Contents

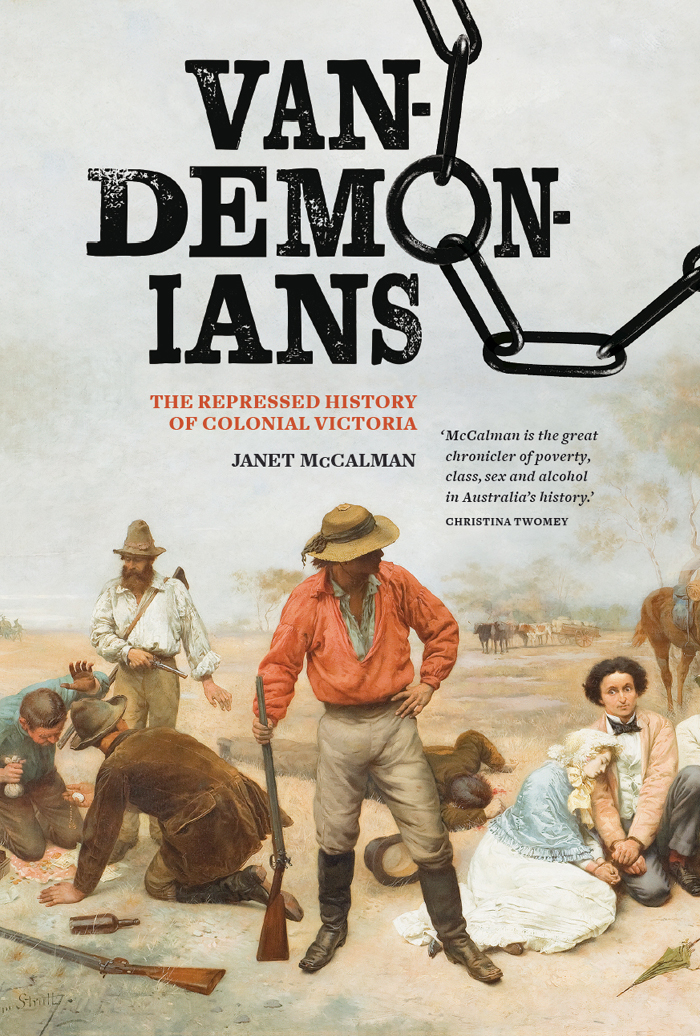

I am of Vandemonian descent. Here is a book, clearly and lucidly written, which enhances my understanding of aspects of my family history while also adding another layer to my consciousness of Australian history.

MARTIN FLANAGAN

One of Australias finest historians, this is McCalman at her very best. In Vandemonians she gives voice to the everyday convict throng, tracing the larger forces that shaped their personal lives and impacted their legacies. Through a meticulous analysis of cradle-to-grave data, this book illuminates the contradictions that shadow colonial history. It also provides salutary historical lessons for the ways in which contemporary carceral practice deals with the fractured lives of the vulnerable and the traumatised.

PROFESSOR ANDREW J MAY

This is number two hundred and one in

the second numbered series of the

Miegunyah Volumes

made possible by the

Miegunyah Fund

established by bequests

under the wills of

Sir Russell and Lady Grimwade.

Miegunyah was Russell Grimwades home

from 1911 to 1955

and Mab Grimwades home

from 1911 to 1973.

THE MIEGUNYAH PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

www.mup.com.au

First published 2021

Text Janet McCalman, 2021

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2021

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Cover and text design by Pfisterer + Freeman

Typeset in Freight Text 11.5/16pt by Cannon Typesetting

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

9780522877533 (paperback)

9780522877540 (ebook)

Contents

In memory of Cecile Trioli and Jenny Wells.

INTRODUCTION

Buzzwinker

Me names Miles; Ellen Miles, remarked an old woman at the City Court yesterday.

And you are charged with vagrancy, stated Sergeant Eason. Can you show the Bench that you have means of support?

How can I support myself when Im continually in gaol and not a shilling coming into the house? What is it at all? What are us old people to do? There is no institution in the country, replied Mrs Miles.

Sergeant Eason: But the country has been keeping you for years.

Mrs Miles: What! The country supporting me. Why, Im supporting the country. Ive scattered my money over the colony for the last fifty years. To tell the truth, Ive spent thousands and thousands of pounds.

Accused, who was found sitting on the hospital steps in Little Lonsdale street, late at night, with a bandage over her eye nearly as large as a pillow, was sentenced to three months, as was also a companion named Bridget Jones.

It was October 1896. Ellen Miles, which was her birth name, was almost seventy years old and she had indeed been scattering her money across the Colony of Victoria for fifty years. She would live for another twenty, still in and out of gaol and benevolent asylums, until she was too frail to escape the Ballarat institution where she would die. It was fitting, as it had been the Ballarat diggers who years before had dubbed her the Buzzwinker, an elaboration of the cant for pickpocket. Later, a locomotive from the Phoenix Foundry that moved with a pronounced waddle was named after her. She was a child of the 1830s and lived until World War I. How aware she ever was of the Great World outside her tiny one of back lanes, brothels and bars, we have no idea, but she was one of those who spanned the history of Victoria from the discovery of gold to Gallipoli. Her underlife threaded through all the turning points; she waddled around the tent settlement of Canvas Town, Melbournes city and suburbs, country towns, and for one mad adventure even Adelaide, her copious skirts concealing her latest stolen goods. Wherever there was a lurk to exploit and a lark to celebrate, Ellen was there.

Her first appearance in the press had been in September 1839: Ellen Miles, aged eleven, charged at the Guildhall with passing a counterfeit half-crown to a shopkeeper in Russell Street, Bloomsbury, London. Mr Field, an inspector at the Mint, said that this child was one of three sisters, all notorious utterers. Ellen had already been in custody thirty times and sported three aliases. Her mother was dead. Her father claimed he could not control her and that it might be an act of mercy to transport her. They had been in and out of St Pancras Workhouse since 1833, and Ellen had graduated at the age of ten after fourteen months in the Childrens Ward on her own. It was there that she may have learned to read and write, and it was there, among the toughest, roughest females in London, that she learned to survive. Both sisters were fierce, voluble and violent, and they followed each other to Van Diemens Land: Ellen transported for seven years in the Gilbert Henderson in 1839, Ruth five months later aboard the Navarino, with a sentence of fifteen.

The Miles sisters were actors in a great historical drama: the transportation across the seas to punishment by exile of around 73 000 men, women and children to Van Diemens Land between 1803 and 1853. They were expected to provide labour for the new colony, to improve themselves through industry, obedience and training, and to contribute to building a productive British society in the Antipodes. If they could control their tongues, suppress their rage and hurt, and do their work, they could survive and, one day, have freedom. A few could return home; others could achieve a stake in the country and establish a colonial lineage. The majority would do neither.

European Australia had a wretched beginning: a society where convicts provided the forced labour for affluent colonists to grab the land from its Indigenous owners and supplant both human beings and their 60 000-year-old culture with new animals, plants, technologies, diseases and, of course, humans. The convicts, however, were not intended to be slaves. As British subjects, they had rights even under sentence: to earn money and save it; to the presumption of innocence and a trial before a magistrate or a jury for colonial offences; and, above all, to the chance of redemption. On freedom from servitude they could become subjects in their own country with all the same rights and privileges according to their social rank. Some men would vote for the first time in Victoria in 1857, and women from 1902Ellen Miles, as Ellen Watkins, was enrolled at the Salvation Army Womens Shelter, 273 Exhibition Street, Melbourne, in 1903. A few secured an old age pension when they lived beyond 1902 in Victoria; they could own property, start businesses and stand for public office. Those who came earliest to New South Wales and Van Diemens Land were the most fortunate in the land grab, and the successful farmers established vast lineages that now include past prime ministers and many other distinguished Australians. But their numbers were small compared with the convicts who came later and entered a more competitive economy where the best land was long gone.