The Real Band of Brothers stems from a chance meeting with the actor Alison Steadman in 2003 at the launch of my book Forgotten Voices of the Great War, where she read the moving words of Kitty Eckersley, whose husband had died on the Western Front. I met Alison again five years later and she introduced me to her friend, Marlene Sidaway, also an actor. Marlene lived for many years with David Marshall, one of the earliest British volunteers in the International Brigades, and was also the Secretary of the International Brigade Memorial Trust. In this role, she told me, she was in close touch with the last British survivors of the Brigadeand, from that meeting, the book began to take shape.

To many people in the UK today, the Spanish Civil War remains something of a grey areaa conflict in which British troops were not engaged, and one that was eclipsed in the public perception by the Second World War. But the Spanish Civil War was a vicious and prolonged battle, the repercussions of which still reverberate through that country today. Many towns were destroyed and their populations massacred; the lives of half a million men, women and children were lost. Furthermore, while the British Government did not support the democratically elected Republican regime in Spain, individuals from the UK and other nations across Europe, incensed by the injustice of the Spanish struggle, volunteered their services to fight for democracy.

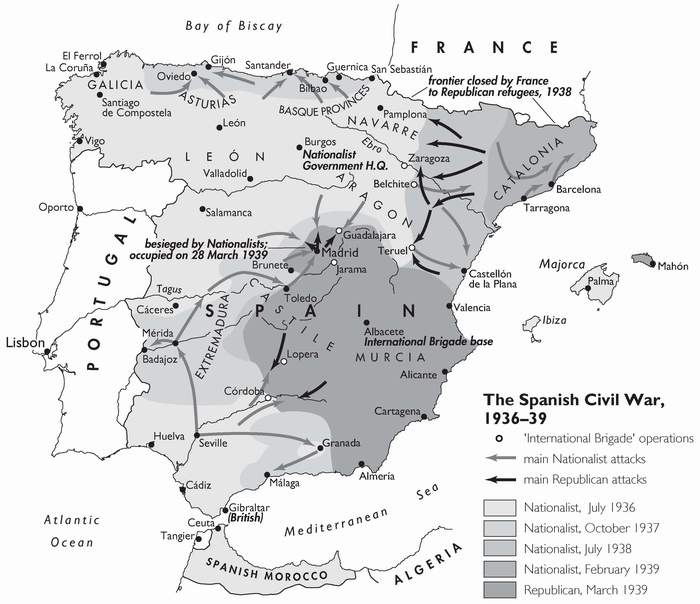

In July 1936, the army generals including General Franco led a savage military coup to depose Spains elected governmenta left-wing coalition of the Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE), the Republican left, the Communists and various regional nationalist groups. This Fascist aggression was not isolated in Spain; in the early 1930s, extreme right-wing movements were also growing under Mussolini in Italy, Hitler in Germany and, to the alarm of left-wing parties there, under Oswald Mosley in Britain.

Supported by his Blackshirts, Mosley tried to impose his authoritarian philosophies on the working-class population of Londons East End, and his political meetings often ended in violence. Eventually, in a well-orchestrated show of strength, groups of trade unionists, Communists and Jews joined forces to denounce Mosleys racist ideology and prevent his jackbooted thugs from marching through their streetsit was a stand-off that became known as the infamous Battle of Cable Street.

Some of the men and women who had seen off Mosley on that fateful day later volunteered to fight in Spain in what became known as the International Brigades. Much to the fury of these volunteers, the British Government of the day had adopted a policy of non-intervention. Not only would there be no British military support for the Spanish against Francos forces, there would be no official medical or material aid either. Although news from the Spanish war was sparse in any but the left-wing press, a growing number of people travelled to London to sign up with the Communist Party, and, in defiance of French laws against partisan military groups, made their way across the Channel, through France and over the Pyrenees to support the Spanish Republican army. Some were motivated by their political beliefs; others by their horror at the humanitarian catastrophe unfolding in Spain. The working people, already poor and living from hand to mouth, were facing starvation and disease, and many British doctors and nurses set out for Spain to offer their skills in order to alleviate the suffering their consciences could not ignore.

In the three-year conflictwhich has been dubbed the first battle of the Second World Warmany of those volunteers lost their lives. To all who freely offered their services, for whom the cause was indeed just and one they were prepared to die for, the war was a life-changing experienceand one that none would regret, despite the consequences.

As I started working on The Real Band of Brothers, just eight veterans of the International Brigades remained in Britain and, together with the award-winning documentary maker Matt Richards, I travelled across the country to interview and film these remarkable characters. The oldest, Lou Kenton, turned 100 in September 2008, and former nurse Penny Feiwels hundredth birthday is in April 2009. She is still full of vigourand still cursing Franco for inflicting the terrible injuries on innocent children that she witnessed. Archaeology student Sam Lesser fought for two years to hold the City University of Madrid. Paddy Cochrane, who at seven had seen his father shot by the Black and Tans in Dublin, believed that he himself would suffer a violent death in Spain. Bob Doyle, who, after being held prisoner by the Fascists, returned years later to stamp and swear on Francos grave. Jack Jones would later become leader of the Transport and General Workers Union, and fought fearlessly at the Ebro in the last battle of the war. Les Gibson, a founder of the Young Communist League in west London, fought through Jarama, Brunete and the Ebro, and survived life-threatening colitis to return to the action. Jack Edwards, at home a very active union member and political activist, returned from the war with his determination to fight Fascism undiminished; within months he joined the RAF to continue the battle against Hitler.

Over a number of weeks I had the great pleasure of interviewing these eight extraordinary survivors in their own homes. Matt Richards recorded their testimonies on film and tape, and has subsequently written a script based on the interviews, which was commissioned as a two-part documentary for the History ChannelThe Brits Who Fought for Spain.

All these old Brigaders had endured an extremely tough Edwardian childhood, but retained an extraordinary vitality and a clear perspective on how the war had changed their lives forever. I am in awe of their still-vibrant sense of anger and defiance. Now, as I write this preface, I have just learned with great sadness of the passing of Bob Doylehe was an indomitable spirit to the last and I was privileged to have visited him again just days before his death.

Some had told their story before, but others were opening up after a lifetime in which they had avoided talking about the war. Their testimonies are in their own words but allowance must be made for the age and frailty of their memories. Wherever possible I have checked the historical details, but sometimes the facts are buried in time. Bob Doyle and Jack Jones kindly gave me permission to use additional extracts from their respective books, Brigadista and Union Man.

It is now 70 years since the end of the Spanish Civil War, in which over 500 of the 2,500 British volunteers for the International Brigades were killed. All the survivors, however, were united in the one beliefthat they were fighting against the evil of Fascism, and that it was no less than their duty to do their bit. As more than one speculated, if other European governments had supported the Spanish Republic and quashed the Fascist threat in its infancy, the course of history might have been different, and perhaps there would even have been no Second World War.

Whatever their sense of the role of the Spanish Civil War in a historical context, all are personally bound by the values of comradeship and deep loyalty. They fought for a cause, asked for no payment, and saw many friends die. But every one agreed that they would do it all again.