I NTRODUCTION

I have an old book on my shelves called How To Be Happy Though Married, published in 1886. It was written anonymously, by a graduate in the University of Matrimony, who turned out to be a minor cleric, born in Ireland and educated at Trinity College Dublin, the Revd Edward John Hardy.

It was a serious handbook for people about to get married, full of sensible advice with chapters on the choice of wife, choice of husband, honeymooning, money, servants, health and rows or, as the author puts it, if they had a few words. It was witty and clever with good anecdotes.

He tells a story about a young girl wanting to marry a young man. My dear, says her father, I intend that you should be married but you should not throw yourself away on a wild worthless boy. You must marry a man of sober and mature age. What do you think of a fine intelligent husband of fifty?

I think two of twenty-five would be better, Papa, replies his daughter.

Good joke, and one that seems very modern. I hope I can manage to be as modern and informative and amusing on the subject of being eighty.

But the aim is not just to appeal to those about to be eighty, but to everyone everywhere who feels they are getting on, that oldness is creeping upon them goodness, whatever happened to the years? which can strike you at twenty-nine and not just seventy-nine. With a bit of luck and the wind behind you, you could all make it to eighty. This is what it is like, more or less, so be prepared. Dont dread it. Embrace it.

Unlike the Revd Hardy, I intend to make my offering totally personal, as it is also a memoir. It is my report on being me, reaching the age of eighty.

The first volume of my memoirs, The Co-Ops Got Bananas, covered my long and exciting and wonderful life from my birth in 1936 to 1960, the year I got married a period of some twenty-four years. Volume two, A Life in the Day, went from 1960 to the death of my wife in 2016, covering some fifty-six years.

This present memoir should in theory therefore cover an even longer period, lets say sixty years, which will take me up to the age of 140. Cant wait to read it. And even more so to live it. Meanwhile, this book will be solely concerned with the past two years of my life, since I turned eighty.

We all do live longer these days. Being eighty is not at all out of the ordinary in fact it is commonplace. There are 1.4 million of us over-eighties in the UK cluttering up the hospital waiting rooms and the decks on cruise ships, sitting on expensive properties, with money in the bank. The Bank of Grandma and Grandpa is far better funded these days than the Bank of Mum and Dad. Some of us of course are impoverished and ill, with no home and no savings. Some of us are lonely, having ended up on our own, for a variety of reasons. We come in all shapes and conditions, we elderly folk.

My main concern is personal: to record and ruminate on what it has been like for me to be eighty what are the pleasures and pains, the joys and ignominies, and perhaps to pass on a few wisdoms, learned as well as stolen. One of the joys of being eighty is that we have been young, while the young have not been old. We know what it is like. They dont. So we are the winners. Listen up.

Reaching eighty, I found a strange thing happening to me I started boasting about being eighty. For most of the early part of my life I was rather embarrassed by looking and acting and being taken for someone much younger. Going to interview famous people for the Sunday Times in the 1960s, I was often shown to the tradesmens entrance while they waited at the front for the real and grown-up journalist to arrive. It was one reason I grew a moustache, to make myself appear older.

Until very recently, while still in my seventies, I did not generally reveal or mention my age, though I was always pleased when I was taken for younger. It would not have affected my career or social contacts, having my age known unlike a footballer or dancer or actor, who, over a certain stage, about say twenty-five, never want their age mentioned. I have spent a lifetime writing books and journalism, an occupation where no one cares how old you are, how smelly, how unfit, how haggard, how drunk, just as long as you can turn in the words on time and in some sort of readable order.

But once I reached eighty on 7 January 2016 I found myself constantly bringing it into the conversation: I was talking first dont you know how old I am? Certainly I will have another bottle of Beaujolais dont you know old I am? Scuse me, I was at the top of this bus queue dont you realise how old I am?

I will be unbearable if I ever reach ninety.

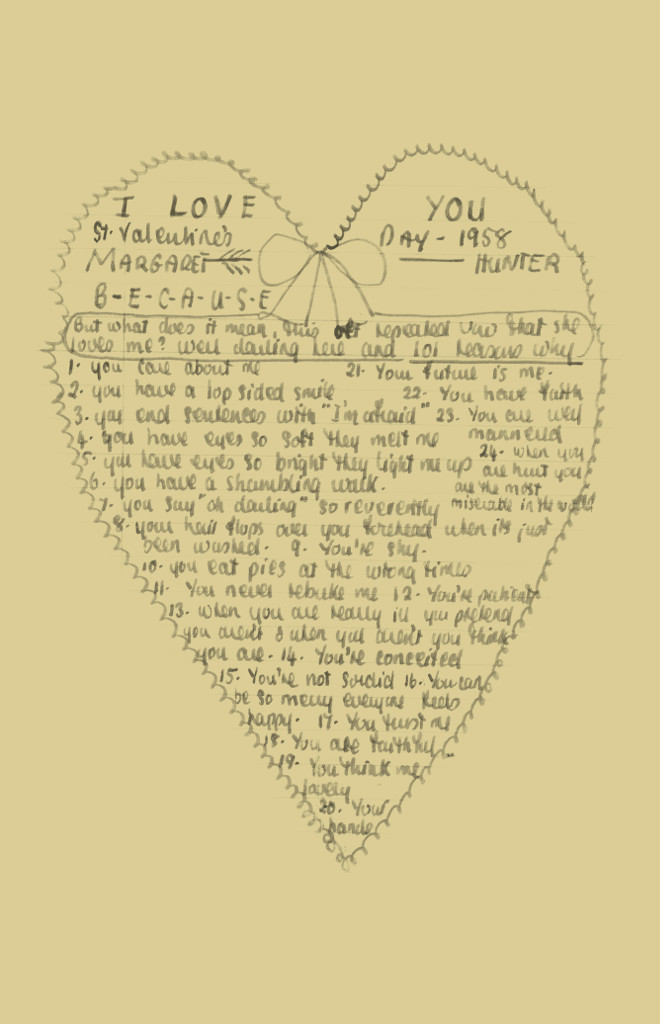

Reaching eighty coincided with my wife dying, after fifty-five years of marriage. I suddenly had to cope with being a widower, a single person, something I had never been in my adult life, living on my own, trying to manage all the domestic stuff I had never bothered to learn. I had to get to grips with being old and on my own, an elderly person, no doubt about to fall to pieces, with all the aches and pains that age brings.

So many decisions I had to make, once my wife died boring stuff like funerals, probate, wills, and then stuff that was personal and peculiar to me and Margaret. We had, for example, a country home at Loweswater in the Lake District, where for thirty years we had lived half of each year. What was I going to do with that? Could I possibly live there for any length of time on my own?

And my London home the three-storey Victorian house that we had lived in since 1963 and where our three children were born and grew up. It seemed obscene and gross to contemplate living in this large house full-time all on my own. Yet how could I bear to sell it and move somewhere smaller?

Just as unthinkable could I possibly tolerate someone else living here with me? A lodger, a stranger, entering through my front door, striding through my house?

And then chums, a companion. What was I going to do without someone to talk to, confide in, shout at, argue with, have meals with, go on holidays with, just be with, at least now and again? Obviously I was thinking that a female companion would be most pleasurable, but would I feel guilty, ashamed, embarrassed? And anyway, how would I go about it, at my great age, after fifty-five years of marriage to the same person? And what would it feel like?

My wife Margaret enjoyed being on her own. She was self-sufficient, never liked parties or social occasions, happy with her own company, along with a good book and of course visits from our children and grandchildren. She could have managed on her own. But my image of me, my character and personality, was of a jolly social animal, who loved people and parties and action, so I had always imagined I could never cope on my own. It was the thing I most dreaded. God forbid, I used to think, I hope I will never have to live on my own, just with myself, stuck all day with me. Oh no, save us from that.

So those were the problems and challenges I faced, and the decisions I had to make, serious and trivial, passing and permanent, personal and yet universal, for there are people in similar situations all over the country, all over the world, going through roughly the same things. Always have been. Always will be. This is how I personally solved them. More or less.