Table of Contents

To

Amma

who has been the gentle

wind in our sails

Udharet-atmana-atmaanam na-atmaananam-avsaadyet

Aatmaiv hiyatmano bandhuraatmaiv ripuraatmanah

One should lift oneself by ones

own efforts and should not

degrade oneself; for ones own Self

is ones friend, and ones

own Self is ones enemy.

Bhagvadgita 6:5

Koi urooj de na zawaal de, mujhe sirf itna kamaal de

Mujhe apni raah mein daal de, ki zamaana meri misaal de

Teri rehmaton ka nuzool ho, mujhe mehnaton ka sila mile

Mujhe maalo-o-zar ki hawas nahin, mujhe bus tu rizq-e-halaal de

Mere zehn mein teri fikr ho, meri saans mein tera zikr ho

Tera khauf meri nijaat ho, sabhi khauf dil se nikaal de

Teri baargaah mei ae khuda meri roz-o-shab hai yahi dua

Tu rahim hai tu karim hai, mujhe mushkilon se nikaal de.

Do not grant me success or failure; grant me only this miracle

That I follow your path and be an example for mankind.

Shower me with your blessings; may my hard work be rewarded

I crave not for wealth, just grant me what is due to the honest

May you always dwell in my thoughts, may I feel you in my breath

May your fear be my freedom, may I be free of all fears

In your court Lord Almighty, from dawn to dusk I pray

You are merciful and generous, deliver me from my hardship.

Allama Iqbal (Sir Muhammad Iqbal)

CONTENTS

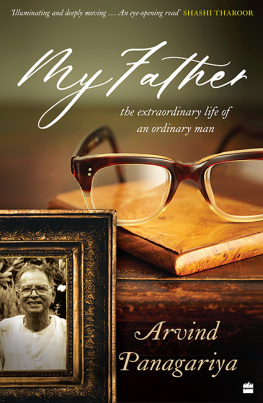

T ell me, Sir, in which field could I make a great career? the child asked.

The father replied: Be a good human being. There is a huge opportunity in this area and very little competition.

This book is the result of the personal experience of being a child of one such father. It is a biography of my genes. Seeing him live was like reading an uplifting story and reading his diary was a pilgrimage. Those are the sources of my work.

The diary begins with a quote from S. Radhakrishnan: Let no one look upon work as a burden. Good work is the secret that keeps life going. While one should not hanker after results, life without work would be unendurable.

That work which we fill our time with gives us reward, remuneration and restlessness. It produces conflict, it offers choices, it throws up challenges and produces many dilemmas.

Amid a dual quest for material prosperity and mental peace, what can provide an anchor to individuals and institutions? What can serve as a guide as we navigate through turbulent waters, both in personal and public life?

Every incident in the book is from real life and it powerfully underscores the role of core values in life. It is possible to prosper in the world, especially in a developing country, where there is a revolution of rising aspirations and cut-throat competition, and yet preserve ones principles. Paying the price for adhering to those principles might seem painful, but that is like the pain that a mother feels while bringing new life into the world. It is inescapable, it is joyous and it is the axis around which the world moves.

Honesty and truth are not merely ideals that remain elusive. They form the survival kit of many whose lives dont seem extraordinary because they are not popular. Their stories are not heard because they havent been written about. These are stories that represent an era, an entire generation. These stories are not over. Every generation will need these stories when it has exhausted its amoral quest of pure materialism or reached the apotheosis of its permissiveness and compromises.

These ordinary lives may not be well known or heroic in popular perception. In their own limited world and for those who come in contact with such men and women, such people are individuals who have lived life on their own terms. They have faced trials and tribulations, traumas and triumphs but remained afloat because they had a hard inner core. They may not be icons, recognized and idolized. Their life inspires because it is a vindication of certain lasting values that survive in every society. Such lives provide hope and keep us connected with the unseen forces that govern us.

There are many in every society who think with their heart and feel with their head. They keep working silently, selflessly, sedulously. They could be around us helping the marginalized; they could be away from the public gaze tilling soil or tending trees; they could be unidentified pillars of the system; they may be those writing but not being read; they could be waging little battles unrecognized. These are the people who rise above their situations, unmindful of their own struggles. They hear the unspoken and respond before being beseeched. Happiness is not a goal for them; it is their attainment. They have attained a balance between shahi (having the resources to fulfil ones desires) and fakiree (the ability to rise above the trap of such desires).

My father, Bauji, was one such individual. He had a story; it was his life. It is not easy to be critical of your parents while narrating their story, just as they seldom critically evaluate their children. A certain degree of subjectivity is part of that relationship. Otherwise, parents would be like fictional characters whom we analyse and whose characteristics we describe.

Like Bauji, we all have stories; not all of them are told in public. They are preserved in households and narrated in families and mohallas as tales of inspiration. These stories are relevant. Their relevance keeps growing as the stories spread and lead to more conversations between parents and children.

These conversations are important for individual relationships, for families, for societies and for systems. Parents, priests, scientists, academicians, managers, administrators and leaders must engage in such conversation in order to maintain their social contract. A well-meaning conversation can never be a challenge to authority.

This book is an attempt to rekindle that conversation.

T he train was about to leave. He was truly on the horns of a dilemma. The steam engine had sounded the whistle indicating the trains imminent departure. This shrill cry of the engine was enough to raise his anxiety. He was not prepared to leave his son alone in the train. After all, the boy was just nine years and two months old and returning to school for the first time after the short winter break.

It was about ten at night. After a day-long journey in the train from Vadodara (Baroda those days) he and his son had just finished eating the food packed most reluctantly by his wife, who was torn between preparing for her son leaving for school and worrying about a daughter, who lay in her hospital bed fighting a terrible typhoid. The ailment was grave but the doctors prognosis made it graver. The family was not sure whether they would be able to get the girl alive from the hospital.

Sitting in that train with me, my father found it difficult to eat his dinner and the thought that he had left behind his daughter battling a deadly disease, which was known to be severe on children, made his stomach churn. My sister was just about thirteen. As a nine-year-old, I was barely conscious of my fathers troubled mind. In fact, I was nervous about returning to a boarding school where students were subjected to bullying and torment.