A CARGO of

WOMEN

An absorbing and highly readable account of 100 female prisoners... The result is a full, rounded picture that adds significantly to our understanding of the female convicts, the conditions under which they served their sentences and the lives they subsequently led.

Emeritus Professor Brian Fletcher, University of Sydney

We have plenty of generalisations, but only a few biographical studies of individual cases... one who tries to do more than generalise is Babette Smith. Moving on from a genealogical study of her great-grandmother, she undertook research on the latters fellow-passengers. The result, as Norma Townsend put it in her review, is a painstaking piecing together of the minute detail of lives which would otherwise have been lost in the great sea of humanity.

A.G.L. Shaw, former Professor of History at Monash University

Babette Smiths insightful examination of the women from the Princess Royal concluded that for most of these women Australia was not the fatal shore at all, but a second chance.

Catie Gilchrist, Limits of Repression

... a rich picture of existence and the negotiations that made life what it was in England and the colony.

Deborah Oxley, Convict Maids

The colonial life of Susannah Watson offers an effective rejoinder to The Fatal Shore...

A.T. Yarwood, The Independent

Also by Babette Smith

Mothers and Sons

Coming Up for Air: The History of the

New South Wales Asthma Foundation

A Cargo of Women: The Novel

Australias Birthstain: The Startling Legacy of the Convict Era

BABETTE SMITH

A CARGO of

WOMEN

Susannah Watson and the convicts

of the Princess Royal

SECOND EDITION

This edition published in 2008

First edition published in 1988

Copyright Babette Smith 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Smith, Babette.

A cargo of women : Susannah Watson and the convicts of the

Princess Royal.

Bibliography.

ISBN 978 1 74175 551 0 (pbk.)

Watson, Susannah, 17941877.

Princess Royal (Ship)

Women convictsAustraliaBiography.

994.402082

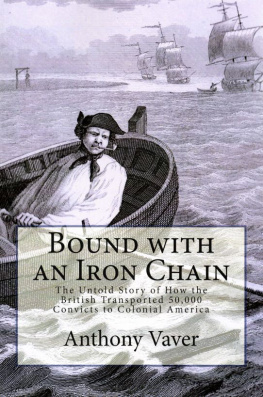

Inside cover: Letter from Susannah Watson

Internal design by Kirby Stalgis

Set in 11/14 pt Adobe Garamond by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my father, Bruce P. Macfarlan, and grandmother,

Amy Macfarlan... with love

contents

Twenty-five years ago, finding a convict ancestor was a real jolt for family historians. Frequently the prisoner, sometimes more than one, had been eradicated so completely that all family knowledge of them had been lost. Before genealogical research uncovered the truth in the late twentieth century many families knew nothing of the first arrival, let alone that he or she came to Australia by transportation.

In many cases the deception was perpetuated by an oral tradition that settlement in Australia began with the convicts child. By the twentieth century, my family had been bamboozled by this means. We knew nothing of the extraordinary life and character of Susannah Watson because we had skipped a generation, erasing Susannah from the collective memory. To the extent the family history was discussed at all, which was not often, in the twentieth century we were told by Susannahs grand-daughter that what we now know to be Susannahs branch of the family began in Australia when Charles Watson (subsequently discovered to be Susannah the convicts bastard son) migrated to Australia, bringing with him a printing press which he used to establish a string of country newspapers.

Susannahs grand-daughter, Amy Watson, had been born only three years before Susannahs death and probably believed this story herself. For adults of that time, however, this version would not wash. Charles was known to be a proud native son. At the time, or shortly after his death, it was said he came from the Hawkesbury area, a place where some of the few free settlers who came to New South Wales during the transportation era established farms. We wasted a lot of time exploring settlement on the Hawkesbury and pondering the nineteenth-century copy of the book The Hawkesbury and RichmondGazette in which Charles appears as a pioneer. The duplicity that led us astray appears on Charles death certificate in 1886, which claimed he was born at the Hawkesbury. His mothers name was only recorded as Susannah, without a surname. There was no entry under father.

It was the Rev. Samuel Marsdens determination to distinguish between married women and concubines, free and bond, that revealed the truth. Convicts child, he recorded bluntly on Charles Watsons birth certificate. So, not a free immigrant after all. In fact, Charles was born in 1830 at the notorious Female Factory in Parramatta at the height of the convict system. The original dissembler was probably Susannahs daughter-in-law, Eliza ne Yeates, who was herself the daughter of John Yeates, a London pickpocket, our second convict ancestor. At the time of Charles death, Eliza would have been the only person in a position to know where the truth needed blurring and what details should only be partially recorded.

There was a limit to how many could deploy the Hawkesbury ruse. In many cases, the convicts themselves either moved awayNew Zealand or Victoria or South Australia were popular destinationsor changed names, which was a useful device to create confusion. The women prisoners are as difficult to track as the men, but at least some of their name changes have more legitimate purposes. Some female convicts were convicted under their maiden name but transported by the married one, often declaring themselves the wife of... [naming the husband] in the hope they would be reunited with their husband in the colony. Women who simply lived with a man, or two or three men consecutively, took his name for the duration of the liaison and registered his children by that name. Arriving as a prisoner in 1829 on the Princess Royal, Susannah Watson was one of these. Transported as (Mrs) Watson, she lived as Clarke for the bulk of her 14-year sentence, for reasons which will be revealed later. Fortunately, like many women prisoners, she took care to record the fathers of her Australian children within their baptismal name. Charles Isaac Moss Watson was the son of Isaac Moss, and John Henry Clarke Watson the son of John Clarke. As her descendants, it was our good fortune that she registered Charles, at least, as Watson, probably because she did not have a continuous relationship with his father. Johns birth was harder to trace because at that time he was listed as Clarke. Once free, Susannah reverted to her legal name, Watson.

Next page