Troublesome Women

Gender, Crime, and Punishment in Antebellum Pennsylvania

Erica Rhodes Hayden

The Pennsylvania State University Press

University Park, Pennsylvania

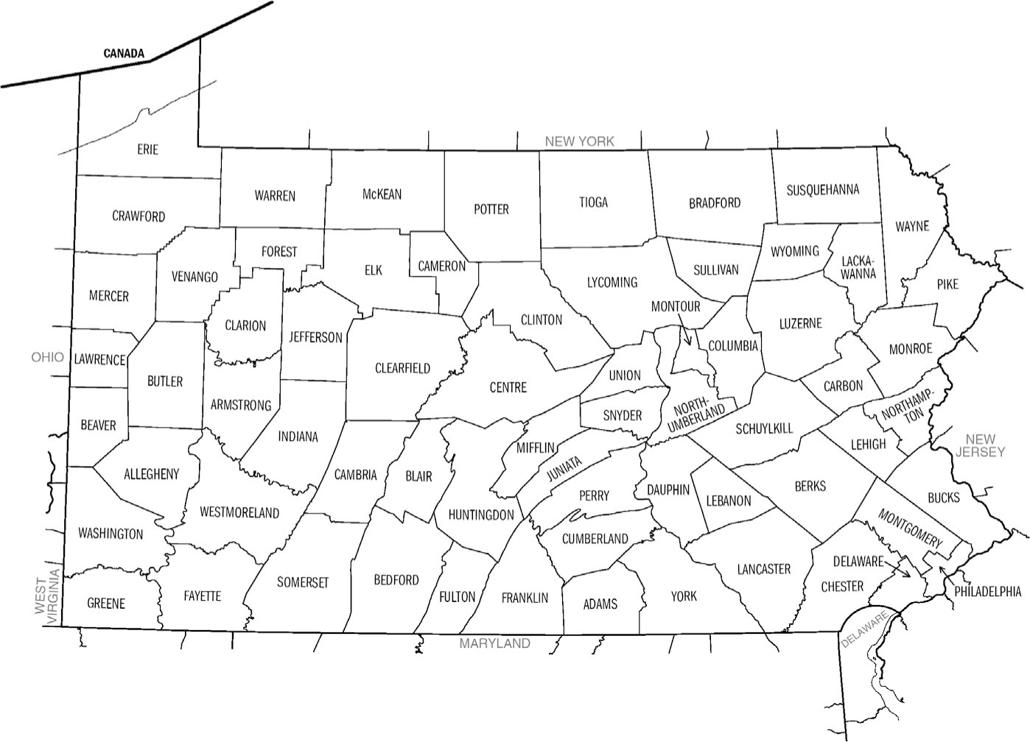

Frontispiece: County map of Pennsylvania. 2006 Derek Ramsey (Ram-Man) (from U.S. Census Bureau).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hayden, Erica Rhodes, author.

Title: Troublesome women : gender, crime, and punishment in antebellum Pennsylvania / Erica Rhodes Hayden.

Description: University Park, Pennsylvania : The Pennsylvania State University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: Examines the lived experiences of women criminals in Pennsylvania from 1820 to 1860, mainly as they navigated the nineteenth-century legal and prison systemsProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018035752 | ISBN 9780271082264 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Female offendersPennsylvaniaHistory19th century. | Women prisonersPennsylvaniaHistory19th century.

Classification: LCC HV6046.H39 2019 | DDC 364.3/740974809034dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018035752

Copyright 2019 Erica Rhodes Hayden

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Published by The Pennsylvania State University Press,

University Park, PA 168021003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ANSI Z39.481992.

For J. C. and Jamie, with love always

CONTENTS

Part 1:

The Crimes

Part 2:

In Prison

Appendixes

Researching and writing a book is not completed in a vacuum. It takes numerous people to accomplish this task. This book would not have been possible without the financial support from Vanderbilt University, which facilitated research for this manuscript. I also wish to thank the American Philosophical Society for their support as a Nancy Halverson Schless Fellow in 2010, and I particularly want to thank Earle Spamer and Roy Goodman for their interest and guidance in my project while in residence at the Society library. Furthermore, the librarians and archivists at county archives, historical societies, and courthouses across Pennsylvania have been invaluable sources of information and help.

I am grateful to all those who provided feedback on portions of this project. I especially thank professor Richard Blackett, who has offered patient, unending guidance and motivation throughout the years and has taught be how to be a good historian. He does so with a great sense of humor, sage advice, and a keen eye for writing.

Friends make projects like these bearable. The support of Caree Banton, Frances Kolb Turnbell, Nicolette Kostiw, Angela Sutton, and Nick Villanueva has been invaluable, as they provided endless laughter, helpful ideas and suggestions, and group therapy sessions over the years.

My current and former students also have inspired me along the way. They listened intently as I lectured on prisons and crime, asking probing questions that not only made class enjoyable but also challenged me as a scholar while I worked on this project. I especially thank my history students at Trevecca Nazarene University who have read portions of this work and provided many useful comments and recommendations. Kirsti Arthur, in particular, gave her time to help scroll through microfilmed prison records and painstakingly transferred her findings into spreadsheets for statistical analysis. She is a dedicated historian in the making. This book has given me the opportunity to demonstrate to my students one aspect of what it means to be a historian and engage them with the process.

Trevecca Nazarene University has been a nurturing place to continue this project. Supportive colleagues in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences and a campus-wide appreciation for faculty research at a teaching-intensive university have enabled me to pursue my research and writing. Parts of this manuscript have been presented at the Faculty Research Symposium in 2015 and 2016.

Excerpts from this work have been previously published, and it is with gratitude that I have been given permission to reprint them here. Excerpts from my chapter Letters from Inside: Prison Writings from Eastern State Penitentiary in the Nineteenth Century, part of the edited collection Incarcerated Women: A History of Struggles, Oppression, and Resistance in American Prisons, published in 2017, can be found in originally appeared in my article She keeps the place in Continual Excitement: Female Inmates Reactions to Incarceration in Antebellum Pennsylvanias Prisons in the journal Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies in 2013 and are reproduced here with the permission of the Pennsylvania Historical Association.

It has been a pleasure to work with Kathryn Yahner and the editorial and production staff at Penn State University Press. Thank you all for your guidance in this process!

The History Department at Juniata College is deserving of my gratitude as well. The dedication to their fields and students of the history faculty in particular, and the institution as a whole, is astounding. The seeds of this project were planted as I researched and wrote my senior thesis in 20067 on capital punishment in small-town Pennsylvania. As part of a summer internship at the Huntingdon County Historical Society, I stumbled across the noose from the last hanging in the county as I organized excess collection materials for the Society. That find set me on a path to research the social ramification of capital punishment in the nineteenth century and, later, the experiences of women criminals. The History Department at Juniata have kept tabs on my work as I completed graduate school, inviting me back to campus to lecture on my research and continuing to provide support and advice, for which I am appreciative.

A very special thank-you is given to my family, who have been supportive of my pursuit to become a historian. My parents and grandparents instilled the importance of the past in my life through an appreciation of family and local history, and their understanding of and dedication to higher education gave me the encouragement needed to fulfill that dream. My parents and brothers humored me with trips to historic sites and listened to me graciously as I told them about my research findings. They have been an unfaltering support system and sounding board over the years. My son, Jamie, has provided countless smiles, giggles, and chatter throughout the revision process, reminding me that there is much more to life than work. Most importantly, I wish to thank my loving husband and best friend, J. C., as he has encouraged and inspired me throughout this process. I cannot thank him enough for putting up with me during this endeavorhis patience is admirable.

In April 1839, the Philadelphia Public Ledger reported on a

Mary Woodward represents an archetype of antebellum female criminals and their experiences. Many committed petty, nonviolent offenses, with larceny being among the most common crimes. She also exemplifies the commonly shared theme of repeat offenses, resulting in longer prison sentences or moves from the county jail system to the state penitentiary. Underlying her story is the ongoing problem of the difficulty in reforming prisoners. Furthermore, the way in which the public is exposed to Marys crime and experience in court, through dramatically portrayed newspaper articles, has much power to shape how society viewed Mary and other women for their crimes. In Mary Woodwards case, the portrayals likely provided entertainment for the readers, undermining the seriousness of her seemingly difficult life. Although Marys voice is absent from the records available today, one can still piece together the experience of Mary Woodward. The crimes suggest a level of want for the items stolen, signaling that Mary lacked sufficient funds to meet her needs. We know she is black, and her race may have shaped how the reporter viewed her and chose to portray her situation, perhaps showing her less sympathy. And we know that Mary Woodward spent two years in Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia (and possibly other stints in the county prison), an institution renowned for total isolation and silencea daunting experience, indeed. What happens when she leaves the historical record is unknown, which, unfortunately, is another common theme in the experiences of female criminals and prison inmates. They fade from the record, yet their experiences illustrate the varied struggles they encountered in their time within the legal and prison systems of the antebellum era.