BroadmoorRevealed:

Victorian Crime andthe Lunatic Asylum

Mark Stevens

SmashwordsEdition

Copyright Mark Stevens2011

This editionwas published electronically in summer 2011. Most of the storiescan also be read on the Berkshire Record Office website, www.berkshirerecordoffice.org.uk/albums/broadmoor .Comments and corrections are welcome: visit the Berkshire RecordOffice website and click on Contact Us.

MarkStevens

c/o TheBerkshire Record Office

9 ColeyAvenue

Reading

RG1 6AF

Mark Stevenshas asserted his moral right to be identified as the author of thiswork in accordance with the UK Copyright Designs and Patents Act1988.

SmashwordsLicence statement:

Thank you fordownloading this free ebook. Although it is a free book, it remainsthe copyrighted property of the author, and may not be reproduced,copied or distributed for commercial or non-commercial purposes.Thank you for your support.

Constructed inthe Smashwords Meatgrinder.

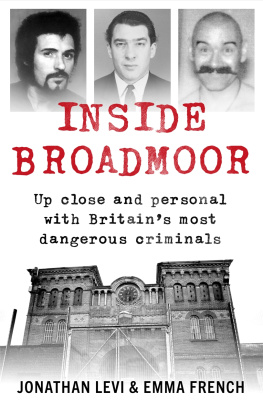

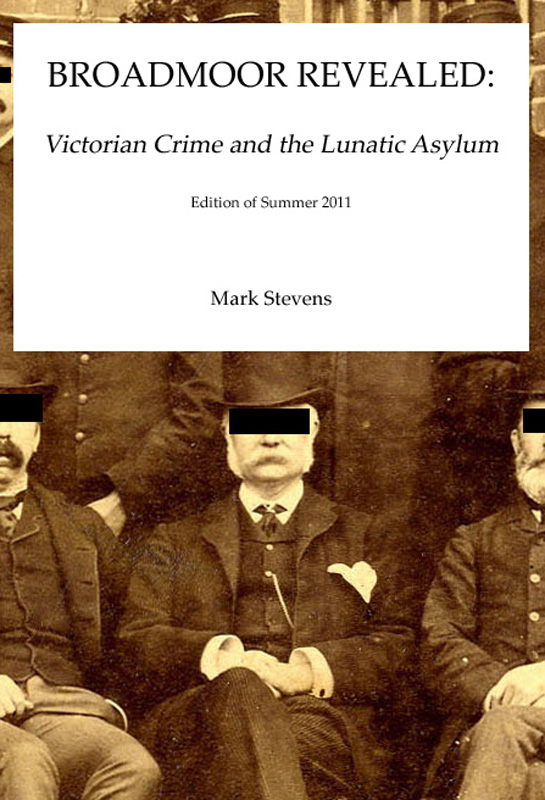

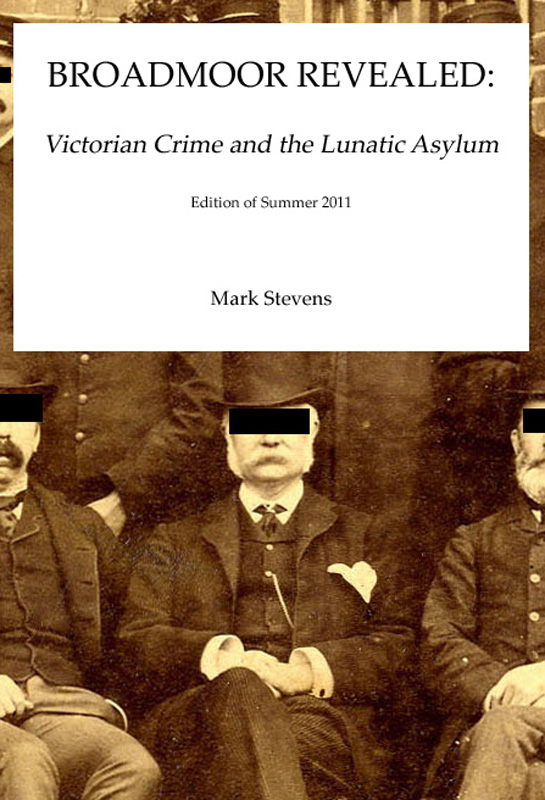

Front and rearcovers show a photograph of the male staff at Broadmoor, taken tocommemorate the retirement of Dr William Orange, 1886. Orange is inthe top hat in the centre of the front cover, flanked by hismedical staff. Berkshire Record Office reference D/H14/B6/1.

Contents

This shortcollection of stories grew from work to advertise the many personaltales contained in the archive of Broadmoor Hospital. When, inNovember 2008, the Berkshire Record Office made the archiveavailable for research, it was the first time that the generalpublic could access the historic collections of what was Englandsfirst Criminal Lunatic Asylum. As the person responsible forpromoting use of the archive, it fell to me to piece together somestories of the more well-known patients, with the idea that thiswould raise awareness of the fact that the archive existed, andgive researchers an idea of what they could discover about thepeople who spent time in the Hospital.

This was andis not always a straightforward task. As you might expect, a lot ofrestrictions for access remain on the archive. Particularly,patients medical records are closed for a considerable time. Thismeant that any publicity had to focus on the Victorian period, andso I began to put together brief biographies of those nineteenthcentury patients who are already part of public consciousness.Their stories are here: Edward Oxford, Richard Dadd, WilliamChester Minor and Christiana Edmunds.

However, thoseare only four patients out of over two thousand admitted before1901. They are also four patients about whom others have written,and about whom others are more qualified than me to write. So forme, the more interesting thing became how to tell some stories thatwere not well-known. There is no shortage of such material. Youcould choose virtually any patient and manage to bring somethingnew to our understanding both of Victorian England, and also aboutthe care and management of the mentally ill.

I chose acouple of things to write about as part of the Berkshire RecordOffice publicity. Firstly, I felt that the women of Broadmoorneeded to be heard, and that Christiana Edmunds was too unusual acase to be representative of that group. On the other hand, arepresentative female case would have to be a child murderer, andthis would potentially lack the redemptive element of the malestories of Oxford, Dadd and Minor, who were all remembered forachieving something despite their illnesses. Being a man, andtherefore impressed with all things maternal, I thought that agreat achievement of some female patients had been to give birthwhile they were in Broadmoor, so I decided that I could balance myinfanticide narrative by writing about the babies who came into theworld through the Asylum, as well as those who had left it.Secondly, I considered that I should not shy away from thenon-medical aim of the Asylum, that of being a place of publicprotection. Rather than dwell on tales of violence and rage, Ithought that a more entertaining way to highlight this would bethrough the concept of escapes. By writing about those that weresuccessful or otherwise, I thought that I might also be able todispel some of the preconceptions there might be about the dangersof an escaped lunatic.

So that thisbook has been put together from these individual pieces. As such,it is a tasting rather than a full bottle. In the longer term, itis my intention to complete another book about Victorian Broadmoor,which is planned as something different from a narrative history.The reaction to this short collection will give me an idea whethersuch a pursuit is worthwhile. There is so much I could tell youabout the place: but, for now, perhaps I had best let you readon.

MarkStevens

Reading,Berkshire

2011

On 27th May1863, three coaches pulled up at the gates of a recently-builtnational institution, which had been set amongst the tall, densepines of Bracknell Forest. Inside these three coaches were eightwomen and their escorts from Bethlem Hospital in London, theancient hospital for the treatment of the insane. It was now earlyafternoon, and that morning, the little party had left the Bethlembuildings in Southwark, boarded a train at Waterloo and been takenby steam through the capitals suburbs and out to the little markettown of Wokingham in Berkshire. Their destination was Broadmoor,Englands first Criminal Lunatic Asylum.

At half pasttwelve, they had alighted from the train at Wokinghams simplerailway station and found the three coaches waiting for them: alarger one, grandly-titled the Broadmoor Omnibus, together with twosmaller vehicles. These carriages would take them on the last legof their journey. The eight women and their accompanying paperworkwere loaded into the seats, before the steps were removed and thehorses started. Then the wheels of the coaches spun down windingearthy lanes and finally up a gentle incline as the passengers weredriven the five miles to Crowthorne. Broadmoors first patients hadarrived.

Who were thesewomen? As befitted a group thrown together without friendship, theyhad different backgrounds. One was a petty thief, for example,while another had stabbed her husband when they were out poaching.Then there were the other six, who had all shared a single lifeevent. They had killed or wounded their own children: eitherstrangling them, drowning them, or cutting their throats with arazor.

It was one ofthis last group who was the first patient to be listed in the newAsylums admissions register. Her name was Mary Ann Parr. She wasabout thirty-five years of age, and a labourer from Nottingham. Shehad lived in poverty all her life, almost certainly suffered fromcongenital syphilis, and had what we would now call learningdisabilities. Mary might have been just another member of theindustrial poor, except that when she was twenty-five years old,she had given birth to an illegitimate child and then suffocated itagainst her breast. She had been convicted of murder and sentencedto death, but her sentence was commuted first to transportation forlife, and then, after a medical examination, to treatment insteadin Bethlem.

When Mary AnnParr arrived at Broadmoor, as with every patient who would comeafter her, her details were first recorded from the forms that hadaccompanied her, and then she underwent a medical examination andan interview with one of the doctors. All the while, notes weretaken, and these notes were then written up into a large case book,and added to over the years. This is an extract from the notes madeabout Mary Ann Parr on admission: A woman of weak intellect,complains of pains in the forehead, short stature, cataract of theleft and right eyes can see a little with the left eye only.Teeth irregular and notchedOf very irritable temper.

Next page