THE VICTORIANS AND EDWARDIANS AT WORK

John Hannavy

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The idea of compiling a book about the Victorians and Edwardians at work has been with me for several years, and it is especially pleasing to see it come to fruition. With its companion volume The Victorians and Edwardians at Play, it commemorates a period when first the photographic print, and later the picture postcard, were the media through which British life was defined and celebrated.

As with every book I have produced over the past thirty-five years, although it is my name on the cover, the project is not the work of the author alone. It depends for its interest on the knowledge and input of many local historians and collectors who can add context and colour to the story each of these images has to tell us. My own collection of Victorian and Edwardian images built up over more than thirty years of searching auction houses, flea markets, antique shops and junk shops is the source of the majority of the pictures. I owe a growing debt of gratitude to the friends and dealers who continue to bring exceptional images and collections of pictures to my notice, and to the many people who have answered my questions about the images on these pages. The images from my own archive are augmented by a small number from the collections of the late Ben Norman, David and Marilyn Parkinson, Ron Callender, and the Ashbee-Gray-Lambert Collection. I am grateful for their generosity, and my thanks go also to Michael Gray and Alistair Gillies for their help and support.

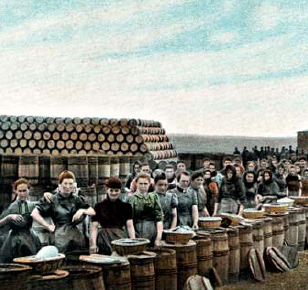

Colour is the great thing in so many of these pictures we are so used to seeing the past through monochrome or sepia photographs that to experience the Victorian and Edwardian world brought to life in these remarkable tinted images seems somehow to bring us a little closer to that world.

John Hannavy, Great Cheverell, 2008

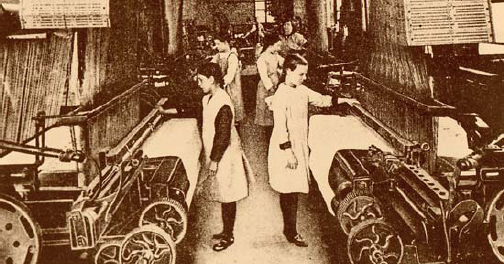

In this picture, children are being trained in the Bolton cotton mills of John Kershaw & Sons. The employment of children as young as twelve was commonplace until outlawed in 1918.

INTRODUCTION

William Henry Fox Talbot: Woodmen, Lacock, from a calotype negative probably exposed in the summer of 1845. The subjects were carefully posed to enable them to keep perfectly still for the long exposure, yet still retaining a sense of animated activity.

Taking photographs of people at work is an application of the medium that is almost as old as photography itself. The first practical photographic processes date from the late 1830s and the very early 1840s. Both the French daguerreotype and the British calotype process came to public notice around that time, and the inventors and promoters of both were keen to demonstrate their versatility and usefulness.

The daguerreotype process produced a direct unique positive image on a small, silvered copper plate, highly detailed and as unique as a miniature painting, while the calotype produced a paper negative from which countless prints could be made. It was the calotype that proved to be the system from which photography would develop, but in the early days the promoters of both methods were keen to demonstrate the versatility of their respective processes.

Thus it was, probably in 1845, that the inventor of the calotype paper negative process, William Henry Fox Talbot, created the first planned occupational photographs when he turned his crude wooden camera towards the woodmen who worked on his estates in Lacock, Wiltshire. Earlier, a shoe-black had been photographed inadvertently in a Paris street in the late 1830s he and his customer being the only living beings to remain still throughout the long exposure but Talbots pictures of his woodcutters were planned and carefully composed, the workmen positioned to convey a sense of animated activity while adopting poses they could hold still for a long period of time. Only one thing undermines the importance of this picture as the first of a genre: the subjects were not woodcutters at all, but Talbots assistant, Nicolaas Henneman, on the left, and his groom, Samuel Pullen, on the right. What Talbot initiated, others developed into one of the most important uses of photography giving history a priceless visual record of the Victorians and Edwardians at work.

As exposure times shortened through the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s, photographys ability to capture the real activity of people at work improved immensely. The camera went to war for the first time in the 1850s: Roger Fentons pictures from the Crimean War in 1855 are icons of early photography, although many of his pictures were of carefully posed groups.

The Manchester Ship Canal at Eastham, c.1900, published as a postcard before 1904. The three locks at Eastham marked the meeting of the canal and the River Mersey. In this view, a steamer is just about to enter the largest lock on her way out of the canal, while a sailing vessel waits her turn. The canal had opened six years earlier, in 1894, and, with the extensive docks constructed in Salford, had brought great prosperity to Manchester. So successful were the docks that the half-mile-long No. 9 dock, built on the site of Manchester racecourse, opened in July 1905.

Great industrial projects were photographed showing men at work constructing the great bridges, ships and railway locomotives that drove Britains development throughout the nineteenth century.

The popular process throughout much of that period was the wet collodion glass-plate process a cumbersome process, and anything but user-friendly, but one which yielded the highest-quality images photography had yet delivered. The need to prepare and coat the large glass plates just before they were exposed in the camera, and to develop them immediately afterwards, required the photographer to take a portable darkroom with him wherever he travelled. Some highly ingenious designs for portable darktents were patented and advertised widely in the photographic press.

Roger Fentons photographic van on location in Wales. As the collodion process required the plate to be coated with light-sensitive chemicals just before use and processed immediately after exposure, a portable darkroom was essential. Fenton travelled extensively throughout Britain with the van in the 1850s.

A young man poses in front of an early steam trawler in Grimsby docks.