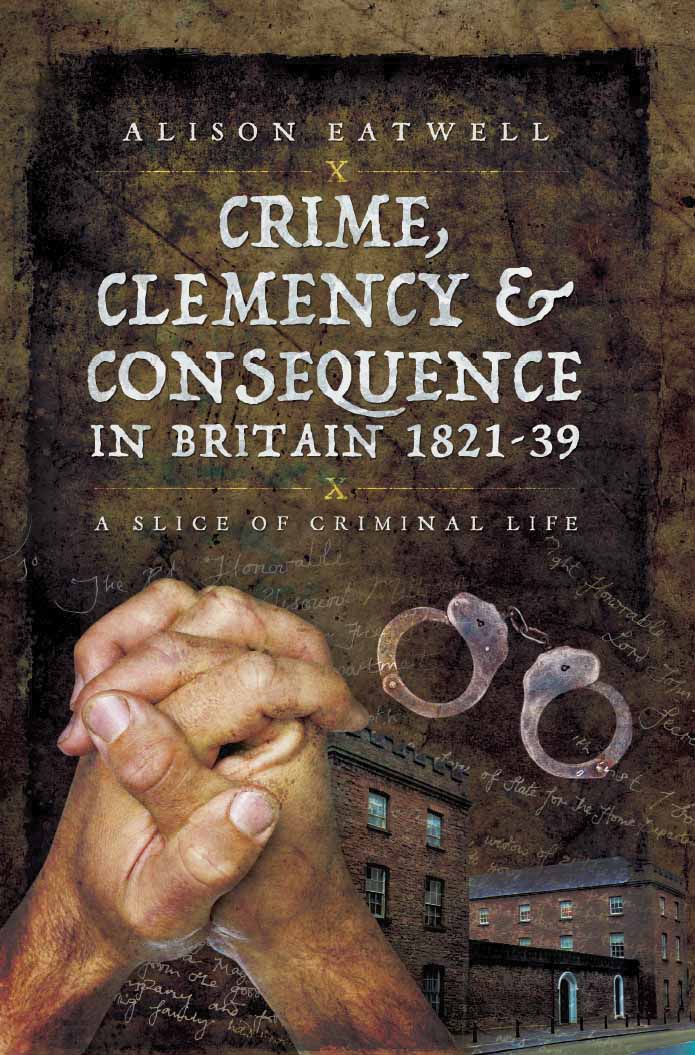

Crime, Clemency & Consequence in Britain 182139

Crime, Clemency & Consequence in Britain 182139

A Slice of Criminal Life

Alison Eatwell

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword History

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Alison Eatwell, 2017

ISBN 978 1 47383 031 8

eISBN 978 1 47383 033 2

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47383 032 5

The right of Alison Eatwell to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Books

Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History,

Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime,

Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing,

Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Acknowledgements

W ith thanks to the staff and volunteer editors and cataloguers working on the HO17 Criminal Petitions for Mercy Project at the National Archives, Kew, in particular Briony Paxman, Colin Williams, Celia Cartwright, Brenda Mortimer, Barry Purdon and Anne Wheeldon. Thanks also to Roy Metcalfe and Mac Mowat.

Old Bailey Online -The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, 1674 1913, has been used for background reading and as research for specific Old Bailey cases. Where appropriate, case reference numbers are included in the End Notes.

Textual Conventions

T hroughout the text the following conventions have been applied:

I have used the term Home Secretary in place of Principal Secretary for the Home Department to ensure standardisation amongst the petitions. Home Office is used throughout in the place of Home Department for the same reason.

Where variations in the spelling of names have been found, the different versions have been noted, but thereafter a single spelling has been used, except if the name appears within a quotation.

Unless it is clear where a case is located, or if otherwise stated within the petitions and documents sent, I have added the current city to situate an address where only street names have been given by letter-writers eg. London.

Spelling and grammar, within quotes, is that used by the sender. However, some quotations may have been modernised to make the sense accessible while retaining their original meaning.

Introduction

H istorians have often used Court and Home Office records to reconstruct the key events in a prisoners life, but these documents rarely reveal the level of incidental detail or personal circumstance which allows us to view the prisoner as an individual reacting in a dynamic world. However, The National Archives in Kew, Surrey, holds thousands of petitions from the earlier decades of the nineteenth century. These petitions, from prisoners, their families, employers, supporters or even prosecutors, were written after the prisoner had been sentenced, in the hope of gaining a commutation of their punishment.

Held in series HO17 and HO18 the petitions are a unique and exciting source of rare glimpses in to everyday routines, working conditions, illnesses, relationships, foreigners in Britain, Britons transported overseas, and life in a locality. They are sometimes accompanied by witness statements and other supporting documentation. By using these primary sources, this book hopes to bring to life some of the individuals caught in the justice system and show how they responded to the position in which they found themselves, providing a flavour of criminal activity at the time.

The individual cases in this book are taken from HO17 (and associated documentation), and this series contains around twenty thousand petitions in total. Whilst the petitions here do not claim to be statistically representative of the series and indeed it is not certain how many petitions received by the Home Office were later misfiled or otherwise not included they begin to illustrate the breadth of issues and differing criminal activity in the 1820s and 1830s, the wide range of people involved and the legal procedures at the time. They are all unified by one thing at least; they are written by people who were strongly motivated, and often desperate, to take the time and bear the cost to appeal for a reduction in their own or their loved-ones sentence. Although some prisoners claim to be innocent, all here had been found guilty and sentenced as such. These are cases in which people had much to lose and much to gain.

This book also allows us to consider how much, or how little, has changed in the types of crime committed, the circumstances and those committing them. It also demonstrates how human emotions remain constant across the centuries and shows that many of the background social and political situations have resonance today.

At the heart of the book, in all senses, are the letters and paperwork which show private feelings and personal details. Read as individual cases, each subject is fascinating; viewed together, the collection reveals a unique and often unexpected insight in to life in 1820s and 1830s Britain.

Chapter 1

Situating the Petitions: A Brief Overview of the 1820s and 1830s

A ccording to the 1821 census, England and Wales had a population of 12,000,236, Scotland 2,091,521 and Ireland 6,801,827. By the 1841 census, the figures had risen to 15,914,148 for England and Wales, 2,620,184 in Scotland and 8,196,598 in Ireland. Much of that population had been lured away from agriculture and in to the growing cities as people looked for work. In 1841, less than two thirds of Londons residents had been born in the capital, many drawn from other parts of Europe as well England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland.

After a period of economic decline, due to demands on its finances by the Napoleonic Wars, the country experienced an economic boom in the early years of the 1820s. However, sudden recession was to follow in the middle of that decade and, with the British economy largely dependent on cotton, recession would occur again in the 1830s, though the expansion of the railways would then bring increasing stability. The Bank of England was not the only source of bank notes; many independent country banks issued their own, as did banks in Scotland and Ireland. But many smaller banks were unable to withstand the challenging conditions and in the years following the financial crisis in 1825 and 1826, the Bank of England began to open branches outside the capital in a move to help stabilise the currency.

In art, the first half of the nineteenth century saw a return to themes of personal experience and emotional response, especially where nature was concerned. In 1821, John Constable painted The Hay Wain and the following year, George IV commissioned J.M.W. Turner to paint a large picture of The Battle of Trafalgar which he delivered in 1824. It was presented to the Naval Gallery in Greenwich Hospital in 1829.

Next page