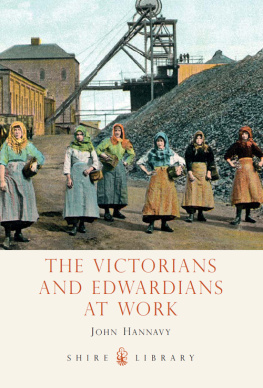

BRITAINS WORKING COAST

in Victorian and Edwardian Times

John Hannavy

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

CONTENTS

PREFACE

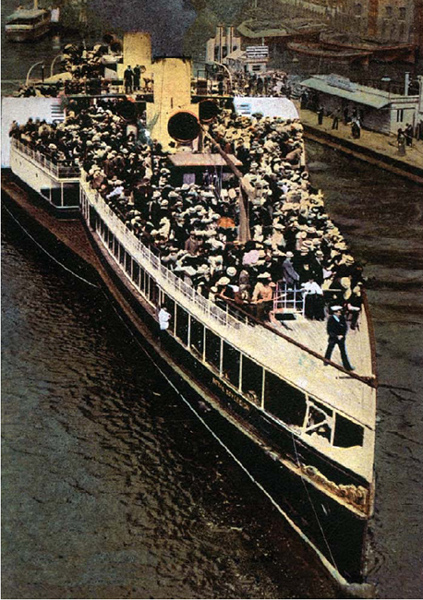

The PS (paddle steamer) Royal Sovereign is seen here leaving her London berth in 1903 in the days before the risks of such heavy overloading of steamers was considered an issue. Royal Sovereign was built on the Clyde by Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering Ltd in 1893 and had collapsible funnels to enable her to pass under London Bridge. She also boasted such luxuries as a barbers shop, a bookstall and toilets.

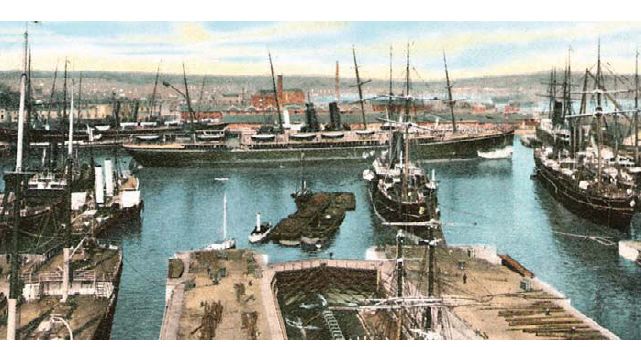

This busy view of The Approach to Newcastle was photographed by Alfred D. Miller in 1905.

The idea for a follow-up to my 2003 book The English Seaside in Victorian and Edwardian Times has been with me for several years now and has taken some time to realise. This new collection is more about the people who lived and worked along the coast the jobs they did, the places in which they lived, and the impact their endeavours had on Victorian and Edwardian Britain. Having set these restrictions, and made a firm decision not to duplicate anything from the earlier book, I found that pictures suitable for inclusion in Britains Working Coast in Victorian and Edwardian Times proved much more difficult to track down. So I owe a great debt of thanks to the dealers and friends who located cards for me or brought them to my attention as is always the case, many people make a valuable input into the creation of any book, despite the prominence of the authors name on the cover.

All the images come from my own collection except one (on ), and for that I thank Ben Norman of Watchet, who shares my enthusiasm for the work of James Date.

It is a testament both to the many photographers whose work is illustrated here, and to the Edwardian postcard collectors who kept their treasured cards safely, that we have such a rich visual account of life in the mid to late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century. As a result of their enthusiasm for recording the ordinary and the everyday with such perceptive eyes, they have passed down a legacy of pictures especially the coloured ones through which the Victorians and Edwardians seem just that much closer to us in time.

John Hannavy, Great Cheverell, 2008

INTRODUCTION

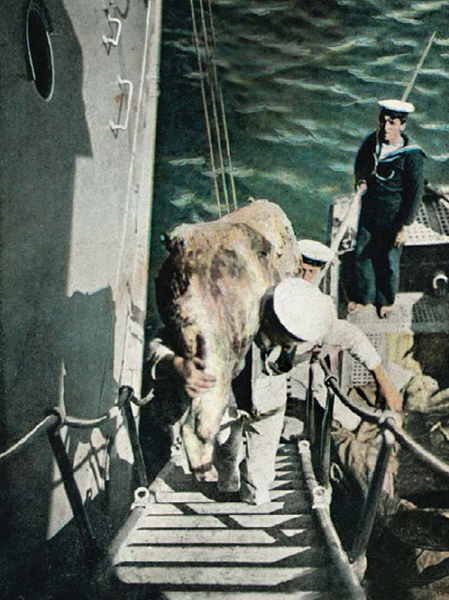

The exact location of this 1904 scene, entitled Royal Navy No. 4 Meat Coming on Board, is not known, but it is from a series of postcards many of which were photographed in and around the Portsmouth area.

Since the middle of the eighteenth century medical opinion had been actively promoting the health advantages of visiting the seaside breathing in the fresh and bracing sea air instead of the pollution that hung permanently over the inland industrialised towns and cities. Pivotal in this movement was Dr Richard Russell, whose advocacy of the health benefits of taking the plunge into sea water is credited as being one of the moving forces behind the establishment of Brighton as a seaside resort.

Yet this advice ignored the fact that the coastline itself was becoming increasingly industrialised, with the same attendant problems of pollution and overcrowding. As Britain increasingly ruled the waves both in naval and commercial terms and depended on its coastal ports for its increasing import and export trade with the rest of the world, it was in many cases a simple exchange of the smoke, noise and effluent of inland factories for the smoke and noise of steamers, railways, shipyards and a host of other manufacturing industries which relied on those ports for their existence.

Great cities such as Liverpool, which had been relatively small towns before the Industrial Revolution, expanded rapidly throughout the nineteenth century, attracting workers in their tens of thousands as industry spread along the strip of land with easy access to the waterfront.

Shipyards lined the Mersey, the Thames, the Tyne and the Clyde as demand grew for more and larger steamers to transport the goods of the Empire home to Britain, and to export the countrys huge manufacturing output to the rest of the world.

In the days before refrigeration, preserving the huge catches of herring was of primary concern. Pickling the fish in barrels of brine was the simplest and most reliable method available, providing employment for thousands in the barrel-making industry around the coastline.

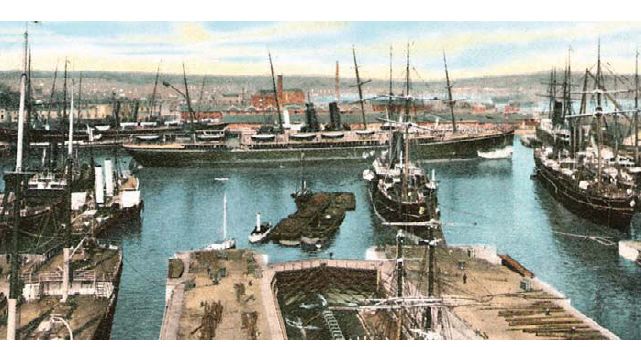

Within the span of the nineteenth century, Southampton Docks (seen here in 1902) grew from an idea into one of the largest and most successful dockyards in Britain, employing thousands of people. From the establishment of a pier and harbour commission in 1803, and the construction of the Royal Victoria Pier in 1831, the docks were almost continuously expanding. Taken over by the London & South Western Railway in 1892, the docks became part of an integrated cargo-handling and transport system which enabled manufactured goods to be taken rapidly from factory to ship, and imported goods from ship to distributor. Directly and indirectly, these huge docks sustained the livelihood of tens of thousands of people throughout southern England.

Traditionally, fishing had long been the major coastal employer. With the profusion of herring, especially in the North Sea, the fishing industry grew throughout the nineteenth century, peaking in the last decades.

The associated industries of boatbuilding, barrel-making, ships chandlers, sail- and net-making and wholesale fish markets all grew to keep up with demand, employing ever more people.

Railways reached most coastal ports in the middle of the nineteenth century, offering faster delivery of the fish to the markets of the great cities.

However, during the nineteenth century, industrial manufacturing concerns overtook fishing as the major source of employment in many places. The population growth in many harbour towns during the second half of the century was rapid and considerable. Ever larger ships required ever larger docks, which employed more and more stevedores to handle the huge increases in cargo being imported and exported.

By 1900 tourism had pushed fishing into third place. The introduction of fast passenger railway services and statutory holidays made travel to the coast easier and, by the late nineteenth century, had brought a visit to the seaside within the reach of an increasingly large proportion of the population. Thus in many coastal towns the leisure industry developed as a source of employment alongside heavy industry, while elsewhere one or the other dominated. Indeed, the first passenger-carrying railway was developed out of an industrial railway as early as 1806 long before horse-drawn rail travel gave way to steam. That first passenger-carrying railway from Swansea to Mumbles in south Wales was responsible for the development of the village into a tourist resort, offering a pleasant day out from the industrial landscape of Swansea. Benjamin French, who first proposed that passengers could be carried by rail, remains one of the great unsung heroes of the travel revolution. So popular was his railway that before the end of the century double-decked carriages were needed to meet demand.