Table of Contents

To

Dhapubai

The grand grandmother who made it all possible for us

Contents

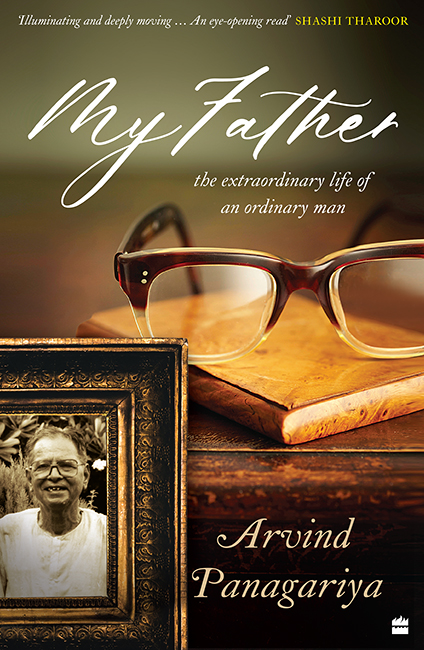

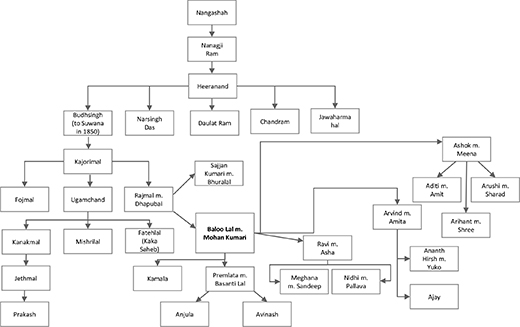

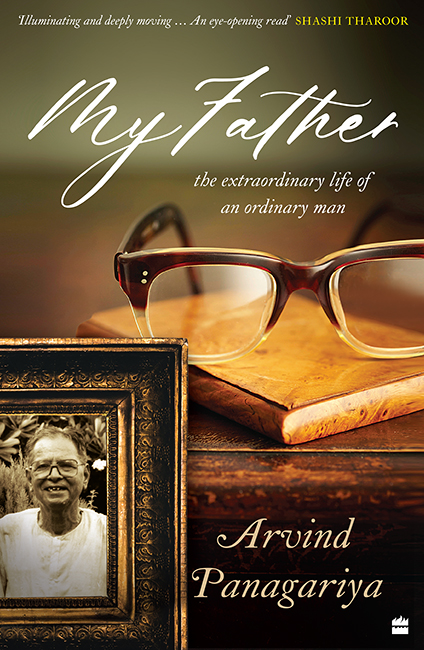

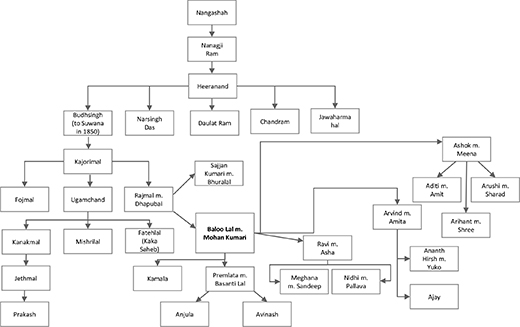

A S THE TITLE OF the book makes amply clear, this is a biography of my father, Baloo Lal Panagariya. The question many readers would ask is why they should be interested in it. I can imagine that at least some readers would have an interest in my autobiography, or a memoir by me covering the period of my close association with Prime Minister Narendra Modi. But what could possibly be the case for a biography of my father, who retired as a deputy secretary in the Government of Rajasthan in 1976 and was barely known outside his own state? I believe I owe the reader an answer to this question at the outset.

First and foremost, the generation born during the 1920s, to which my father belonged, was a special one. It straddled pre- and post-Independence India in a way like no other. It was too young to be at the forefront of the freedom movement, and yet old enough to be inspired by its foremost leader, Mahatma Gandhi, and to join him in his endeavours. Importantly, it was also a generation that came of age just as India was becoming independent and was thus positioned just right to help build the country post Independence. Born in 1921, my father was twenty-six years old at the time of Independence. Therefore, he witnessed Mahatma Gandhi lead India to independence from the British during the formative years of his life and still had many years ahead of him to help build a new nation. Did he rise to the occasion? I will explore this in my book.

India is a vast country; a few well-known national political figures and handful of distinguished members of the civil service in the central government alone could not have built it. Ultimately, the country was the sum of its constituent states, and each state had to be shaped and built. What role did ordinary citizens like my father play in building their states? In many states, the local political leadership was not fully equipped to govern them. At the same time, the number of officers helping run the state governments was small. Those facts empowered even junior officers to exert influence on outcomes. If they were able and motivated to promote the public interest, as my father was, they could influence outcomes in ways that could contribute to the welfare of many generations to come.

The lives of ordinary citizens can also provide a window to the social, cultural and political ethos of their times. What was life like for ordinary citizens in rural India of the 1920s and 1930s? What opportunities existed for them? How did they relate to the national movement, in which Mahatma Gandhi had tried to involve every Indian in one way or the other?

Answers to these questions become particularly interesting when probed through the life of someone who came from a state like Rajasthan, as Rajasthan was formed by merging a large number of independent princely states that local hereditary kings, rather than the British government, ruled. The British government had maintained control over these states through an agent of the governor general, but left their day-to-day administration to the local kings.

The cause of misery of the people in the princely states was often poor governance and exploitation by the local kings. But both Mahatma Gandhi and the Indian National Congress were reluctant to turn the freedom movement into a movement against the local kings. As such, until as late as 1938, they had an explicit policy of limiting the freedom movement to the eleven provinces that the British ruled directly. This fact made it difficult for young men like my father, who grew up in a princely state, to participate actively in the freedom movement. Even in 1938, when the Congress changed its policy, it forbade local movements in the princely states from using its name. Instead, it encouraged each state to form its own Praja Mandal (public association) under whose auspices it could conduct its movement against local misrule.

Apart from these considerations, my fathers life would likely interest and, indeed, inspire many young readers, simply because of its unique trajectory. He was born in a remote village in Rajasthan, in a family so poor that it could not scrape together two square meals a day. The village did not have even a primary school until after he was twenty-one years old. He lost his father at the age of five. At fourteen, he lost his mother. What are the odds that a young man with this history would manage to land up in Jaipur at twenty-five years to serve on the editorial board of Lokvani, the only newspaper in the city, so that he could fulfil his desire to contribute to the freedom movement as it approached its logical conclusion? And who could have predicted that two of his sons would become so successful that the President of India would honour them with Padma awards, one with the Padma Shri and the other with the Padma Bhushan? Yet, that in a nutshell is my fathers story.

I confess that I began this work as my own autobiography. I had known of the extreme hardships my father had faced during his early life from a short autobiography that he had written for circulation among family members. My plan was to include this family background in my autobiography. Therefore, I began with a chapter on my grandmother, whom I had never seen but who had greatly fascinated me from the bit I read about her in Fathers autobiography. After completing the chapter on her, I began the second chapter, which was on my father. I had expected to summarize a few key facts of his life in twenty or twenty-five pages and then turn to my own. But as I progressed, this second chapter kept getting longer and longer, until I realized that the document was turning into my fathers biography. At that point, I also realized that the story of my fathers life was infinitely more interesting than mine. The result of that realization is this volume in the readers hands.

Much of the source material for this biography comes from my fathers unpublished autobiography. Having retired at the relatively young age of fifty-five, he had revived his interest in writing from the time he had helped edit Lokvani in Jaipur. He wrote several books, among which was the definitive work on the freedom movement in Rajasthan titled Rajasthan Main Swatantrata Sangram (The Freedom Movement in Rajasthan). The autobiography was among the last two books that remained unpublished. Instead, Father got his sisters son, who owned a printing press, to print one hundred copies of the autobiography and shared them with the extended family. Therefore, while this biography has my words, the story is as told by my father.

Writing this volume has been a family enterprise. Apart from the members of my immediate family, wife Amita and sons Ananth Hirsh and Ajay, my brothers, Ravi and Ashok, have contributed to it, directly or indirectly. Ravi read the entire manuscript and helped make several factual corrections. My bhabhi, Ashoks wife, Meena, enthusiastically collected many of the photographs. My friend Pravin Krishna, professor of international economics and business at Johns Hopkins University, read the penultimate draft in its entirety and provided some extremely useful suggestions. Given that this is the first time I have undertaken a project of this nature, his encouragement at a critical time proved extremely valuable. Petal Dhillon of the Ministry of Railways in the Government of India and Rajeev Mantri, managing director, Navam Capital also read an earlier version of the manuscript and provided extremely helpful comments. For the final extensive edits to the manuscript, I am deeply indebted to Kripa Raman and Amrita Mukerji, my editors at HarperCollins. However, none of those who have helped in the writing of this book is to be blamed for any indiscretions or errors in it, which remain solely my personal responsibility.