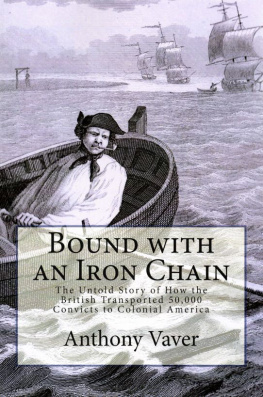

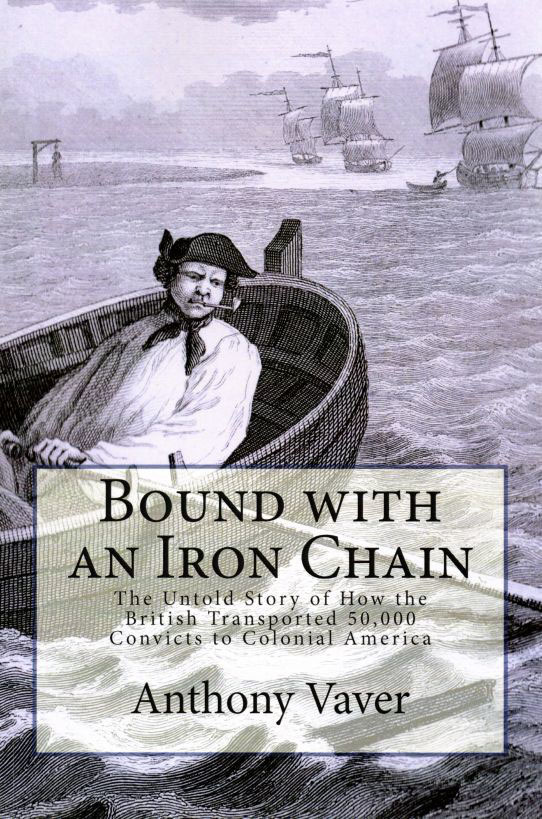

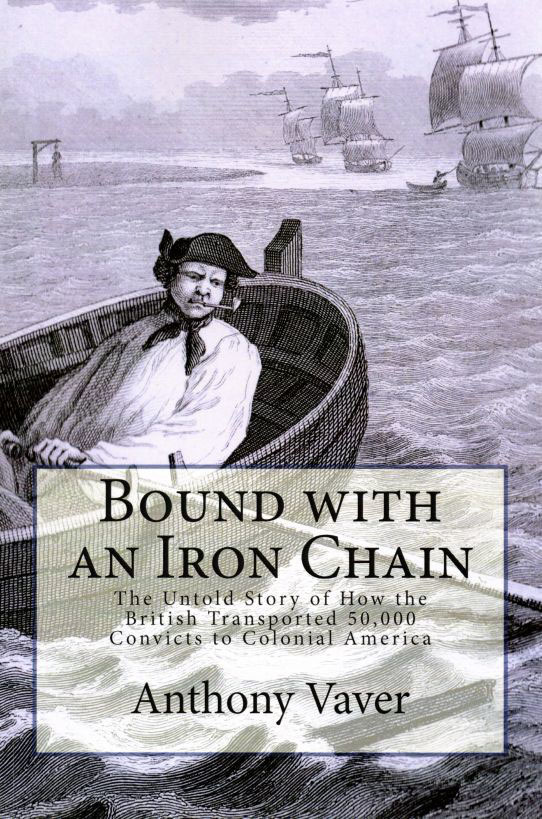

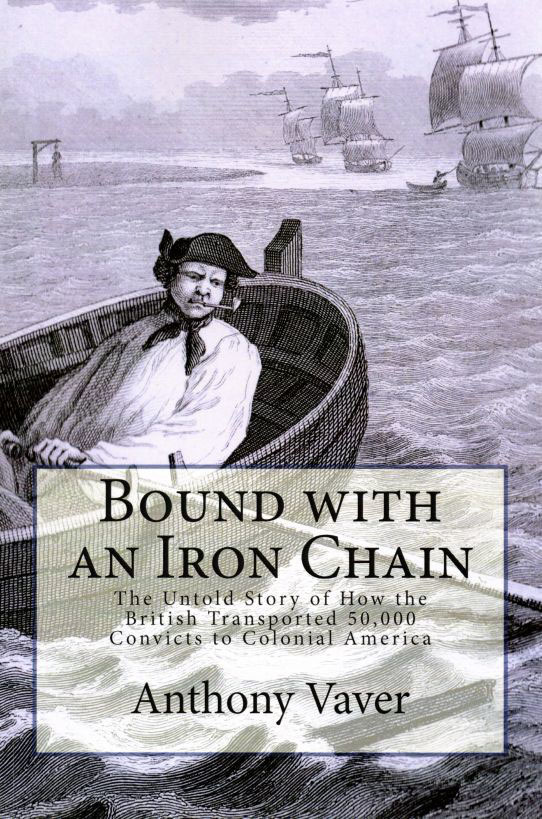

Bound with an Iron Chain:

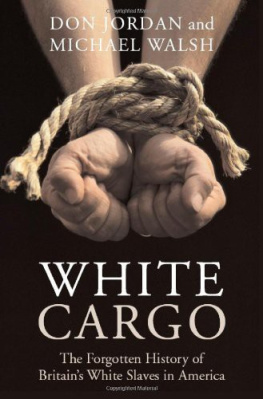

The Untold Story of How the British Transported 50,000 Convicts to Colonial America

By Anthony Vaver

Westborough, MA

www.PickpocketPublishing.com

Copyright by Pickpocket Publishing

All rights reserved

Smashwords edition, 2011

This book is also available in print. Visit http://www.PickpocketPublishing.com for details.

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you are reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Pickpocket Publishing

41 Piccadilly Way, Suite 202

Westborough, MA 01581

http://www.PickpocketPublishing.com

Although the author and publisher have made every effort to ensure the accuracy and completeness of information contained in this book, we assume no responsibility for errors, inaccuracies, omissions, or any inconsistency herein. Any slights of people, places, or organizations are unintentional.

* * * * *

For

Martha, Madeleine, and Audrey,

who are everything to me

* * * * *

Down to the harbour I was took again,

On board of ship bound with an iron chain,

Which I was forc'd to wear both night and day,

For fear I from the sloop should run away.

James Revel, The Poor Unhappy Transported Felon's Sorrowful Account of His Fourteen Years Transportation, at Virginia, in America.

* * * * *

Table of Contents

The seed for my interest in convict transportation to colonial America was planted in 1996 while writing my doctoral dissertation on 18th-century British crime literature. As I was researching the history of crime for this project I came across references to convict transportation to America and thought that this peculiar form of punishment deserved more exploration. I did not follow through on this thought, because such an investigation would have pulled me away from my task at hand, so I tucked the topic away as something to pursue at a later time and place.

Ten years later, I began investigating crime in early America, and convict transportation popped into my head as a subject that could form a perfect bridge between my old knowledge of 18th-century British crime and my new research interest. But when I discovered that more than 50,000 convicted felons were forcibly shipped across the ocean and that they played a significant role in performing needed work in colonial America, I was shocked. How could I not have known more about this form of punishment and the people who were subjected to it? Apparently, I was not the only one who had such a gap in my knowledge of American history. When I mentioned my budding interest in convict transportation to family and friends, their immediate response was almost always, Right, Australia, not realizing that our own American shores had served as the first major destination for British convicts.

I decided that I needed to learn more. As I set out to research convict transportation to America in earnest, I fully expected that Georgia would be the main focus of my investigation. I had a distinct memory from grade school of a map of colonial America with the words penal colony in parentheses under the label for Georgia. Other people I talked with seemed to have a similar memory, because whenever I pointed out that convict transportation started in America and not in Australia, they would then say, Oh, thats right, Georgia. Werent the convicts all sent to Georgia? I soon learned that we were all mistaken. Georgia never served as a penal colonyin fact, none of the American colonies ever didand the only group of transported criminals ever to land in Georgia was a shipment of 40 Irish convicts in the mid-1730s after they were refused entry to Jamaica.

How is it that 50,000 convicts were sent to the American colonies by the British, yet we as Americans remain so misinformed about the history of this massive migration? Clearly, I thought to myself, this story needed to be told.

What is the real story behind the transportation of 50,000 British criminals to the American colonies? Why would someone in England risk committing a crime knowing that he or she could be forcibly transplanted to a foreign land if caught? And what happened to these convicts once they arrived in America? Did they prosper under conditions of unlimited opportunity, as Daniel Defoe claimed in Moll Flanders, or were they ostracized by American colonists and doomed to personal failure? And why did Britain stop sending their convicts across the Atlantic and start shipping them east to Australia?

Bound with an Iron Chain tells the story of British convict transportation to America by focusing on the personalities and experiences of the various people who were involved in it at every level: the government officials who invented this new form of institutionalized punishment; the merchants who amassed fortunes transporting criminals across the Atlantic; the plantation owners in America who put the convicts to work after they arrived; and, of course, the convicts who found themselves bound together with iron chains on a ship heading towards a new land and a new way of life. Convict transportation forces America to re-examine its roots and recognize the significant role that convicts played in establishing and populating colonial America, and Bound with an Iron Chain is my attempt to bring this fascinating and important chapter of American and British history to light.

When quoting from primary sources, I have kept the original spelling and grammar to retain the true character of the passages. The exception is the appearance of the long-s, which looks more like an f and has no modern typographical equivalent. In these cases, I have resorted to using our common s.

Up until 1752, Britain, with the exception of Scotland, used March 25 as the legal start of the New Year, which means dates that fell between January 1 and March 24 before this time were recorded as one year behind current calendar conventions. When citing dates that fell within this period, I have followed the common convention used by historians of adjusting the year up in order to conform to the current practice of counting January 1 as the start of the year.

Under English coinage values in the eighteenth century, 12 pence (abbreviated d.) equals one shilling (abbreviated s.); 5 shillings equals a crown; 20 shillings equals one pound (); and 21 shillings equals one guinea. Currency issued by individual colonies in America generally followed the same conventions, but they had less value than their British equivalent and were not equal in value to currency issued by other colonies. The designation sterling, which specifically refers to British currency, indicates a value higher than money issued by the colonies. To confuse matters even more, currencies from other countries, like Spain, also circulated in the American colonies.