THE VICTORIANS AND EDWARDIANS AT PLAY

John Hannavy

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

CONTENTS

PREFACE

The idea of compiling a book about how the Victorians and Edwardians spent their leisure time has been with me for several years, and it is especially pleasing to see it come to fruition. With its companion volume The Victorians and Edwardians at Work, it celebrates a period when first the photographic print, and later the picture postcard, were the media through which British life was defined and celebrated.

As with every book I have produced over the past thirty-five years, although it is my name on the cover, the project is not the work of just the author. It depends for its interest on the knowledge and input of many local historians and collectors who have added that little bit of context and colour to the story each of these images has to tell us. Once again, my own collection of Victorian and Edwardian images built up over almost forty years of searching auction houses, flea-markets, antique shops and junk shops is the source of the majority of the pictures.

I owe a growing debt of gratitude to the friends and dealers who continue to bring exceptional images and collections of pictures to my notice, and to the many people who have answered my questions about the images you see on these pages. It is the information in the text and captions that really brings these pictures to life, and that has been generously shared by the many collectors and historians whose expertise has expanded my own knowledge.

Colour is the great thing in so many of these pictures we are so used to seeing the past through monochrome or sepia photographs, that to experience the Victorian and Edwardian world brought to life in many of these remarkable tinted images, seems somehow to bring us a little closer to that world.

John Hannavy, Great Cheverell, 2008

A group of children walking and playing on the Fish Quay at Blyth, Northumberland, c.1900. Typical of children of the period, despite the fact that they seem to be dressed in their Sunday best, all but one of the girls are barefoot.

INTRODUCTION

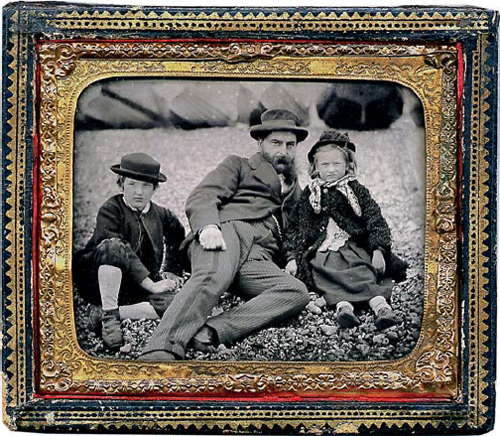

This 1/6th plate ambrotype a direct positive image on glass was taken by an unknown itinerant beach photographer in the 1860s or early 1870s. Travelling photographers used cameras with internal processing which meant that the picture could be developed in a tray of chemicals at the bottom of the camera, the plate being manipulated by the photographer through light-tight arm holes. Such cameras meant that the photographer could travel and work anywhere without needing all the paraphernalia of a portable darkroom or darktent.

The whole idea of leisure time and leisure pastimes was, for the majority of people at least, a hard-won privilege unheard of before the nineteenth-century reforms of employment rights. Hitherto, such indulgences were the exclusive domain of the wealthy. Even photography itself was originally practised only by those with unlimited time and a deep purse the first amateurs to travel with their cameras were land-owners, doctors, lawyers and the like.

It would be late in the Victorian era before the masses could afford to visit a photographer, and the early twentieth century (the box camera revolution) before they could afford to create their own mementoes of their leisure time, their holidays and their sporting enthusiasms.

Ironically, even the humble peasant had enjoyed more free time to pursue simple pleasures in medieval Britain than was available to the majority of workers at the beginning of the Victorian era. As will be seen elsewhere in this book, laws were passed in the fifteenth century to try and curtail the amount of time archers were spending playing golf. Four centuries later, the vast majority of people had neither the time nor the money for such indulgences!

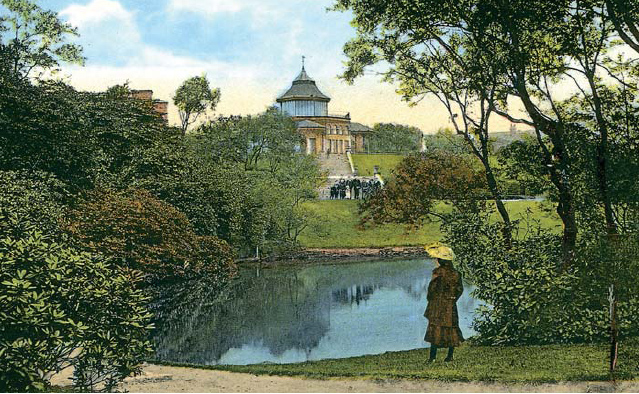

A young girl looks across the serpentine lake in Wigans Mesnes (or Meynes) Park in 1905, towards a group of youths standing at the foot of the steps leading to the pavilion. Parks like this (Mesnes Park was created in 18778) were established in many towns throughout the country, funded partly by local authorities and partly by local mill, factory and colliery owners. In 1889 Wigans showpiece park was described as one of the lungs of the town, a breathing spot for the thousands who, for most of their time, are cooped up in factories, collieries &c& and in the spring and summer, Meynes Park presents a pretty sight.

With no money to travel, and with limited free time anyway, the local park became a key component of the lives of working people. Local authorities, often prompted by generous endowments from local employers and landowners, developed beautiful municipal parks in most towns and cities, often with a pavilion, and invariably with a bandstand where local factory or church bands would perform on a Sunday afternoon.

All the parks had elaborate gardens, many had small serpentine lakes, and all were furnished with strategically positioned benches from which to enjoy the views.

Armies of gardeners and park attendants maintained and ruled these small patches of green in the midst of grim industrial urban areas. Their rules were published at the park gates, and those who ventured into their local parks understood and accepted that their demeanour and their behaviour had to conform. Walking or sitting in the park may have been a leisure activity, but it was still subject to accepted standards and disciplines.

One of the first crazes of the photographic era was collecting and viewing 3D or stereoscopic images. From the late 1850s, every Victorian drawing room had a stereoscopic viewer some of them simple hand-held devices, others elaborate pieces of furniture. New stereocards were published weekly, and were available through local print-sellers and photographic studios. The Stereoscopic Magazine in the early 1860s brought some remarkable 3D images to the notice of the public, albeit at a price that placed them beyond the budget of many. The London Stereoscopic and Photographic Company published hundreds of cards, many of them in large sets, covering subjects that ranged from educational views of different parts of the world being very popular to pure entertainment.

Genre cards included subjects ranging from historical re-enactments to humorous situations such as party games. Many of these images were later cropped down to the cartede-visite size print, which became the ubiquitous format of the 1860s and fitted the standard Victorian family album.

Lantern slide lectures were another popular entertainment. Village halls, church halls and assorted other locations were filled with people keen to hear stories from intrepid travellers who had journeyed to far-flung corners of the world.