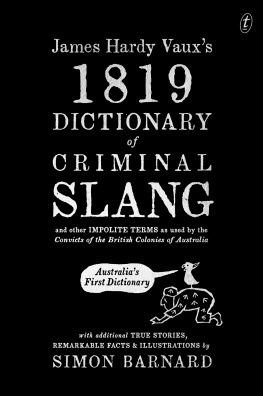

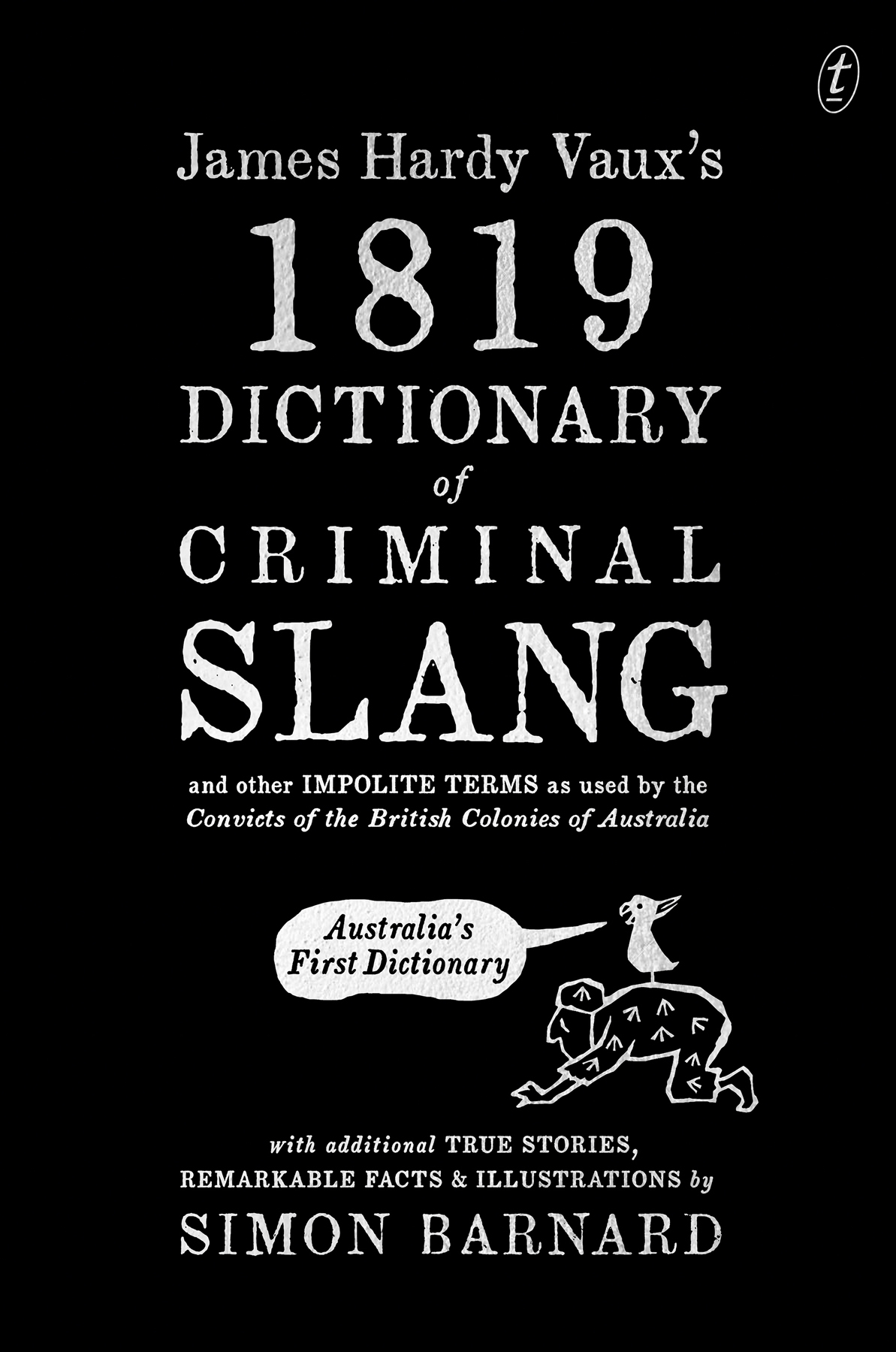

In the early 1800s magistrates in the Australian colonies were often frustrated by the language used by reoffending convicts to disguise their criminal activities and intensions. Convict clerk James Hardy Vaux came up with a useful idea: a dictionary of slang and other terms used by convicts. And so, in 1812, he compiled what was to be Australias first published dictionary.

With words such as fence (a receiver of stolen goods), flesh-bag (a shirt), flip (to shoot); galloot (a soldier), kid (a child thief), knuckle (to pickpocket), ramp (to rob out in the open), ruffles (handcuffs), screw (a skeleton key), serve (to rob), stamps (shoes) and wrinkle (a lie), Vauxs dictionary is a fascinating account of convict language, including the origins and early usage of several words that have evolved to become part of Australian English today. And Simon Barnards illustrations and supporting accounts of individual convicts and their criminal antics complement this lively picture of Australias convict history.

Table of Contents

Australias first dictionary, A New and Comprehensive Vocabulary of the Flash Language by James Hardy Vaux, printed in London in 1819, was a collection of words and terms used by convicts to describe and sometimes disguise their crimes. For the administrators of the convict system it provided a valuable insight into criminal life and the means to understand convicts charged with further offences.

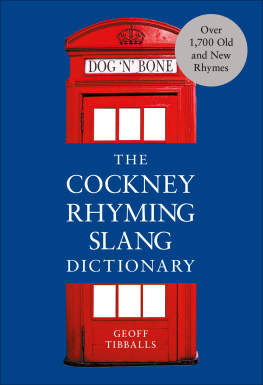

Approximately 164,000 convicts were transported from British and Irish ports to the Australian colonies. Their slang, formally termed cant and informally known as flash, was an ever-evolving language steeped in the cultural melting pot of the British underworld. In the early days of colonisation a court-appointed interpreter was often required to translate the depositions of the witnesses and the accused.

The dictionary proved to be hot property. After it was released in Australia it appears to have sold out. In 1821, a Van Diemonian lawyer misplaced his copy and tendered a reward of five shillingsthe cost of a new copy. Twenty years later the dictionary was in its fourth printing. Another Van Diemonian lawyer was wryly reported to be in dire need of a copy when he struggled to explain the terms on the cross and on the square to a jury.

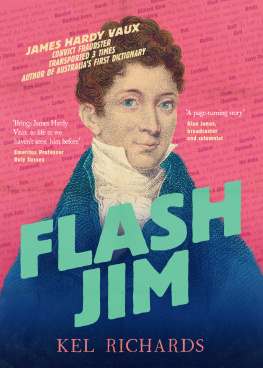

The dictionarys author, James Hardy Vaux, was a convict himself, a habitual offender transported from Britain to New South Wales three timesin 1801, 1810 and 1831. By his own admission he was guilty of buzzing, dragging, sneaking, hoisting, pinching, smashing, jumping, spanking, and starring; together with the kid-rig, the letter-racket, the order-racket, and the snuff-racket.

Vaux was born in Surrey in England in 1782. Well educated and of respectable parentage, he rejected an apprenticeship, gainful employment and naval service for a rakish life of villainy. In 1812, while imprisoned at the Newcastle Penal Station and employed as a clerk, he compiled the dictionary, which he cheekily dedicated to the stations commandant:

I trust the Vocabulary will afford you some amusement from its novelty; and that from the correctness of its definitions, you may occasionally find it useful in your magisterial capacity.

I cannot omit this opportunity of expressing my gratitude for the very humane and equitable treatment I have experienced, in common with every other person in this settlement, under your temperate and judicious government.

Vauxs dictionary was instructive but also entertaining. It was read more widely than just within the court system, and as people became familiar with the terms it described, the usage of those terms increased. The true language of English thieves is becoming the established language of the colony, wrote British colonial administrator Edward Gibbon Wakefield in 1829.

Fearing that slang would normalise and perpetuate criminal behaviour, many authors, journalists, diarists and clerks ignored, omitted or edited it out of their writing. Indecent, profane and abusive language, as specified in the rules and regulations governing the major sites of imprisonment in colonial Australia, was forbidden.

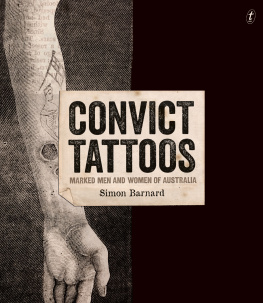

The effect that language had on children was of particular concern. When Vauxs dictionary was first released it was deemed dangerous to the young. After visiting Australia in 1836, Charles Darwin concluded that female convicts taught their masters children the vilest expressions, and it is fortunate if not equally vile ideas. But attempting to silence convicts was futile. Informal language was a vital form of expressionapproximately half of all convicts were illiterate. Sung, shouted, screamed and whispered, slang was also scrawled into bibles, stippled onto coins, scratched into cell walls and pricked into convicts skin.

The language of the convicts endures. Words such as seedy, serve, snitch, snooze, square and stash are now commonplace. Slang contributed to the shaping of an Australian identity: danna, meaning human excrement, gave way to dunny. Togs became swimming costume. Ridgegoldbecame ridg y didgegenuine, good. Larking probably became larrikin. Swag is the origin of swagman. And grog still means grog.

This book contains Vauxs original dictionary, reproduced in its entirety, entry by entry, along with stories of convicts and their crimes, quoting the language used to report them in court documents, newspaper articles, diaries and letters of the time. Some entries also include etymological information, tracing the possible origins of Vauxs terms. Vauxs writing is reprinted verbatim in all entries except E, X and Z, which were omitted by Vaux. Here, they have been collated from contemporaneous sources.

The year of this books publication, 2019, marks the 200th anniversary of Vauxs original work. In 2012, first edition copies of his two-volume set sold for US$13,750. In one volume the original owner noted:

I knew this Gentleman in SydneyHe lives near me & I saw him frequently. But notwithstanding his intentions of reform, he had been recently turned out of the Police Office, where he had an appointment as Clerk. At this period he was gentleman at large. He dresses well, & looked genteellybut nobody knowing how he lived, he was still regarded as a suspicious character.

Vaux, whose name was synonymous with crime, was infamous the world over. Yet he remains an elusive figure. Following his release in 1841, the then fifty-nine-year-old disappeared. But thanks to his handiwork the whids and games of lagd coves, mollishers and kids remains out-and-out flash.

ANDREW MILLERS LUGGER: A kings ship or vessel.

A lugger is a small sailing ship fitted with a four-cornered lugsail, and Andrew Miller was an eighteenth-century naval lieutenant who was jokingly said to have conscripted such a multitude of sailors that he owned the Royal Navy. A total of 825 vessels transported convicts from British and Irish ports to the Australian colonies. The vast majority were not Andrew Millers luggers, but rather privately owned vessels contracted by the British government.

AREA SNEAK, or AREA SLUM: The practice of slipping unperceived down the areas of private houses, and robbing the lower apartments of plate or other articles.