The gatehouse of HM Prison Wormwood Scrubs, c . 1900.

It has been my pleasure to encounter some most helpful curators and historians in the research and compilation of this book. I would like to mention the following in particular: Stewart P. Evans; Dr Vic Morgan; Dr Stephen Cherry; Robert Bell, assistant curator of the Wisbech and Fenland Museum; Stewart McLaughlin, serving prison officer and curator of the Wandsworth Prison Museum; Christine and David Parmenter; Jenny Phillips; Theo Fanthorpe; Ian Pycroft; Elaine Abel; Robert Green; Robert Bookman Wright; the late Syd Dernley; the Galleries of Justice, Nottingham; Inverary Jail Museum; Lincoln Castle; Ely Gaol; Moyses Hall, Bury St Edmunds; Ruthin Gaol; Walsingham Bridewell; Wymondham Bridewell; Norwich Castle; Essex Police Museum; and Helen Tovey at Family Tree Magazine . I would also like to thank my wonderful students and lecture audiences for their comments and interest in my research. Last, but by no means least, I thank my darling Molly and son Lawrence for their love, support and interest.

Unless credited otherwise, all images in this book are from originals held in the archive of the author.

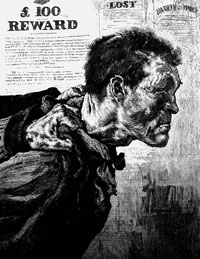

A Victorian villain and rough caught by the long arm of the law.

C ONTENTS

The long reign of Queen Victoria saw Great Britain ascend and acquire a global empire upon which it was said the sun never set. Britain led the world with industrial innovations and industry and those who lived in this noble country, the heart of the Empire, were left in no doubt of the expectations of them to honour Queen and Flag. Whether they were of the highest or lowest social class they were expected to uphold the law as a matter of duty it was just one of many Victorian values. There were, however, highly robust measures to keep you on the straight and narrow; woe betide you if you got caught breaking the law, for you would fall mercy to the Victorian criminal justice system, face exposure in the press and, potentially, a prison sentence.

Both the high and the low of society and all in between were, very much like today, liable to err and transgress the laws of the land, although it must be said the prison population of Victorian Britain was predominantly made up of those on the lowest incomes or with no job at all. Often the voices of these disenfranchised people are the silent majority, for they were often not literate enough to record their recollections of their time in prison. However, a dark mirror of their experiences can be assembled from the prison books maintained by the prison officials, the accounts of visitors to prisons or the experiences of prison staff especially the prison ordinary or chaplain that were occasionally published in periodicals or books; their stories often spoke of the most harrowing cases.

Her Majesty Queen Victoria.

The accounts of many trials were reported with zeal and, for the more horrific cases, lurid detail in the popular and local press; the more horrific the case, the greater the column inches and illustrations. Public interest would lead to follow-up stories of what the prisoner could expect in his or her prison. These stories give a fascinating insight into the working of the prisons, from uniforms and cells to the labour a prisoner or convict would be expected to undertake as part of their daily routine. Indeed, the extended accounts of prison visitors and some of the prisoners themselves have been reproduced verbatim and at length in this book.

The Victorian age was also one of enormous change and reform in the British prison system, with both good and bad results, but they were certainly far better than their gaoler ancestors at record keeping and reports, which often give a fascinating insight into the prisons of the day. Add to this the now rare, long out of print volumes and articles written by those who had experienced prison life first-hand as guardian, visitor or prisoner, as well as access to numerous unpublished manuscripts and letters, and a poignant picture may be assembled of the character, life and experience of the Victorian prison from both sides of the bars.

Neil R. Storey, 2010

Between 1837 and 1901 there were more than fifteen million receptions into the prisons of Great Britain. Those serving sentences in early Victorian prisons can be divided into two main categories. Firstly, there were those who had been tried and convicted of serious crimes and were serving their sentence in convict prisons administered by the Crown, such as the Kings Bench, Marshalsea and Fleet prisons (debtors prisons) and Newgate Gaol, or later in the national prisons such as Millbank or Pentonville, in Public Works prisons or by being transported (up to 1868). These men and women can truly be termed convicts and their long sentences were intended to reform their character. However, by far the greatest number of those behind bars were those on short sentences of less than one calendar month for minor felonies, who were imprisoned in their county, city or borough prison or gaol that were administered locally and were not, until 1877, the responsibility or property of central government. Those serving their sentence inside these were officially termed prisoners. Their experience of prison was intended to be a short, sharp shock to both punish the prisoner and provide a deterrence from future acts, rather than an attempt at reform.

Despite the high-profile visits and reports by prison reformer John Howard in the 1770s, which exposed the appalling conditions suffered by British prisoners, most of Britains prisons remained dank, unsanitary and verminous holes of misery until the 1830s, the only exceptions being the new-build prisons constructed under the Howard guidelines, such as Bury St Edmunds and Norwich City Prison.

New-build prisons that ignored Howards recommendations were those erected for the incarceration of French prisoners of war in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth century, such as Norman Cross (Cambridgeshire), Dartmoor (18069) and Perth (181012). Norman Cross was the first of these prisons, with work commencing in 1797, and was designed to hold between 5,000 and 6,000 prisoners. The site was surrounded by a perimeter fence and ditch and then divided into four quadrants, each containing two four-storey prison blocks that house up to 500 men sleeping in hammocks. Two regiments of soldiers were stationed in the barracks to guard the prisoners. It was known for the site to house over 7,000 men. By 1801 the conditions in which the prisoners were held had become a matter of public concern; they had insufficient clothing and instances of sickness such as fever, consumption, dysentery or typhus were often rife. There were a handful of escapes and in 1804 it was discovered that the prisoners had been involved in forgery after printing plates and related implements were discovered there. With some prisoners in a state of near nakedness, the British government provided prison uniforms of sulphur yellow colour in the hope these easily identifiable uniforms would prevent further escapes. Peace with France was declared in 1814 and all prisoners had left the garrison by June. By June 1816 most of the prison buildings were finally demolished. A total of 1,770 French prisoners of war had died at Norman Cross during their years of captivity.

Next page