Table of Contents

FROM THE PAGES OF NARRATIVE OF THE LIFE OF FREDERICK DOUGLASS, AN AMERICAN SLAVE

I am going away to the Great House Farm! O, yea! O, yea! O!

(page 25)

I have sometimes thought that the mere hearing of those songs [of the slaves] would do more to impress some minds with the horrible character of slavery, than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do.... To those songs I trace my first glimmering conception of the dehumanizing character of slavery. I can never get rid of that conception. Those songs still follow me, to deepen my hatred of slavery, and quicken my sympathies for my brethren in bonds. (page 26)

From my earliest recollection, I date the entertainment of a deep conviction that slavery would not always be able to hold me within its foul embrace; and in the darkest hours of my career in slavery, this living word of faith and spirit of hope departed not from me, but remained like ministering angels to cheer me through the gloom.

(page 39)

There were horses and men, cattle and women, pigs and children, all holding the same rank in the scale of being, and were all subjected to the same narrow examination. Silvery-headed age and sprightly youth, maids and matrons, had to undergo the same indelicate inspection. At this moment, I saw more clearly than ever the brutalizing effects of slavery upon both slave and slaveholder.

(page 49)

I was broken in body, soul, and spirit. My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished, the disposition to read departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died; the dark night of slavery closed in upon me; and behold a man transformed into a brute! (page 63)

You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man. (page 64)

My long-crushed spirit rose, cowardice departed, bold defiance took its place; and I now resolved that, however long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact. I did not hesitate to let it be known of me, that the white man who expected to succeed in whipping, must also succeed in killing me. (page 69)

I assert most unhesitatingly, that the religion of the south is a mere covering for the most horrid crimes,a justifier of the most appalling barbarity,a sanctifier of the most hateful frauds,and a dark shelter under, which the darkest, foulest, grossest, and most infernal deeds of slaveholders find the strongest protection. Were I to be again reduced to the chains of slavery, next to that enslavement, I should regard being the slave of a religious master the greatest calamity that could befall me. For of all slaveholders with whom I have ever met, religious slaveholders are the worst. (page 72)

Let us render the tyrant no aid; let us not hold the light by which he can trace the footprints of our flying brother. (page 89)

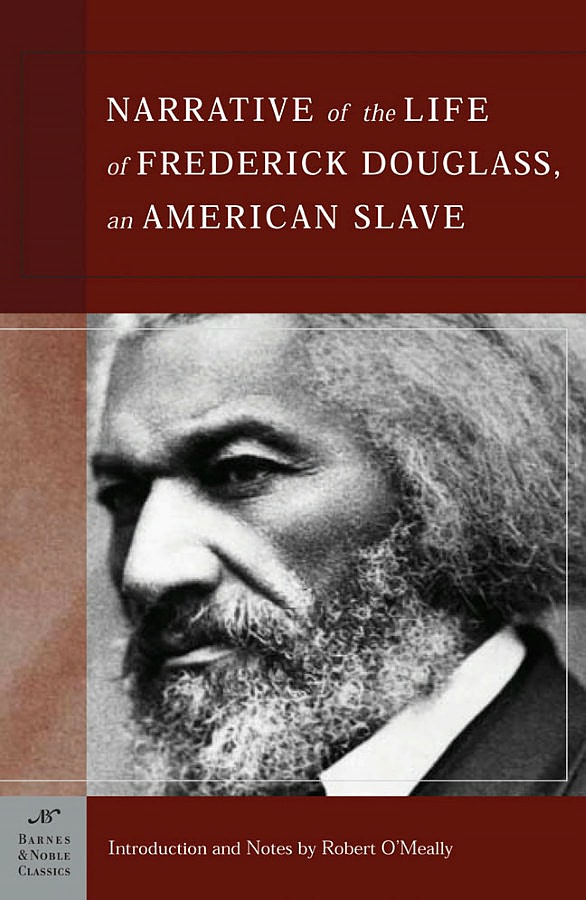

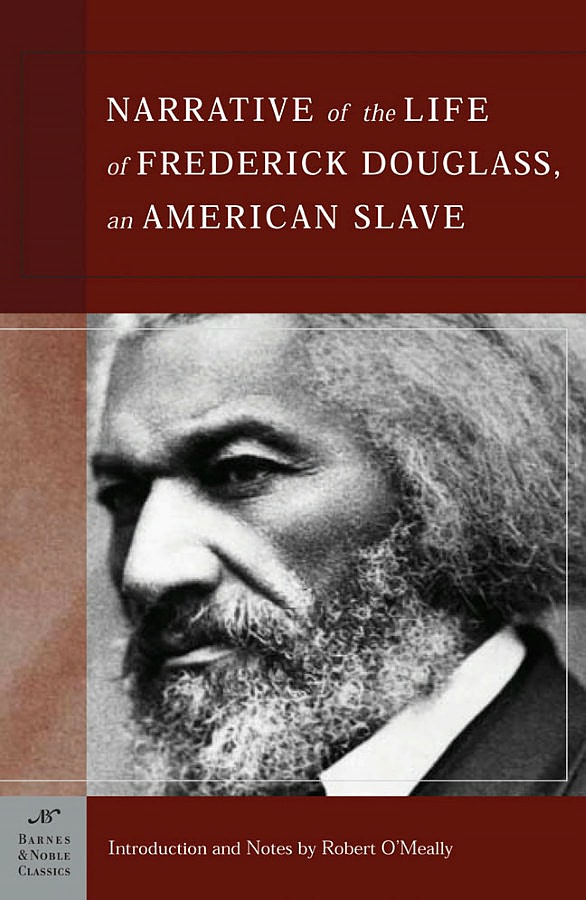

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born a slave in Tuckahoe, Maryland, in February 1818. He became a leading abolitionist and womens rights advocate and one of the most influential public speakers and writers of the nineteenth century.

Fredericks mother, Harriet Bailey, was a slave; his father was rumored to be Aaron Anthony, manager for the large Lloyd plantation in St. Michaels, Maryland, and his mothers master. Frederick lived away from the plantation with his grandparents, Isaac and Betsey Bailey, until he was six years old, when he was sent to work for Anthony.

When Frederick was eight, he was sent to Baltimore as a houseboy for Hugh Auld, a shipbuilder related to the Anthony family through marriage. Aulds wife, Sophia, began teaching Frederick to read, but Auld, who believed that a literate slave was a dangerous slave, stopped the lessons. From that point on, Frederick viewed education and knowledge as a path to freedom. He continued teaching himself to read; in 1831 he bought a copy of The Columbian Orator, an anthology of great speeches, which he studied closely.

In 1833 Frederick was sent from Aulds relatively peaceful home back to St. Michaels to work in the fields. He was soon hired out to Edward Covey, a notorious slave-breaker who beat him brutally in an effort to crush his will. However, on an August afternoon in 1834, Frederick stood up to Covey and beat him in a fight. This was a turning point, Douglass has said, in his life as a slave; the experience reawakened his desire and drive for liberty.

After a failed escape attempt, Frederick was sent back to Baltimore, where he again worked for Hugh Auld, this time as a ship caulker. In Baltimore he met and fell in love with Anna Murray, a free black woman.

In 1838 Frederick Bailey escaped from slavery by using the papers of a free seaman. He traveled north to New York City, where Anna Murray soon joined him. Later that year, Frederick and Anna married and moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts. Though settled in the North, Frederick was a fugitive, technically still Aulds property. To protect himself, he became Frederick Douglass, a name inspired by a character in Sir Walter Scotts poem Lady of the Lake.

Douglass began speaking against slavery at abolitionist meetings and soon gained a reputation as a brilliant orator. In 1841 he began working full-time as an abolitionist lecturer, touring with one of the leading activists of the day, William Lloyd Garrison.

Douglass published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, in 1845. The book became an immediate sensation and was widely read both in America and abroad. Its publication, however, jeopardized his freedom by exposing his true identity. To avoid capture as a fugitive slave, Douglass spent the next several years touring and speaking in England and Ireland. In 1846 two friends purchased his freedom. Douglass returned to America, an internationally renowned abolitionist and orator.

Douglass addressed the first Womens Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. This began his long association with the womens rights movement, including friendships with such well-known suffragists as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

During the mid-1840s Douglass began to break ideologically from William Lloyd Garrison. Whereas Garrisons abolitionist sentiments were based in moral exhortation, Douglass was coming to believe that change would occur through political means. He became increasingly involved in antislavery politics with the Liberty and Free-Soil Parties. In 1847 Douglass established and edited the politically oriented, antislavery newspaper the North Star.

During the Civil War, President Lincoln called upon Douglass to advise him on emancipation issues. In addition, Douglass worked hard to secure the right of blacks to enlist; when the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Volunteers was established as the first black regiment, he traveled throughout the North recruiting volunteers.

Douglasss governmental involvement extended far beyond Lincolns tenure. He was consulted by the next five presidents and served as secretary of the Santo Domingo Commission (1871), marshal of the District of Columbia (18771881), recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia (1881-1886), and minister to Haiti (1889-1891). A year before his death Douglass delivered an important speech, The Lessons of the Hour, a denunciation of lynchings in the United States.

Next page