Table of Contents

To my indefatigable mother-in-law

Kamala Somani

who, after getting her first-ever mobile phone at over eighty years of age, today, at the age of eighty-eight, holds the attention of tens of thousands of followers through her poems and social-media posts in four different languages.

CONTENTS

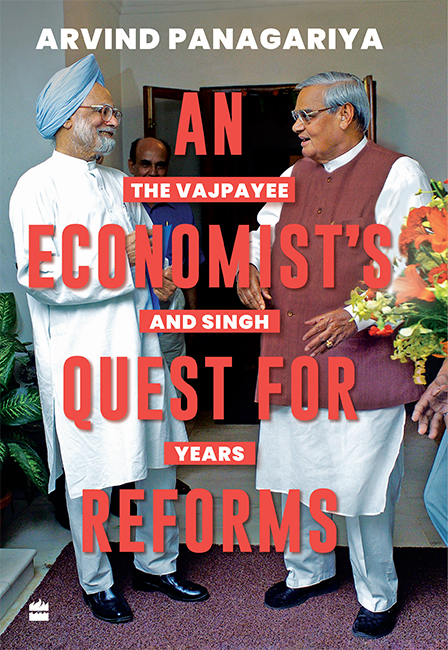

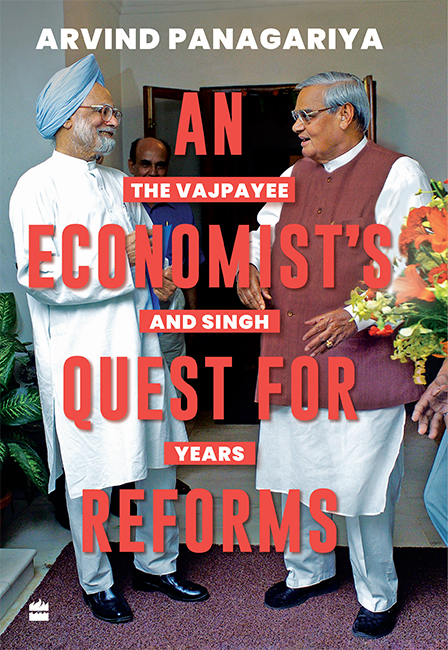

T HIS BOOK BRINGS TOGETHER a selected set of my media articles, written between January 2000 and March 2014, principally for The Economic Times and TheTimes of India. These years approximately coincide with the tenures of Prime Ministers Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh. Although I had made my debut in newspapers in 1989 with an article in TheTimes of India, I only started writing on a regular basis once every month from June 1999.

In the summer of 1999, I happened to meet veteran journalist Swaminathan Aiyar at a conference on India in Washington, D.C. At the end of the conference, Swami asked if I would like to contribute a column to TheEconomic Times once a week. It was an extremely exciting offer at that stage of my life, but I was sceptical about whether I could produce a meaningful column once every week. I asked Swami for some time to think and, having considered the matter for a few days, called him back to ask if I could write once a month instead of every week. He graciously agreed. That got me started, and I have not stopped since, except for a break during 201517 when I served in an official position in the Government of India.

It turned out that sometime in 2012, Swagato Ganguly, the editor of the editorial page of The Times of India, also invited me to write a monthly column for his newspaper. Not willing to let go of such a splendid opportunity, starting in June 2012, I also took on this task for the largest circulating English-language daily in the world. I contributed to it on a continuous basis until just before joining the Government of India as the vice chairman of NITI Aayog in January 2015. After completing my stint at NITI Aayog, I resumed writing the monthly column in December 2017.

In the 1980s, I had been rather pessimistic about whether India would ever achieve the high growth rates necessary to overcome its extreme poverty in my lifetime. The Licence Raj had a tight stranglehold over the economy in those days, and I did not believe that the Indian bureaucracy would ever let go of the privileges this regime conferred upon it. The only time I saw some hope was in 1990, during a speech that then Indian ambassador to the United States, Dr Abid Hussain, delivered at the World Bank. He sounded very upbeat and argued that the growing consumer class would see to it that the command-and-control system of India ends. His words proved prophetic. Even before Dr Hussain had completed his term in Washington, D.C., Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao came to office and, in 1991, dismantled in a single stroke the system that had held India back for four decades.

The monumental steps that Rao took to liberate Indian industry and trade ended my pessimism on India and, soon after in the summer of 1994, I published an article titled India: A New Tiger on the Block? I concluded the article with these words:

Will India accomplish in the next decade what China did in the previous one? Although it is overly optimistic to respond affirmatively, a 6 to 7 per cent annual growth rate in India cannot be ruled out. The world should not be surprised if, in a decades time, it sees another tiger on the block.

It was with this new-found optimism that I launched my column in TheEconomic Times. Even within Indias tough bureaucratic set-up change was possible and more of it was needed. Being both new to the job of policy writing and twenty years younger at the time, I wrote passionately and impatiently, calling for speedy reforms. In real time the change felt slow, even when this was not necessarily the case.

In hindsight, the Vajpayee government was almost relentless in the pursuit of reforms and enacted them in all areas, save a few. I came to appreciate the vastness of the accomplishments of the government only when I sat down to take their full inventory while writing my book, India: The Emerging Giant, from 2005 to 2007. While I did acknowledge many of these reforms in my columns, if I could go back, I would be less critical and more complimentary to the late Prime Minister.

Indeed, I tried to carry out a small correction in my narrative much later in my tribute to Vajpayee on 25 December 2012, his eighty-eighth birth anniversary (see Chapter 6). I began the tribute by noting that along with Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao, he must be credited with laying the foundation of the new India. I went on to recount the numerous reforms he had enacted and suggested that we rename the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana after him as a minimal recognition of his contributions. In concluding the tribute, I noted, Indeed, an even more appropriate recognition of this great son of India will be to honour him with the Bharat Ratna while he still lives. The reader can imagine my delight when the Government of India did indeed bestow this highest honour on him in 2015.

Much to the disappointment of the cheerleaders of reforms, among whom I include myself, Vajpayee lost the parliamentary elections of May 2004. His defeat was wholly unexpected; indeed, so confident was his party of winning the elections that it had chosen to go to polls six months before the end of the governments five-year term. The loss led to the emergence of the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA), which ruled the country for two full five-year terms till May 2014.

Though Dr Manmohan Singh, who had been closely associated with the Rao-era reforms, served as the Prime Minister during both these terms, the real power behind the throne remained Congress President Sonia Gandhi. Mrs Gandhi, it seems, was inspired more by her socialist mother-in-law, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, than her reformist husband, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. As such, under her stewardship, reforms came to a standstill. As I wrote in one of my columns, during this era social spending largely became a substitute for economic reforms.

In fairness, while the UPA didnt advance the cause of reforms, it also stayed away from either disrupting them or introducing policies that could retard growth, at least during its first term. As a result, the reforms already in place could perform their magic. The economy grew at an 8 per cent-plus annual rate, generating revenues for enhanced social spending. Unfortunately, in its second term, the UPA turned outright anti-reform, taking numerous steps that eventually led to a drop in the growth rate to 5.9 per cent during its last two years. Moreover, whereas the UPA had inherited a robust economy growing at 8 per cent from its predecessor, it left a fragile one for its successor.

The narrative in the popular press, even at the beginning of the UPA rule, turned anti-reform. A lot of false claims acquired currency among commentators. Therefore, in addition to offering arguments for why continued reforms were essential and which ones were necessary, I also devoted many columns to exposing the falsehood of many popular ideas. My commentary turned particularly harsh during the last two or three years of the second term of the UPA, when it enacted several Indira Gandhi-style laws that posed an outright threat to future growth.

The Burdens of a Reform Advocate