In a world of high-speed travel and communications, advanced medical science and multi-media entertainment at the touch of a button, it is hard to conceive of a life where it was not unusual for country dwellers to pass a whole lifetime without leaving their native county. A great gulf separated the rich and the poor. For the wealthy, it was a life of comfort, with every whim attended to, while the poorest suffered almost unimaginable deprivation.

At the start of the twentieth century, life moved at a slower pace the rich had carriages or, increasingly, cars. The poor went on foot, walking miles to work before a day in the factory, the mine, the mill or in the fields. The picture was the same throughout the country.

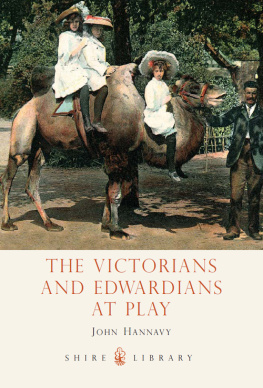

For country people the big excitement was the arrival of a travelling fair, or the annual one-day holiday for the works outing perhaps to the seaside. In cities there were the raucous music halls, while the earliest cinemas were showing glamorous silent films. With no television, radio or recorded music, people were forced to make more of their own entertainment. The changing seasons brought traditional festivals and celebrations, while children displayed extraordinary ingenuity with their playground games.

Work or the lack of it was a key factor in the family's survival, and an industrial illness or injury to the breadwinner could be devastating. Children officially left school at the age of fourteen often after a spell of working split days where they went to school in the morning and to work in the afternoon but in big families, the oldest child would often have to start work even younger to support the growing numbers. For those with no family and no work, the spectre of the workhouse still loomed.

Working-class communities were close-knit tenement dwellers in the cities and rural villagers alike and in times of adversity or illness, neighbours rallied around. Where a doctor or midwife cost money that the family could ill afford, it was not unusual for a local woman to deliver babies, sit with the dying and lay out the bodies often for no payment.

It has been my pleasure to meet a number of men and women who were born before and during the Edwardian period, the oldest being Henry Allingham, who is now 109. Their stories, along with those of many other ordinary people that have been recorded over the last forty years by a range of voluntary groups, archives and institutions, create a unique glimpse into an age which is now almost entirely beyond our reach. The length of the accounts I have chosen vary, some take many pages, whereas others simply select the most affecting moments. Most contributors appear only once, while others you will see several times. It has been a privilege to listen to the voices of these men and women, many now long dead, and to bring together their vivid memories. These are their words I have been but a catalyst.

Max Arthur

London

January 2006

PROLOGUE

END OF AN ERA

Jim Davies

We lived in Windsor and I used to see Queen Victoria quite often on her terrace with her two Indian attendants. I suppose I was four years old. My father was a great patriot, but to me she was an old woman in a black bonnet.

Kitty Marion

On 22 January 1901, the manager of the Opera House, Cheltenham, announced to the audience the news of Queen Victoria's death. People listened and quietly dispersed. It seemed as if the world stood still and could never continue without the Queen. However, the following day King Edward VII was proclaimed King and life went on as usual.

Arthur Harding

It was the most extraordinary thing. Everybody the children as well wore black. Everyone was in mourning. Even poor little houses that faced onto the street put a board up and painted it black. All the shops had black shutters up and everyone felt as if they'd lost somebody. It was extraordinary that people who were starving for the best part of their lives should mourn the old Queen. I was a bit of a rebel and I couldn't really understand it.

Clement Williams

In 1901 I was in the Oxfordshire Light Infantry and I was present at Queen Victoria's funeral. The day was bitterly cold. It was snowing hard and we had to leave Oxford at five o'clock to get there in time. We caught the train, but there were no heated carriages in those days. When we arrived at Slough, seeing that we had plenty of time in hand, our commanding officer sent us on a twelve-mile march to warm us up. We marched into Windsor, where we were given a tin mug of beer and a pork pie. Then we stood about and waited until the ceremony began. We lined the route to St George's Chapel but we had nothing to do because the crowds weren't allowed there. It was very interesting to see Queen Alexandra, the Prince of Wales and the two little boys in sailor suits, as they arrived. Trouble began when the coffin arrived on the train. The coffin was supposed to be placed on a gun carriage to be pulled to the castle by horses. The train was late and the day was cold, but with the excitement of all the comings and goings, the horses simply wouldn't move. They didn't like it and were jumping and kicking about, and looked as if they were going to upset the whole thing, so they were taken out of their harnesses. The carriage was supposed to be followed by a Naval Guard of Honour, and a naval officer came forward and suggested that his men be put in place of the horses. The sailors were harnessed onto the gun carriage and they hauled the coffin up the hill right the way up to the castle. Of course, it took them a long time to pull the carriage all that way, and in the meantime, everyone was waiting. We knew by the salute guns that the coffin must have arrived at Windsor, but it was taking a long time to reach the castle. Time went by and I saw Earl Clarendon, the chap in charge of the ceremony he kept coming out and looking down the road, wondering why nobody came. You could hear a band in the distance but nothing was happening. Then Queen Alexandra came tearing out, looking this way and that way, before Clarendon persuaded her to go back into the Chapel. Finally, the carriage came along very slowly, hauled along by the Navy. After the ceremony, King Edward VII appeared on the steps of St George's Chapel. He stood with the Kaiser and we gave them the royal salute. They saluted us back. Then they went off and we packed up and went home.

Nina Halliday

We saw the procession from a stand which had been erected under the Guildhall. The seats were covered in black material and everyone wore black clothes, but I had a dress, coat and hat of a lovely mauve colour I loved it. The streets were lined by Foot Guards and the pavements were packed tight with people all dressed in black. It was a long wait, as the train bringing the coffin and all the important people travelled very slowly from Paddington to Windsor so that people at the stations which it passed could see it.

It was a wonderful procession, with the Life and Foot Guards playing the Dead March. The Guard of Honour led; then came the gun carriage covered by the Royal Standard. The new King, Edward VII, followed with many of the Queen's relations and Kings and Princes all in uniform. The finest was the Emperor of Germany in a beautiful white uniform and white helmet with lots of gold on it, and many Orders and decorations. Then came the chiefs of the Navy and Army and members of the Queen's Household, followed by members of the Queen's Court, including her daughters and other relations in royal carriages all, of course, in black with long veils.