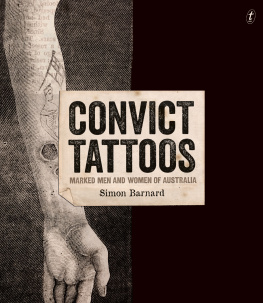

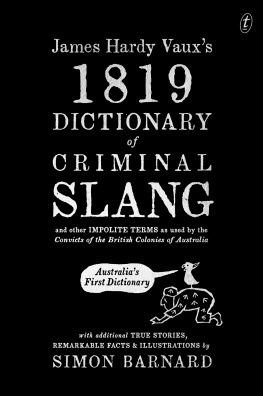

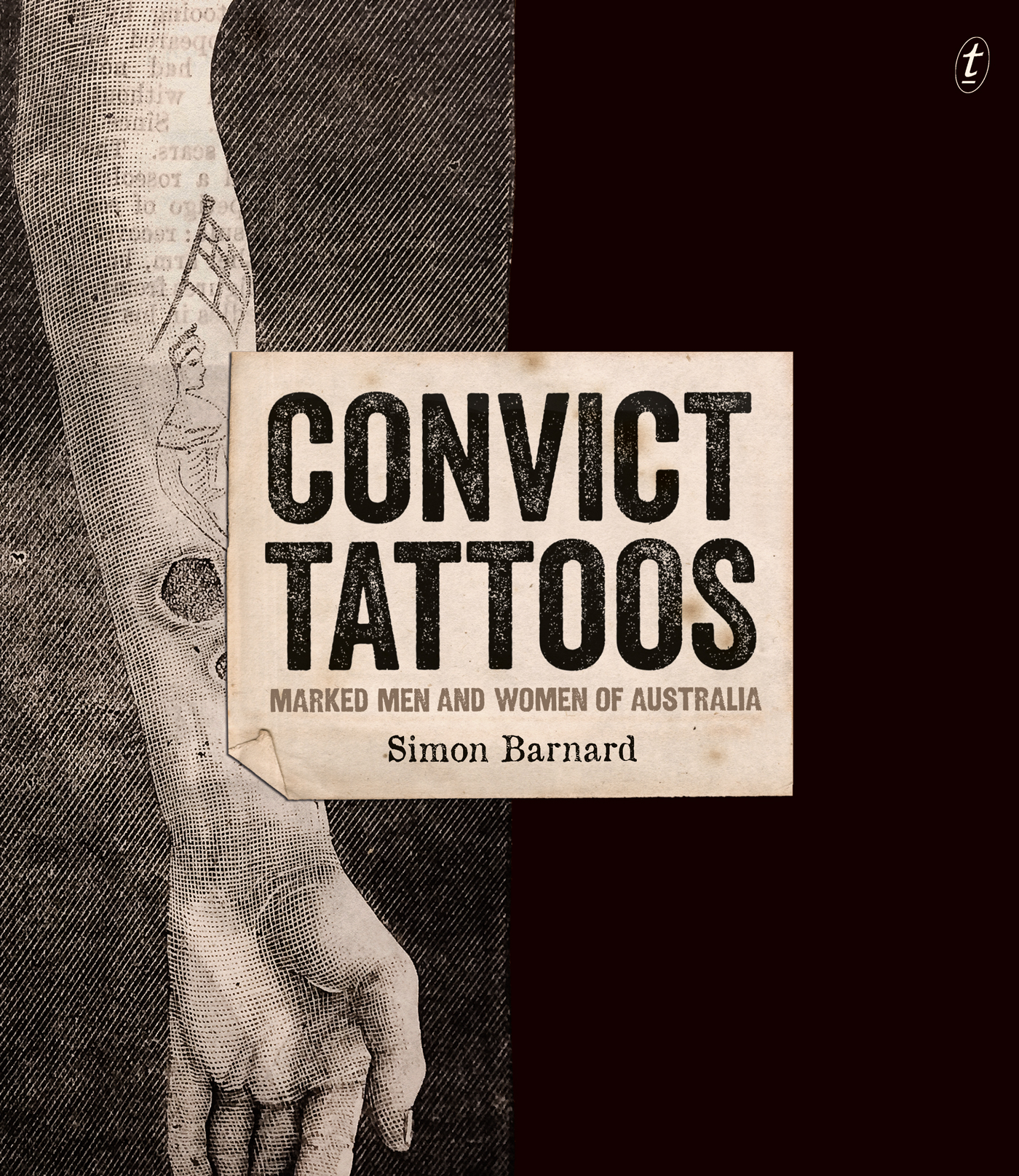

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

textpublishing.com.au

simonbarnard.com.au

Text copyright Simon Barnard 2016

Illustrations copyright Simon Barnard 2016

The moral right of Simon Barnard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

Jacket and text design by Simon Barnard

Index by George Thomas

Printed and bound in China by Everbest

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Creator: Barnard, Simon, author, illustrator.

Title: Convict tattoos : marked men and women of Australia / by Simon Barnard ;

illustrated by Simon Barnard.

ISBN: 9781925240399 (hardback)

ISBN: 9781925410235 (ebook)

Subjects: TattooingAustraliaHistory.

TattooingAustraliaPictorial works.

Tattooed peopleAustraliaHistory.

ConvictsAustralia.

Dewey Number: 391.650994

Simon Barnard was born and grew up in Launceston, Tasmania. He is a writer, illustrator and collector of colonial artifacts. His first book, AZ of Convicts in Van Diemens Land, won the CBCA Book of the Year Eve Pownall Award in 2015. He lives in Melbourne.

simonbarnard.com.au

For Amlie

CONTENTS

Between 1788 and 1868, approximately 166,000 convicts were transported to Australia. The majority were men from the working classes of England, Scotland and Ireland. Typically charged with theft and sentenced to seven or fourteen year terms, they brought with them their own cultural practices, including singing and dancing, and tattooing.

Convicts made up a large proportion of the British community in the early days of colonisationin 1820, convicts constituted ninety per cent of the white population, and by 1840 about fifty per cent. At least thirty-seven per cent of male convicts and fifteen per cent of female convicts were tattooed by the time they arrived in the penal colonies; it is most likely that Australia had the worlds most heavily tattooed English-speaking population in the nineteenth century.

And because the convicts arrived already bearing tattoos, tattooing could be considered the first non-Aboriginal artform to be introduced to Australia.

Names and initials were the most popular tattoos, but convicts also bore trial dates, birth dates and other personal information. William Sutton, a tailor, was tattooed with his initials, the year of his conviction and the tools of his profession: Tailors Sleeveboard Goose Scissors & Bodkin. Most tattoos were symbolic, expressing love or hope, religious beliefs or patriotic sentiments. John Turner was tattooed with a heart, an anchor, a crucifix and Britannia. Tattoos also expressed sorrow, humour, regret, defiance and allegiance. Margaret Fulford was tattooed with the propitious words: Love & Liberty. William Gilby bore the more mindful: William Gilby shun bad Company. For many convicts, tattoos were simply decoration.

The colonial authorities recorded the convicts physical features and personal information when they arrived in the colony, primarily as a means of identification and as a record of their trades and skills. But the process was imperfect. John Perryman was tattooed with JB AB HB MB, which suggests that his last name was Berryman, that his tattoos represented family members, and that his surname was misheard when his details were recorded. Henry Treadwell claimed he was unmarried and without children, but the ring tattooed on his left hand and the woman and girl tattooed on his left arm suggest otherwise.

Tattoos provide a glimpse of the lives of the people behind the historical record, revealing something of their thoughts, feelings and experiencestheir humanity.

The information in this book comes in part from the records of 6806 men transported to Van Diemens Land between 1823 and 1853, and 3374 women transported between 1826 and 1853. One transport ship was chosen for each of these years, and the physical descriptions of all the convicts on board were examined, and their tattoo records collated and analysed. Men were more heavily tattooed than women and with a greater array of imagery. The tattoos of other convicts were also scrutinised, giving an indication of the possible stories behind many of the tattoos, and the relationship between tattoo and bearer. Five hundred women with a history of prostitution were looked at, along with 238 widowed convicts, 155 executed convicts, convicts who had their death sentences commuted, convicts with histories of gang affiliation and convicts who absconded, among others.

Portraits of convicts that appear in this book have been illustrated from their physical descriptions and overlaid on records replicating the originals.

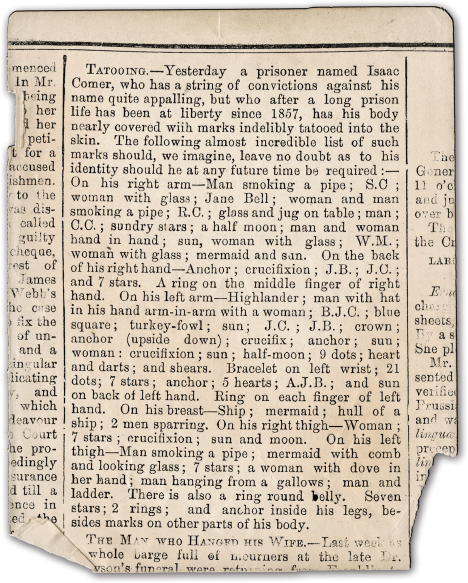

In July 1871, Isaac Comer, aged sixty-one, was marched into the Van Diemens Land Supreme Court to stand trial for stealing gardening tools. Comer was no stranger to the bench. In his hometown of Bath, England, hed served five months for assault and six months for stealing a pig.

Isaac Comer, on trial in Hobart Town.

He was also a disgraced soldier, court-martialled for drunkenness. When, in April 1844, Comer was charged with receiving stolen goods, he was sentenced to fourteen years transportation to Van Diemens Land.

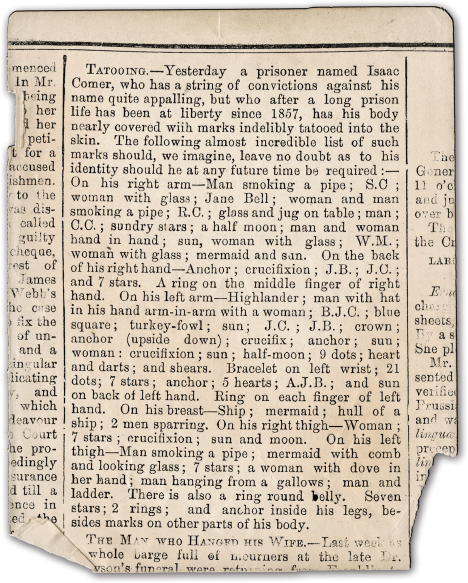

Isaac Comers description in the Mercury, 5 July 1871.

A persons criminal history was integral to the sentencing process. In preparation for Comers 1871 court appearance, a clerk would have leafed through a series of leather-bound ledgers until he found the entries detailing Comer. Though Comer stood quietly in the dock, his record screamed a spectacular secret: beneath his modest attire Comers body was so heavily tattooed he may have been Australias most tattooed man. His gobsmacking collection was such a revelation that the following day a rundown was printed in the local paper.

A cross-check with the records reveals even more. The last line in Comers tattoo description reads seven stars, two rings, and an anchor between legson his yard. The term yard was colonial parlance for penis. Nineteenth-century sensibilities prevented the clerk from writing the anatomical word in official documents and theMercury editor from printing it in the newspaper.

The Black Books were registers of the convict populace. Standard entries listed each convicts name, crime, sentence, trade, literacy, religion, height and age, along with a description of their complexion, head, hair, whiskers, visage, forehead, eyebrows, eyes, nose, mouth, chin and any other noticeable oddities, including tattoos.

Until the introduction of photography in the early 1850s, anthropological classification was primarily limited to description. The result was a stunning collection of intimate detail in the Black Books and an unprecedented amount of paperwork. By the 1830s there was more information detailing Van Diemonian convicts than any other group of people on the planet. Thus we know that Isaac Comer was five foot, eleven and a half inches tall with dark brown eyes, a ruddy complexion and a tattooed yard. His tattoos were so extensive that the clerk resorted to writing them vertically over the preceding entries.