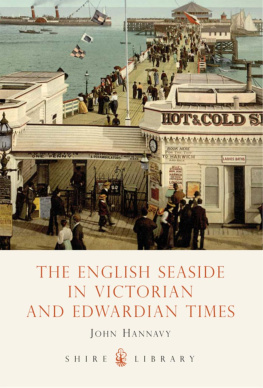

The English Seaside

in Victorian and Edwardian Times

JOHN HANNAVY

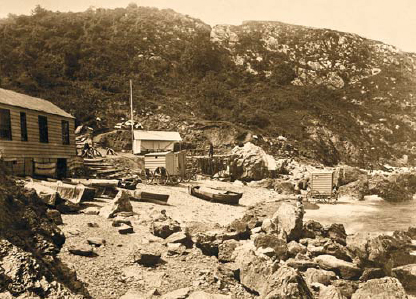

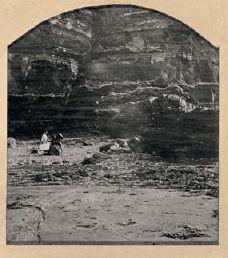

Alum Bay and the Needles, c.1870. Idyllic views like this did a great deal to popularise the idea of a seaside holiday offering the promise of a gentle unhurried lifestyle away from the bustle of the town.

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

Contents

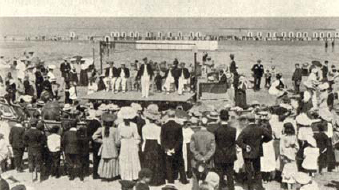

A group of travelling pierrots on an unidentified beach on Englands east coast in August 1906. In the distance is a line of bathing machines with their attendant horses and handlers.

Acknowledgements

The images contained in this book were taken by a great many Victorian and Edwardian photographers some well-known, others anonymous. Their work graced Victorian family albums throughout the land, and an even larger number of Edwardian postcard albums.

While the book contains many sepia images from 1860 onwards, and coloured postcards produced between 1902 and 1910, it is enriched by a rare and little-known collection of coloured photo-lithographic prints photographed and printed in the closing years of the nineteenth century by the Photochrome Company, originally from Zrich but with a London office from the mid 1890s.

No book is ever simply the work of the author, and this is no exception. My thanks, therefore, go to the many people throughout England who have answered my many questions by letter, email and telephone about the pictures and the locations. It is their knowledge of local history which has brought these images to life. With very few exceptions, the illustrations all come from my own collection. In many cases the originals have been digitally cleaned and enhanced to restore their quality. Thanks are due to Marilyn and David Parkinson, and to the many dealers and collectors who have brought exceptional and unusual images to my notice over the past thirty years. Thanks also to those readers who helped me identify the unidentified pictures in the first printing.

John Hannavy, Great Cheverell, 2008

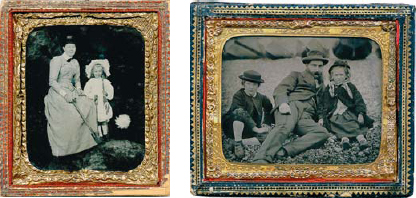

These 1/6th plate ambrotype images from the 1870s, taken in Yorkshire (left) and Dorset (right), were created by unknown travelling beach photographers. These unique direct-positive images on glass the instant pictures of their day were processed inside the camera while the subjects waited.

Introduction

Photography and the seaside summer holiday grew up together. Both achieved huge popularity during the first half of the nineteenth century, and both enjoyed their heyday in the years before the First World War.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that photography captured the magic of the Victorian and Edwardian seaside holiday in all its glory from the simple beach portraits produced by the itinerant photographers of the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s, through to the sophisticated multicoloured lithographs which were sold in the 1890s as being real colour photographs.

These Photochromes are what you see on many of the pages of this volume, the direct predecessors of the colourful picture postcards with which we have all grown up. By the time the nineteenth century came to a close, photography was on the verge of becoming the popular hobby it has been ever since.

It would be quite wrong, however, to imply that the seaside holiday was a nineteenth-century invention. Enthusiasm for breathing the pure clear air of the seaside developed in the early eighteenth century, simultaneously at several points around the coast. Indeed, beach huts made their appearance in the early 1730s. Beach huts on wheels fore runners of the ubiquitous Victorian bathing machine ap peared on Scarborough beach in North Yorkshire before 1735, while the bathing machine itself, the invention of one Benjamin Beale, first appeared on Margate beach around 1750.

Ansteys Cove, Torquay, 1870s, a scene which changed very little in the following thirty years see .

1750 was a pivotal date in the development of the seaside holiday. Medical opinion at the time began to expound the therapeutic virtues of sea air, and of both bathing in and drinking seawater taking the seaside cure. For that idea, credit, if such it deserves, goes to several people, including Sir John Floyer and Dr Richard Russell, the latter of whom is also credited with being the primary moving force in the establishment of Brighton as a popular seaside resort. Public enthusiasm for the beneficial value of the seaside was spurred in the 1780s by its obvious endorse ment by the Prince of Wales, later King George IV, who took up residence in Brighton.

Beales original bathing machine was a much more elaborate idea than the one which appears in many of the beach scenes in this book. For example, it had a huge canvas hood which could be brought out to cover the area between the end of the machine and the surface of the water allowing bathing in complete privacy. As one late-eighteenth-century guidebook explained, by the use of this very useful contrivance, both sexes may enjoy the renovating waters of the ocean, the one without any violation of public decency, the other safe from the gaze of idle or vulgar curiosity. It is hard to relate such self-consciousness with a freely enjoyed holiday pastime. But the formality of the dress codes evident in so many of the pictures in this book and they cover the period 1860 to 1910 challenges whether or not the full pleasures of a relaxing seaside holiday could ever have been enjoyed by the participants.

Even bathing, apparently, had to conform to conventions and timetables! In an August 1851 edition of his own magazine, Household Words, Charles Dickens wrote a delightfully perceptive essay on the seaside holiday, primarily about his home town of Broadstairs but applying to so many other expanding resorts. He wrote:

Enjoying the sun beneath the Alabaster Cliffs, Watchet, Somerset, summer 1862. This image is half of a stereoscopic ambrotype, an early three-dimensional picture, taken by local photographer James Date, whose studio was only a few hundred yards away. Nevertheless, because the plates had to be coated with their light-sensitive chemicals just before the picture was taken, and then developed immediately after exposure, Date would have had to take a portable darkroom tent with him and pitch it on the beach close to his camera.

So many children are brought down to our watering place that, when they are not out of doors, as they usually are in fine weather, it is wonderful where they are put; the whole village seeming much too small to hold them under cover. In the afternoons, you see no end of salt and sandy little boots drying on upper windowsills. At bathing time in the morning, the little bay re-echoes with every shrill variety of shriek and splash after which, if the weather be at all fresh, the sands teem with small blue mottled legs. The sands are the childrens greatest resort. They cluster there, like ants: so busy burying their particular friends, and making castles with infinite labour which the next tide overthrows, that it is curious to consider how their play, to the music of the sea, foreshadows the reality of their after lives.