Copyright

Copyright 2019 by Kristina Seleshanko

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

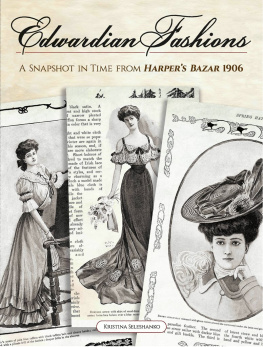

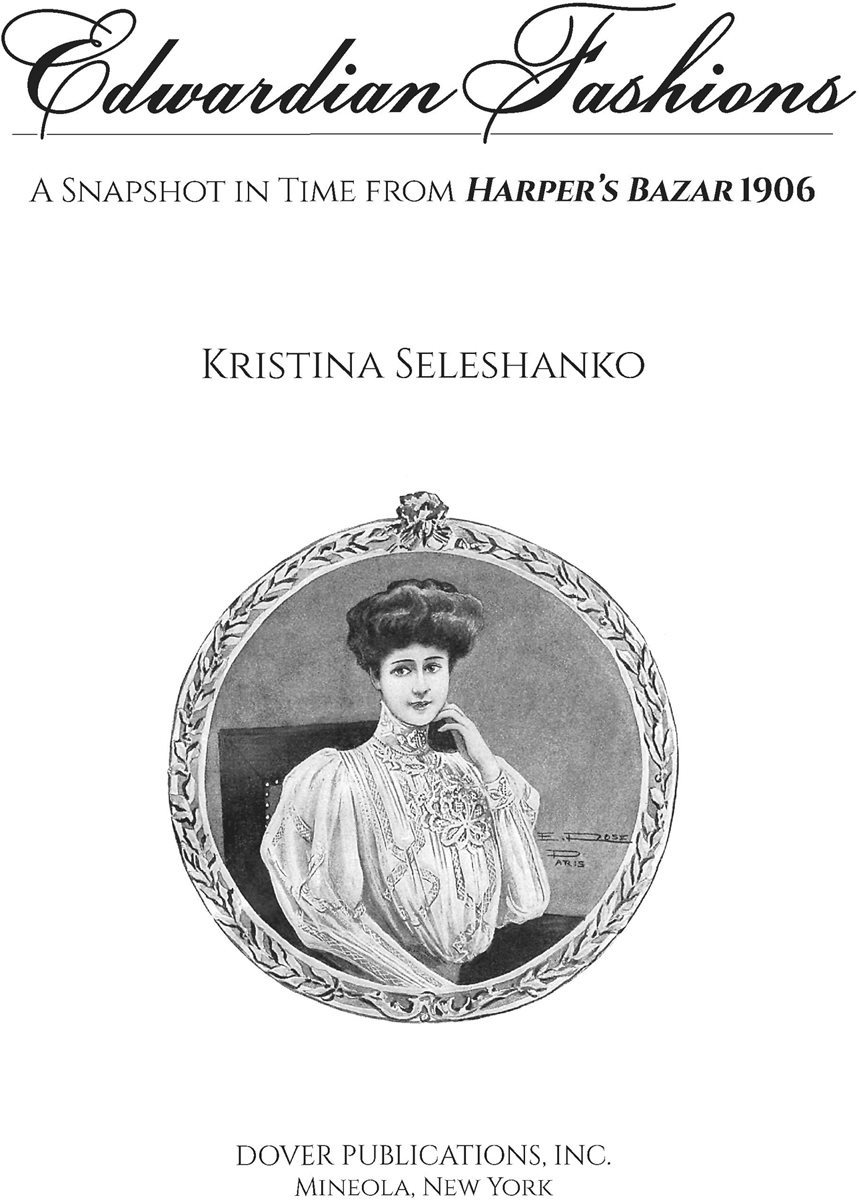

Edwardian Fashions: A Snapshot in Time from Harpers Bazar 1906 is a new work, first published by Dover Publications, Inc., in 2019. This book contains text and illustrations originally published in Harpers Bazar, published by Harper & Brothers, Publishers, New York, in JanuaryJune 1906.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Seleshanko, Kristina, 1971 author.

Title: Edwardian fashions: a snapshot in time from Harpers Bazar 1906 / Kristina Seleshanko.

Description: Mineola, New York: Dover Publication Inc., [2019] | Summary: From spring hats and fancy aprons to French evening gowns and bridal attire, these authentic magazine illustrations offer a glimpse of American values at the turn of the 20th centuryProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019015948 | ISBN 9780486837239 (trade pbk.) | ISBN 0486837238 (trade pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Clothing and dressGreat BritainHistory20th century. | Clothing and dressFranceHistory20th century. | Harpers bazaar.

Classification: LCC GT738 .S45 2019 | DDC 391.00941/0904dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019015948

Manufactured in the United States by LSC Communications

83723801

www.doverpublications.com

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

2019

CONTENTS

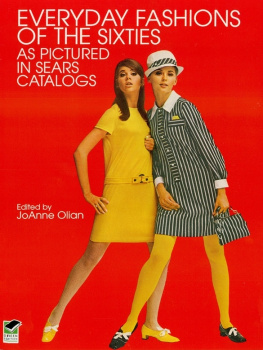

Part One: Everyday Fashions

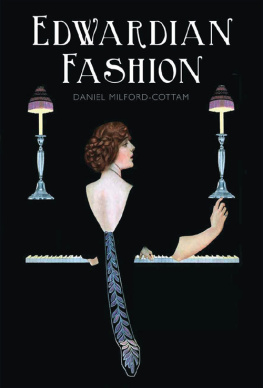

Part Two: Seasonal Fashions

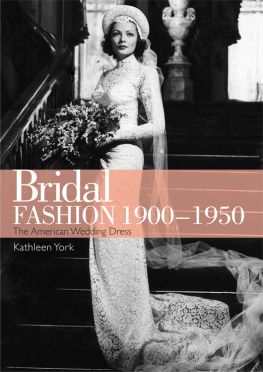

Part Three: Special Occasions

Part Four: For the Young and Old

INTRODUCTION

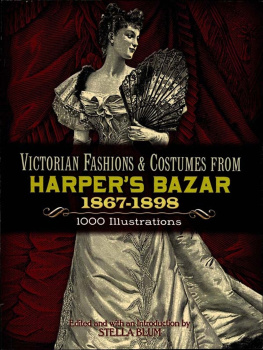

A repository of fashion, pleasure, and instruction is how the publishers of Harpers Bazar described its first issue. It was 1867, and the newspaper-like publication cost just 10 cents an issueor $4 a year. At that time, Bazar was spelled with just one a. The more familiar double a wasnt added to the magazines title until 1929.

Fletcher Harper deserves the credit for setting Harpers Bazar apart from every other periodical of the era. Since the early part of the nineteenth century, womens fashion magazines such as Godeys Ladys Book, Petersons Magazine, and Mirror of Fashions flourished. Yet Fletcher spotted an audience he didnt feel other magazines properly targeted: well-to-do women. His familys publishing company was already well-established in the field of books; they also published the literary Harpers New Monthly and Harpers Weekly periodicals. But Fletcher thought he could transform the fashion magazine industry with a singular idea: He believed wealthy American women wanted to see the latest fashion trends at the same time women in France, England, and Germany did.

This may not seem like a revolutionary idea now, but in the 1860s, American magazines did not publish anything in the way of truly original fashion art. Instead, they copied European fashion drawings, with artists watering down those elite designs so theyd be suitable for average American readers. It took monthssometimes up to a yearfor American magazines to showcase these fashions. Even though style changes took a dawdling pace in the days before television and the internet, once fashions appeared in mid-nineteenth-century American periodicals, they were already pass in Europe.

To change that, Fletcher sourced the German periodical Der Bazar, making a legal agreement with its publisher. Now Der Bazars fashion plates would premiere simultaneously in Harpers Bazar.

Fletchers timing was perfect. The Industrial Revolution had created more wealth than the United States had previously known. Harpers Bazar not only gave the resulting multitude of wealthy women easy access to the latest fashions, but it also proffered advice on how to live in their affluent New World.

To head up his progressive magazine, Fletcher Harper chose Mary Louise Booth, an extraordinary thirty-six-year-old woman. Fluent in Latin, French, and German, shed taught school at age fourteen and then became a vest maker to support herself while pursuing a writing career. At first, most of her written work was published without pay, but in 1857, she became one of the first female journalists for The New York Times. In 1862, Booth drew national attention, including praise from President Abraham Lincoln, for her translation of the French antislavery tract The Uprising of a Great People: The U.S. in 1861. Booth was also a womens rights activist, working alongside Susan B. Anthony to obtain the vote for women. Newly installed as editor of Harpers Bazar, Booth lined up writers such as Charles Dickens, Henry James, and George Eliot to provide literature for the publication. She installed the founder of La Mode Illustre, a popular French fashion journal, to become the magazines Paris correspondent. And politics? Booth made sure they were not off-limits either. Harpers Bazar was one of the first popular periodicals to support the education of women and womens suffrage.

1906: Royal Obsessions

By the early 1900s, Americans were ever-discussing the new place women held in the world: without the vote, but with far more opportunities in business and private life than American women had experienced before. The editorial commentary and fashions showcased in Harpers Bazar reflected this. In addition, the magazine bestowed an inordinate amount of space to European royalty. Although this might seem strange given the magazines target audience of Americans, it may also feel familiar to todays magazine readers.

Americas Obsession with Royalty Started with Princess Diana, The New York Times boldly stated in 2012, but in reality, our obsession began with the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) way back in 1860. Greeted by happy throngs as he traveled in Detroit, Chicago, Albany, D.C., and elsewhere, the young royal thrilled Americans. The Prince was regal. He was youthful. He was cheerful. He was differentso differentfrom his old-fashioned mother, Queen Victoria. He was modern.

It was the first time any British royal had set foot on American soil.

The American experience of the British royal family is like observing someone elses children, Victoria Penate wrote in a 2018 article for The Bottom Line. They capture the most attention from us when they do something cutein the royals case, hold an ornate wedding featuring extravagant hats or exercise intense care in dressing their toddlers. She was writing about the wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, but she could just have easily penned that paragraph for a 1906 edition of Harpers Bazar. Americans in the early 1900s were just as smitten with royalty as some are todayand just as taken by their cuteness.

In 1906, there may have been more to the royal obsession than merely cute kids. Dramatic changes had occurred in the United States. We had survived a horrific civil war, put an end to slavery, created great wealth, and saw women move from dependent wallflowers to fellow students and coworkers. The June 1906 issue of Harpers frankly discussed the growing popularity of women avoiding marriage so they could live the single lifea shocking new idea. In Australia, women had the right to vote; in the U.S., the idea of womens suffrage had been bubbling since the days of the Revolutionary War. Modern girls, as they always do, were scandalizing the establishment. Maybe, amid all this extreme change, traditionsuch as that seen among the royalswas exactly what Americans pined for. Royalty was not just old-school; it was firm history. It was long-lasting. It was comforting amid this crazy new world.

Next page