GRAPHIC DESIGN AS

COMMUNICATION

What is the point of graphic design? Is it advertising or is it art? What purpose does it serve in our society and culture? In this companion volume to Fashion as Communication, Malcolm Barnard explores how meaning and identity are at the core of every graphic design project and argues that the role and function of graphic design is, and always has been, communication.

Examining a range of theoretical approaches, including those of Shannon and Weaver, Lasswell, Barthes, Derrida and Foucault, the author argues that graphic design should be approached semiologically and treated as a language rather than a form of art. He analyses how meaning is constructed and communicated, and explains how graphic design relates to this construction and reproduction of meaning.

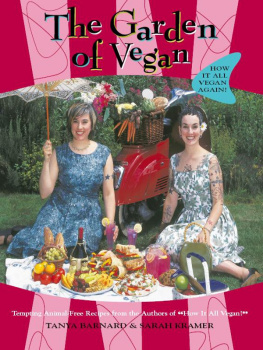

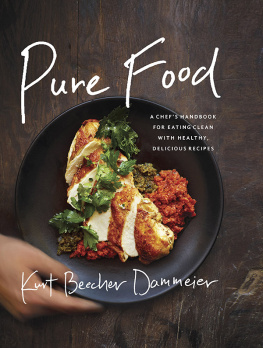

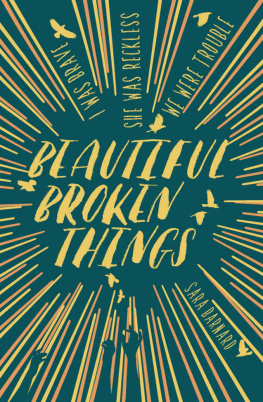

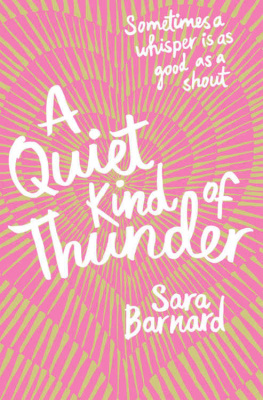

Taking examples from advertising, magazines, illustration, website design, comics, greetings cards and packaging, Graphic Design as Communication looks at the ways in which graphic design contributes to the formation of social and cultural identities, discussing the ways in which racial/ethnic, age and gender groups are represented in graphic design, as well as how images and texts communicate with different cultural groups.

Finally, the author explores how graphic design relates to both European and American modernism, and its relevance to postmodernism and global-isation in the twenty-first century and asks why, when graphic design is so much an integral part of our society and culture, it is not better studied, acknowledged and understood as art is.

Malcolm Barnard is Senior Lecturer in the history and theory of art and design at the University of Derby. His previous publications include Fashion as Communication (second edition, 2002), Art, Design and Visual Culture (1998) and Approaches to Understanding Visual Culture (2001).

GRAPHIC DESIGN AS

COMMUNICATION

Malcolm Barnard

First published 2005

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

2005 Malcolm Barnard

Typeset in Times by Book Now Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Barnard, Malcolm, 1958

Graphic design as communication/Malcolm Barnard.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Graphic arts. 2. Communication in art. 3. Symbolism in art. I. Title.

NC997.B28 2005

741.6dc22 2004014488

ISBN 0415278120 (hbk)

ISBN 0415278139 (pbk)

TO MY STUDENTS

AUT DISCE

AUT DISCEDE

CONTENTS

Conclusion

8 GRAPHIC DESIGN AND ART

ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I'd like to thank Rebecca Barden, Mark Durden, Helen Faulkner, Rob Harland, Gus Hunnybun, Matt Jones, Rob Kettell, Helen Neil, Zora Payne, Richard Tyler, Josie Walter and Julia Welbourne, for variously making/helping me teach this stuff, recommending reading or examples, providing illustrations, rubbishing my arguments and other welcome advice. Heather Watkins and the staff in the Learning Resource Centre at the University of Derby helped with Inter-Library Loans and Inter-Site Favours.

Thanks are due to all of the copyright-holders who granted permission for the illustrations. Thanks to Calum Laird, Parker's Seeds, The Pistachio Information Service and D.C. Thomson for permission to use material from The People's Friend and My Weekly. And to the Research Group in the School of Arts, Design and Technology at the University of Derby for supporting a semester out of teaching. Every effort has been made to trace all the copyright-holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers will be pleased to make the necessary arrangements at the first opportunity.

1

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Most people see more examples of graphic design before they get to work than they see examples of art in a year. Before they are even fully awake, most people will see the numbers and letters on the faces of alarm clocks, the colours, shapes and lettering on tubes of toothpaste, the letters and symbols on taps and showers, the signs for On and Off on the kettle, the packaging of their tea or coffee, the station idents on morning television and the print, photography and layout of the newspaper. This is before they climb into cars (with front and rear badges and logos, and a dashboard full of tiny pictures, symbols and numbers) or onto buses and trains (encrusted with corporate identities, advertising and more badges and corporate logos), and make it along the road (adorned with advertising, bus-stops, shop-fronts and other signs giving warnings, instructions, information and directions), to work (where yet more graphic design informs them of the location of Reception, lavatory, lift and, in some cases, library). Graphic design is everywhere. Yet it is often taken for granted, passing unnoticed and unremarked as it blends in with the visual culture of everyday life.

Graphic design is even unnoticed by those unacknowledged legislators of the lexical world, the compilers of dictionaries. It may come as something of a surprise to learn that graphic design and graphic designer are included in neither Chambers English Dictionary (1988) nor The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1990 imprint). Writing in 1993, Alina Wheeler (1997: 845) noted that no American dictionary included these phrases either. Moreover, assuming that anyone who has got this far already has an inkling of what graphic design is (why pick up the book otherwise?), the fact that entire cultures have a blind spot to something that is so obvious, that literally stares people in the face every time they turn on a tap, glance at a newspaper, open a pack of gum or click on a website, will be as inexplicable as it is surprising. As Wheeler points out, these dictionaries pride themselves on being up to date: they encourage members of the public to inform them of new words and they employ teams of specialist experts who are constantly alert to the spoken and written appearance of novel words. How did they miss graphic design/er? There are even quite respectable universities with departments of graphic design, who churn out thousands of eminently employable graphic designers every year. How is it that the words denoting them and the work they produce are not included in dictionaries?

One explanation may begin with the idea that graphic design passes unnoticed. Newspapers, gum-wrappers and websites are read for their content, not for their layout, choice of typeface or use of colour. Most people don't even know they are reading the letters or words on their bathroom taps; they study the newspaper headline for the politics or the sports results and they pick up the gum with the blue wrapper and white writing. What most people do not do is admire the sans serif in the bathroom, nor do they marvel at the clarity of Helvetica on the page or appreciate the way the nutritional information has been incorporated into the overall design of the wrapper. The graphic work is invisible in that sense and the hitherto insupportable claim of lazy and irresponsible designers everywhere, that they are merely providing a vehicle with which to communicate someone else's message, suddenly finds a prop. If most graphic design passes most people by most of the time, then it is no wonder that the language of most people, as it is reported by dictionaries, does not include the words graphic design.