A MERCILESS PLACE

A

MERCILESS

PLACE

The Fate of Britains Convicts after the

American Revolution

EMMA CHRISTOPHER

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further

Oxford Universitys objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright 2010 by Emma Christopher

First published in Australia in 2010 by Allen & Unwin

First published in the United States in 2011 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Christopher, Emma, 1971

A merciless place : the fate of Britains convicts after the

American Revolution / Emma Christopher.

p. cm.

First published in Australia in 2010 by Allen & UnwinT.p. verso.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-19-978255-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Penal transportationGreat BritainHistory18th century.

2. Penal transportationGreat BritainHistory19th century.

3. United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783Influence.

4. PrisonersGreat BritainHistory18th century.

5. PrisonersGreat BritainHistory19th century.

6. Convict shipsGreat BritainHistory18th century.

7. Convict shipsGreat BritainHistory19th century.

8. Penal coloniesHistory18th century.

9. Penal coloniesHistory19th century. I. Title.

HV8949.C47 2011

365.34dc22 2010049032

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

INTRODUCTION

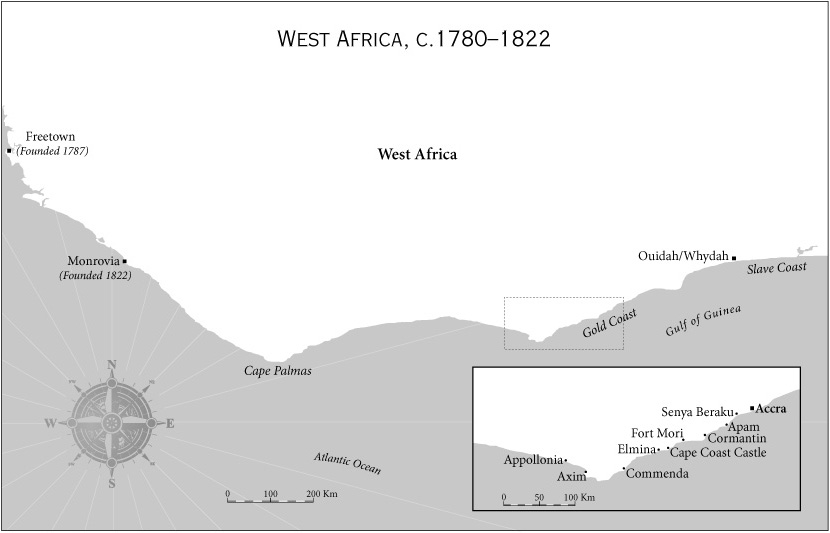

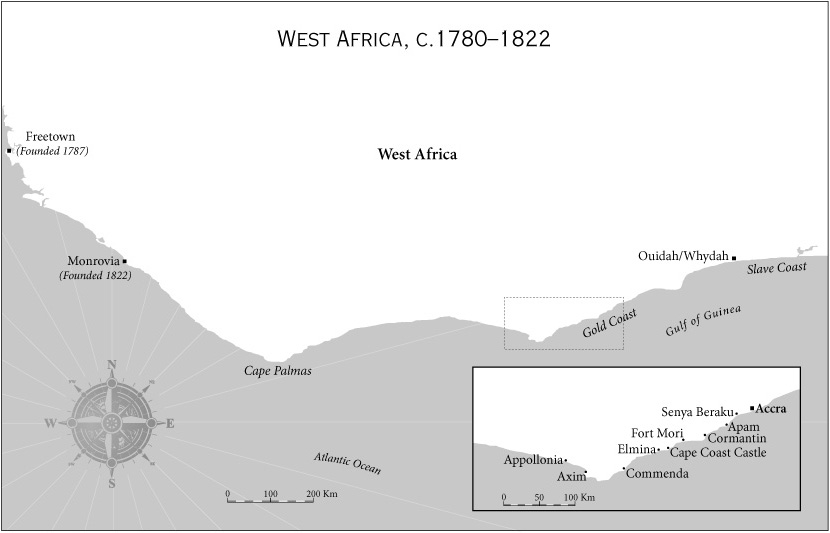

Gore Island, West Africa, November 1781

Trying to regain their land legs, Thomas Maple and his brother Joseph shuffled unsteadily off HMS Mackerel and into the blinding sun. They were a long way from London and the house they had burgled in Swinton Street near Bagnigge Wells, where Nell Gwynne had once entertained King Charles II. Beside them was another convicted housebreaker, Job Massey, a widower who had been unable to explain away some ribbons in his possession. John Plunkett, a sailor who had been caught stealing some gilt-framed mirrors, was less disoriented but awkwardly trying to hide a stigma. Beneath the cuffs of his shabby uniform he curled his fingers over his thumb to hide the fact that he had the letter T for thief branded into the soft flesh of his hand.

Alongside the Maple brothers, Massey and Plunkett were some youths growing up in the criminal system. With the uncertainty of the long-since orphaned, Thomas F ield claimed in court to be about seventeen but his age was noted as sixteen when he boarded the hulks to begin his original sentence of hard labour on the River Thames. A clerk had guessed that John James Smith was only fourteen when he had joined the ship. William Cheatham was said to be a boy when he was convicted of shoplifting at Londons Old Bailey, along with his Fagin-style boss. His criminal overlord, Patrick Madan, had already become known as the famous Madan and should have been standing alongside Cheatham on the parade ground at Gore. The fact that he was not was a saga in itself, another escape which added to Madans legend.

At the head of these criminals, teaching them to drill no less, was William Murray Mackenzie (alias Jefferson, Williamson, Taylor, Ward, Brett and a multitude of other assumed names), a man whose infamy rivalled Madans. His appointment as drill sergeant of these indentured convict soldiers meant that the ranks were a crooks hierarchy with teaspoon thieves, pickpockets and a host of petty chancers guarded by a man whose criminal career had begun with stealing a footmans coat while the servants master was enjoying the services of a brothel, and had progressed to relieving the capitals jewellers of diamonds, emeralds and large sums of money. In fact William Murray Mackenzie had avoided a one-way trip to the gallows, it was whispered, only because he was the black sheep of one of Britains most influential families.

To observers that warm November day, the new arrivals were a very sorry sight. Most were stunted from having grown up malnourished, their faces were pockmarked from disease, and having shared out the uniforms of the few well-dressed men among them, all were poorly clothed. Rather than marching proudly with heads held high, as they had been ordered to do, they stumbled tentatively off the ship. Hidden beneath their trousers, telltale scars revealed why they were so unsteady: the abrasions of iron fetters were still clear around their ankles. For some of them it was the first time in years they had been released from their metal cuffs.

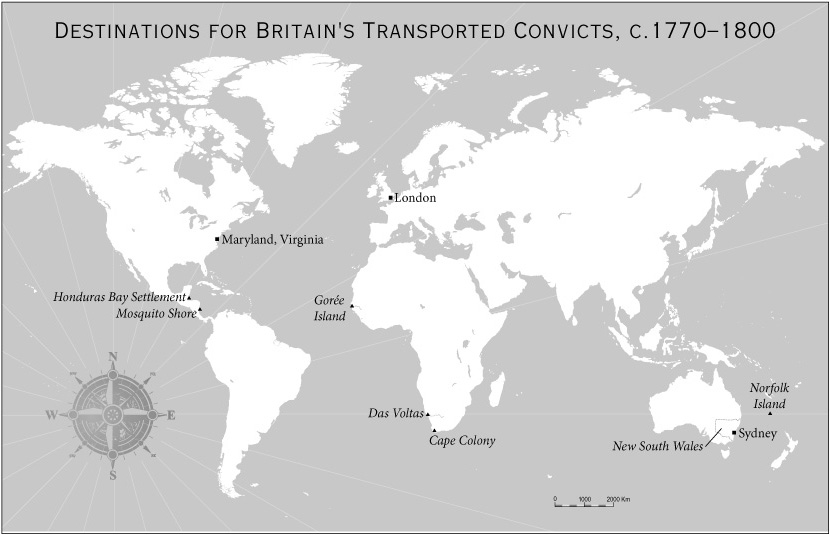

Gore was a short stop on the way to their real destination, the slave-trading forts of the Gold Coast on the southern shores of the bulge of West Africa, where the cold waters of the Atlantic give way to the sultry Gulf of Guinea. Gore was little more than a way station, but as it was the first time they had set foot in Africa and experienced life at a slave-trading post, it seemed to be a window to the future. We can picture them still: frightened boys and men far away from everything they had ever known. Beyond the uniforms worn by the garrison, there must have been little which seemed familiar at Gore.

Most had led parochial lives until this point, their experiences closely circumscribed by poverty. Some had been born in rural squalor and had gone to the city in search of work, but even there they had joined the urban-born in venturing only from dosshouse to pub, chophouse to market. Life rarely encompassed more than rambling the streets in search of employment, warmth and food, and if these failed to materialise then any opportunity to stave off starvation for the time being would do. Being caught shoplifting or hooking a purse from a pocket was not so much a matter of shame as sheer bad luck. Only the rather better-to-do could afford the luxury of seeing morality in the ownership of a handkerchief or teaspoon.

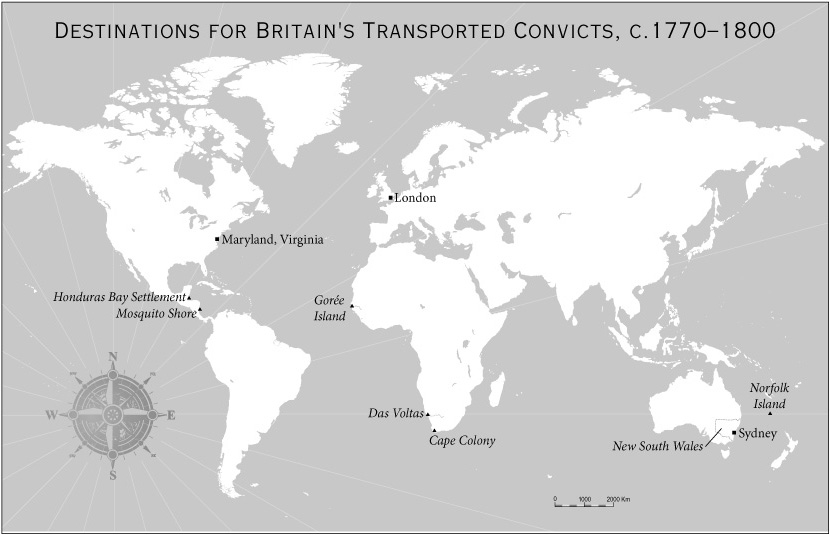

As bad luck went, though, this was well beyond the usual run of things. Bad luck was being tied to the pillory while others threw mouldy fruit or eggs. Bad luck was the painful laceration of flesh as the rhythmic beating and retreating of a whip marked out the required atonement for the committed crime. Rotten luck had previously involved seven or fourteen years, or even a life sentence, banished to the American colonies, a punishment recently replaced by hard labour on the River Thames. The worst luck involved standing in front of a braying crowd with eyes covered, waiting to feel the hempen halter tighten as the world dropped away. But even the most terrible luck of all had never before led to Africa.

Next page