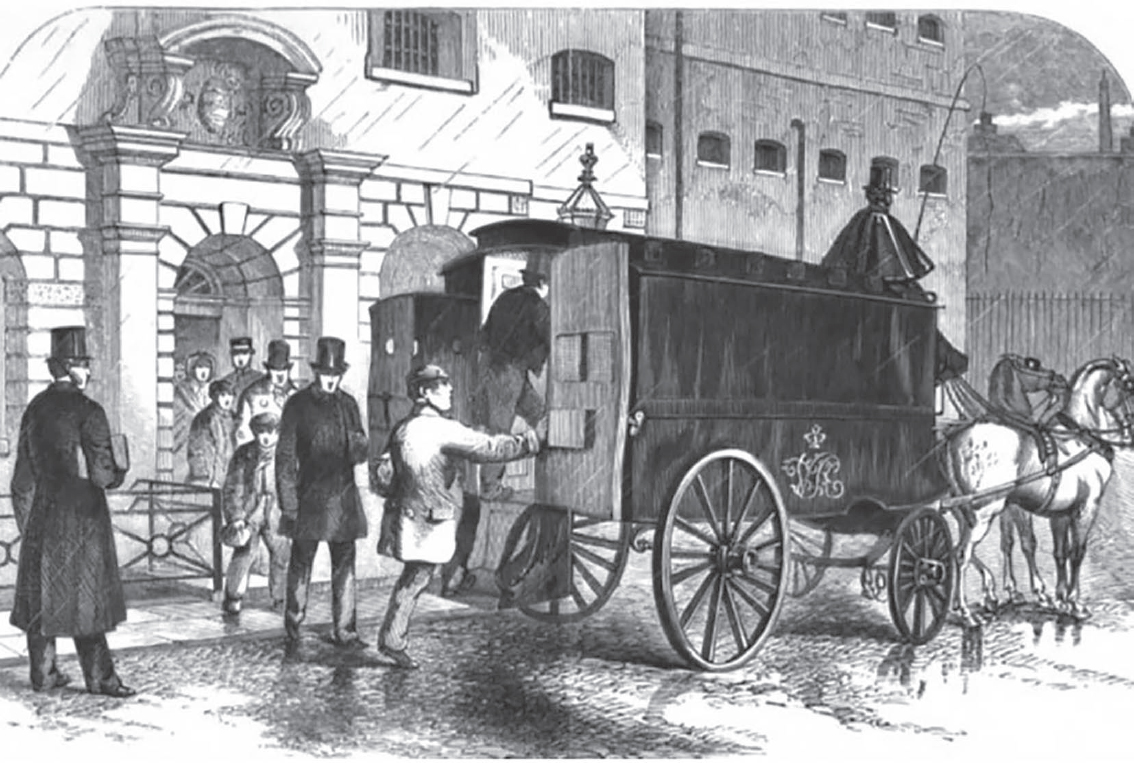

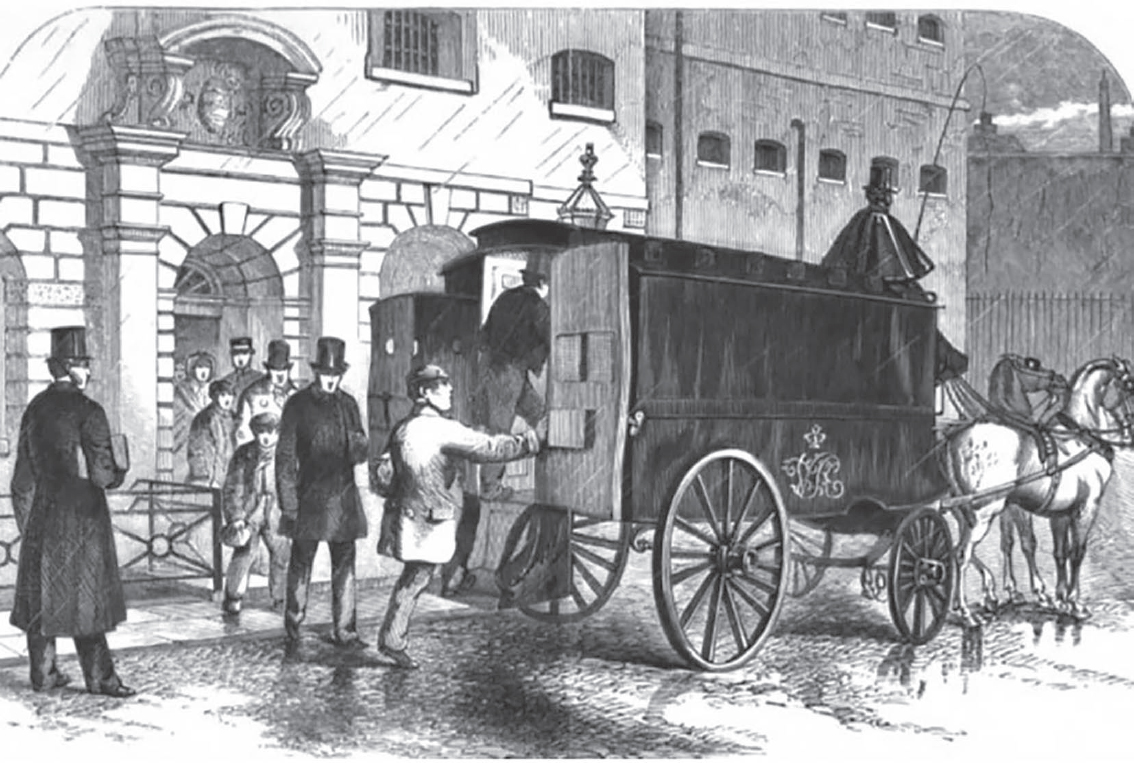

Prisoners being escorted to gaol c.1861. (Authors Collections)

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

Pen & Sword True Crime

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Helen Johnston, Barry Godfrey, and David J. Cox 2016

ISBN: 978 1 47382 373 0

PDF ISBN: 978 1 47388 108 2

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47388 107 5

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47388 106 8

The right of Helen Johnston, Barry Godfrey, and David J. Cox to be identified as the Authors of this Work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd,

Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Introduction to the Convict Prison System

T he convict prison system was established in Britain from the 1850s onwards partially in response to the ending of convict transportation to Australia. During the first half of the nineteenth century discontent with the convict system grew in Australia, and colonies there refused to take anymore convicts sent out from Britain. Eventually the British state conceded that a new system would have to be developed and that people sentenced in Britain would be securely held at home until they were released. In all, ninety prisons (for both serious and minor offenders) were built or added to between 1842 and 1877. Joshua Jebb, then Surveyor-General and later Director of Convict Prisons, designed a system of penitentiaries that were administered and managed by the government and which would hold all offenders sentenced to long custodial terms. When transportation was removed as a sentencing option for the courts, it was replaced by penal servitude (Penal Servitude Act 1853). Instead of a set number of years banished to countries overseas, inmates would serve a shorter period of penal servitude inside a convict prison on the British Isles. For example, seven years transportation was replaced with four to six years penal servitude. During the early years of the convict prison system approximately 10,000 offenders were sent out to Western Australia at the request of colonists there, but this ended in 1868. From that time on all serious offenders, with the exception of those sentenced to death, served periods of long-term imprisonment in the UK. The sentence of penal servitude lasted for nearly 100 years as part of the criminal justice system and left an enduring image of British imprisonment on the popular consciousness. The convict shackled and at work on the moors, or clothed in the uniform with broad arrows or crows feet identifying them as government property and impeding their escape, is often the way in which popular culture remembers Victorian imprisonment.

The sentence of penal servitude was made up of three sections: the first was a period of separate confinement, then a period on the Public Works and then, subject to conditions, release on licence. Initially, the minimum sentence of penal servitude was four years: one year in separate confinement and three years on the Public Works. Separate confinement was a regime of isolation during which prisoners were prevented from having contact and communication with other inmates; they were held alone at all times, labouring, sleeping, and eating in their cells. Male prisoners worked at tailoring, weaving, shoe, bag or mat-making, picking oakum (tarred rope used for caulking ships) and female convicts undertook needlework and knitting. Convicts came out of their cells to attend chapel and to go to daily exercise; during such time they would have had silent association with the other prisoners. Millbank and Pentonville prisons in London were both used for the separate confinement of male and female prisoners and after Millbank closed in 1890, Wormwood Scrubs was used instead. The government also rented cells from local prisons, for example, at Wakefield in England and Perth in Scotland, where convicts underwent a period of separate confinement. After completing separate confinement, prisoners moved to the Public Works or convict prisons.

The longest period of the penal servitude sentence was spent on Public Works, and, as the name suggests, prisoners were put to labour here for the benefit of the public. All of the convict prisons were in London and the south of England. Male prisoners on Public Works were held in Brixton, Chatham, Chattenden, Dartmoor, Dover, Lewes, Maidstone, Parkhurst, Portland, and Portsmouth. Female prisoners underwent Public Works at Fulham Refuge and at Woking Prison for most of the nineteenth century; both Parkhurst and Brixton had housed women in the early years of the convict system but both were used only for short periods of time. In the 1890s, Aylesbury Prison started to take female prisoners and during the 1920s and 1930s, female convicts were also sent to Liverpool and young women to borstal training at Aylesbury. Convicts worked at building docks and sea defences, on excavations, in quarries, or they made bricks and cleared moorland. There were other superior jobs such as blacksmith, carpenter or work in the bakery. Those who were unable to undertake such heavy work were put to labour on farms and women were employed in the laundry (most of which was for the whole convict system) as well as in knitting and needlework.

Convicts worked in association i.e. alongside each other at labour, though communication was strictly regulated to what was necessary for work. At night convicts would sleep and eat in separate cells. The internal regime also encompassed what was called the progressive stage and marks system; as the name suggests convicts progressed through stages based on time periods and they earned marks. They were required to meet a certain number of marks each day in order to progress to the next stage. Prisoners worked through stages from probation to third, second, first and then to special stage; promotion was based on their good conduct and industry and in the first stages on time served. Convicts earned between six and eight marks per day based on the degree of effort and at each stage would receive small benefits to alleviate their confinement and this might include being able to write or receive a letter, being permitted a visit from a relative, or an extra period of exercise during the week.

The progressive stage system was a carrot and stick approach; marks were earned in exchange for gained better conditions but it was also underpinned by an extensive system of punishments. Stage marks and remission marks could be lost for breaches of the prison rules and regulations and prisoners could be moved back a stage or two. They might be required to earn more stage marks before progressing or they might lose remission marks which would reduce the number of days early they might be released on licence from their sentence. Prisoners were also punished through dietary punishment such as bread and water for three days, or they might be sent to close confinement (basically solitary confinement) or a refractory cell (punishment cell). Women could also be placed in a very stiff and uncomfortable canvas dress, whilst men could be made to wear what was known as a parte-coloured jacket (basically a multi-coloured garment that immediately marked them out as wrongdoers within the prison). Both men and women could also be placed in handcuffs, or in more severe cases, in a straitjacket. For the most serious offences against prison officers, male offenders could be flogged.

Next page