By treating our culinary tradition as something sacred, artistic and borderline spiritual, we are doing it a grave disservice. Let me take music as a metaphor here. Indian classical music, one of the most sophisticated artistic traditions in the world, has, I would argue, suffered from the lack of documentation and archiving. In fact, the insistence on purely oral traditions of transmission of knowledge have ended up making the art a very elitist affair not accessible to the wider population. Western music, in contrast, has a simple, visual system of notation that is able to accurately capture every nuance. Because of this, we are able to perform a Bach concerto in exactly the same way as he intended in the eighteenth century. As an amateur musician myself, my teachers would often tell me that Indian classical music cannot be described and documented because its nuances are beyond the ability of language to describe it with fidelity. With due respect, I think thats bullshit. What we are doing with food is rather similar. By not using the tools and language of modern science and engineering to continuously analyse and document different Indian culinary traditions, and instead just writing down recipes, we are doing the food equivalent of lip-syncing to a pre-recorded track.

Food, even sun-blushed, Himalayan pink salt-tossed palak chaat, drizzled with organic, hand-blended coriander pesto, is ultimately chemistry. Its not always simple chemistry, Ill give you that, but then again, the physics of how the global positioning system (GPS) works on your smartphone involves Einsteins general theory of relativity, something that most Silicon Valley software nerds who build these apps dont understand entirely. I want to make a strong case for understanding basic food science, minus the chemistry equations and dry academic white papers on the correlation of temperature and water absorption levels in chickpeas (chickpeas soaked in warm water absorb it faster, a trick you can use in case you forgot to soak them overnight). Cooking is essentially chemical engineering in a home laboratory, known as a kitchen, with an optional lab coat, known as an apron. Unfortunately, pseudoscience, amplified by WhatsApp, has given the word chemical a negative connotation. People regularly say, I dont want to eat anything that has chemicals in it. In that case, Id advise them to fast indefinitely. Its a cognitive fallacy, which assumes that somehow the glutamate salt in monosodium glutamate (MSG) is a chemical, while the same glutamates inside the fleshy part of a tomato are natural. At a molecular level, they are the same thing! But more on that in Chapter 5.

Understanding basic food science will make you a significantly better cook and also unlock your ability to experiment boldly without being tethered to recipes. Food science will also make for richer and more fascinating conversations with your grandmother when she teaches you how to make the perfect prawn theeyal. Knowing how pressure caramelization works, or rice to water absorption ratios, or the ability of glutamate molecules to add savouriness will help you imbibe her cooking methods and adapt it to many other dishes.

I can see why this sounds daunting, considering that we live in a world buried under the collective weight of flowery adjectives used in food literature in general. Tomatoes are either sun-blushed or French-kissed, the lowly black urad dal takes on a Silk Route ambience in the form of Bukhara or Samarkand, and spices are always exotic and recipes handed down over the ages. Indian food writing continues to romanticize desi cooking with the same orientalist tropes that look down on technology and promote an utterly fraudulent notion of natural and organic, continuing to perpetrate the silly idea that Indian cooking is not scientific and that those who are good cooks just know by shudh desi ghee instinct what to add, and how and when.

![Anita Jaisinghani - Masala: Recipes from India, the Land of Spices [A Cookbook]](/uploads/posts/book/320725/thumbs/anita-jaisinghani-masala-recipes-from-india-the.jpg)