Sanjaya Baru is director for geo-economics and strategy, International Institute for Strategic Studies, and honorary senior fellow, Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi. He has been chief editor, the Financial Express and Business Standard. His other books include The Strategic Consequences of Indias Economic Performance (2007).

Praise for the Book

Immensely readable and well-writtenIndian Express

Through the retelling of several key episodes, Barus fluent memoir offers insight into the workings of government, the politics of claiming credit, the mechanics of image building, motivations of political figures and their use of the media for personal ends. It is also not short of nuggets for keen Delhi watchersHindustan Times

Sanjaya Baru has done what every American political staffer would do: write an account of his time in office and about the things he or she saw and heard. But he is perhaps the first Indian to do so with certain credibility and panache. [A] spicy insiders viewDNA

Lifts the veil on how the UPA government workedBusiness Standard

Barus book paints an invaluable picture of what went wrong with this decade-long UPA experiment that India has suffered throughMail Today

Explains the nature of corruption in Manmohan Singhs governmentMint

A racy insider account littered with anecdotesTelegraph

Reads like a primer of what not to do in powerIndia Today

Fairly true, though highly subjectiveWeek

An absorbing... narrative of the functioning of a partnership that lasted over a decadeTehelka

A publishing phenomenonBusiness Today

He [Baru] has told the country something it should know, with an account of the years of solitude of a prime minister in his labyrinthDeccan Herald

Essential reading for anyone interested in political historyFinancial Express

What makes Barus book a riveting and important read is that he provides an insiders view, confirms some of what has hitherto only been guessed and gives us valuable, real-time details that are rarely available in a country where recording recent history and memoirs of time spent in public office are not usualAsian Age

It is amusing that the PMO should consider the contents, which only reiterate the widespread belief of Mr Singh having wielded power without authority as fiction and coloured viewPioneer

Of great political importanceNew Indian Express

Baru tells allSunday Standard

Sanjaya Baru

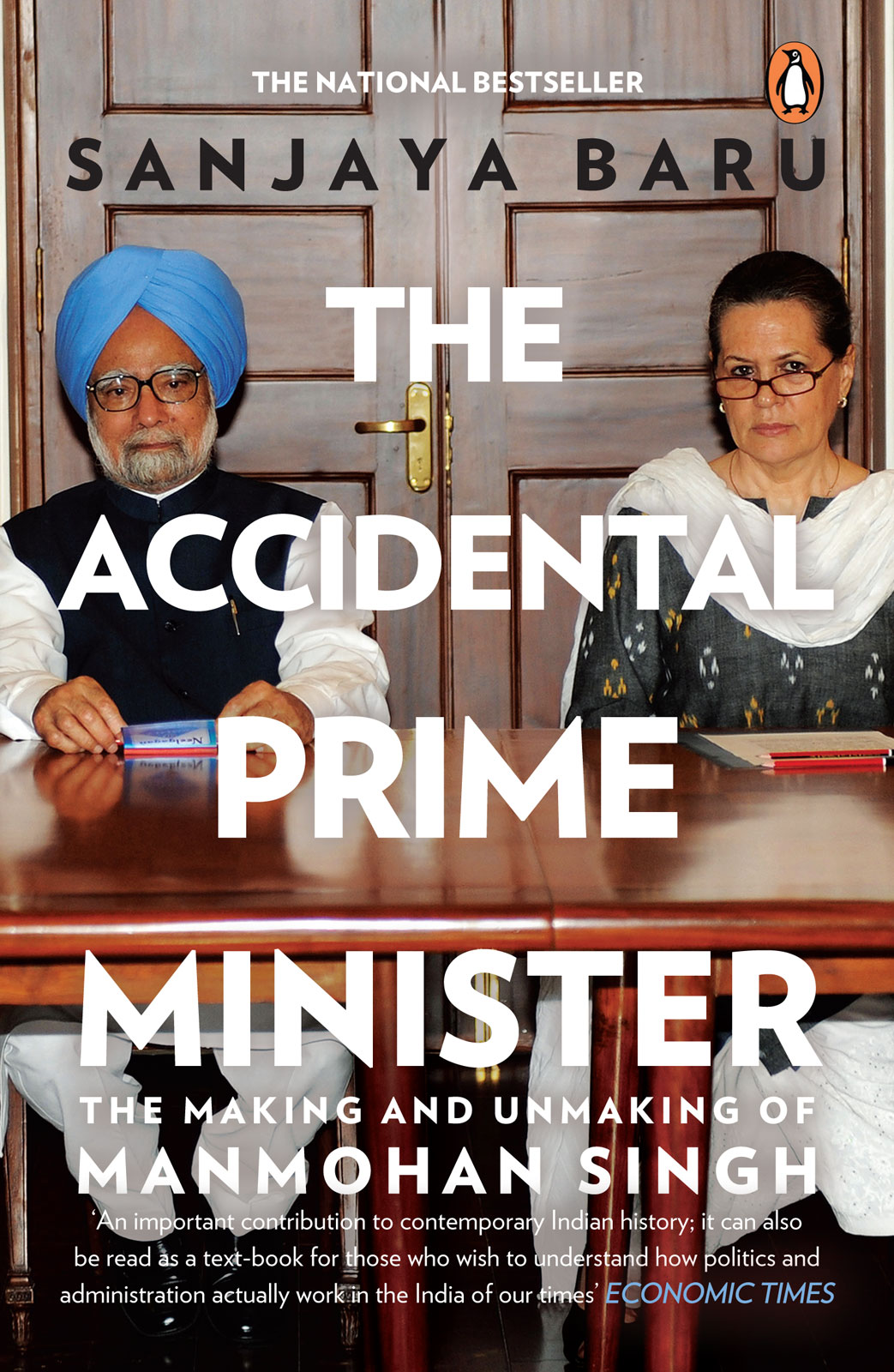

THE ACCIDENTAL PRIME MINISTER

The Making and Unmaking of Manmohan Singh

PENGUIN BOOKS

UK | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

This collection published 2014

Copyright Sanjaya Baru 2014

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Jacket images Chetan Kishore

ISBN: 978-0-143-42406-2

This digital edition published in 2016.

e-ISBN: 978-9-351-18638-0

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

In memory of my mentors

H.Y. Sharada Prasad

and

K. Subrahmanyam

Introduction

The Book I Chose to Write

None of my predecessors in the Prime Ministers Office (PMO) has ever written a full account of his time there. Editors, some far more distinguished than I, who served various prime ministers as media advisers, such as Kuldip Nayar, B.G. Verghese, Prem Shankar Jha and H.K. Dua, did not do so, nor did officials who performed those duties, such as G. Parthasarathy, Ram Mohan Rao and P.V.R.K. Prasad. Parts of Nayars and Vergheses memoirs do, of course, cover that period of their careers, and Prasad has written a series of columns in the Telugu press on his tenure in South Block, but no one has devoted an entire book to his years at the PMO, reflecting on his bosss personality and policies.

This reticence is peculiar to India. In both the United States and Britain, several press secretaries to Presidents and prime ministers respectively, have written freely about their jobs and their bosses. In India, my most distinguished and longest-serving predecessor, H.Y. Sharada Prasad, set a very different tone. An unfailingly discreet and low-profile man, he was Indira Gandhis information adviser, speech-writer and confidant for almost all her sixteen years as prime minister, yet had to be coaxed, over several years, before he agreed to write a few newspaper columns about his time at the PMO.

I first met the legendary Sharada Prasad in 1981 when he was at the height of his career, serving an all-powerful Indira Gandhi who had been re-elected prime minister in 1980 with a landslide vote after being rejected in the General Elections of 1977. I was visiting Delhi a few weeks after my marriage and my wife, Rama, was keen that I should meet family friend Shourie mama, as she had addressed him since her childhood, and his wife, Kamalamma. I met Kamalamma at their home near Delhis verdant Lodi Gardens, but Sharada Prasad himself was hard to meet, simply because he was never home. Finally, we met in his office.

One could then still enter the PMO through its main gate facing Rashtrapati Bhavan and walk up the grand staircase, instead of entering, as visitors now do, by a modest and inelegant side entrance. So I climbed those stairs, and met him in the same room that I would come to occupy more than two decades later. It was four times larger than the editors room in the various newspaper offices in which I had worked, and faced the imposing west wing of North Block, home of the ministry of finance.

I spent a few minutes with Sharada Prasad, noting how humble and low profile a man he appeared in this imperial setting. Since I was, for him, Ramas husband and nothing more, the conversation, naturally, centred around Rama and her parents. I was too overawed by my surroundings to say much. I met him again only after I moved to Delhi to join the EconomicTimes (ET) in 1990, when he came home for our daughters first birthday party. In 1993, after I moved from ET to the TimesofIndia, I invited him to write a column for the paper. He declined, saying he did not feel like commenting on contemporary issues. Undeterred, I asked him, repeatedly, to write about his time in the PMO, but he always had the same cryptic reply: I do not know everything that happened in the PMO. Not only do I not know all sides of the truth, I do not even know how many sides the truth has.