Alex Haley

And the Books That Changed a Nation

Robert J. Norrell

St. Martins Press

New York

Thank you for buying this St. Martins Press ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy .

For Mary Ann Graham Norrell, in celebration of her ninety years

This book tells the story of Alex Haley, a tale whose significance is larger than one mans biography. It is the story of the remaking of American societys understanding of the black experience. Haley wrote the two most influential books on African American history in the second half of the twentieth century. Each of his books sold at least six million copies, and the films made from them were viewed and appreciated by the masses of Americans. Haley sold more books than any other African American author and all but a few white ones.

He shaped the racial sensibilities of more Americans than any other writer, black or white. Although he was not himself a black nationalist, his works, more than any other writing, gave texture and substance to black nationalism. Haley and his work deserve to be recognized as seminal influences on black identity and American thought about race.

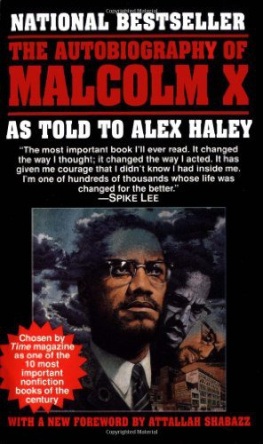

The Autobiography of Malcolm X gave millions of Americans a look into the world of blacks in twentieth-century ghettos and especially the anger that life there engendered. The book made Malcolm into an icon of black manliness and resistance to oppression. Haleys rendering of Malcolm created an archetype that challenged the image of the loving, nonviolent black male personified by Martin Luther King Jr. After Malcolms assassination in 1965, his influence on the popular imagination grew steadily, helped always by his autobiography, written by Haley.

Roots cast slavery and the black family in an entirely new light. Haley retrieved the African past of black Americans for the benefit of all people, adding new depth to our understanding of the experiences of African Americans. He created memorable characters that live today in the minds of those who read Roots or who saw the television productions based on the book. He opened the eyes of millions of whites to the hard realities of black life over the generations and spurred a national movement among Americans, regardless of race or ethnicity, to seek their family origins. Along the way, Haley taught us that our families experiences actually composed the nations history.

Despite the publishing success and the celebrity that came with it, controversy enveloped Haley soon after the publication of Roots and plagued him for the rest of his life. He was castigated personally and accused of malfeasance as a writer. The controversy hurt Haleys professional reputation and to some extent undermined his works influence on American culture. This book tries to explain how and why that happenedand also why Haley should still be remembered and his books still read.

A grant from the Social Philosophy and Policy Center at Bowling Green University in Ohio boosted this project at an early stage. Jeffrey Pauls continuing interest in my work has been gratifying. W. Fitzhugh Brundage at the University of North Carolina and Daryl Michael Scott at Howard University clarified my thinking about the issues raised in this book. Josh Durbin gave extensive help in the early stages of research, and Alicia Maskley aided at the end. Tracey Hayes Norrell and Jay Norrell each made many helpful editorial suggestions. Geri Thoma at Writers House found a home for the book. I am particularly indebted to Lisa Drew, George Berger, and Bruce Wheeler for advising me on particular issues in the research.

On a September evening in 1921, Simon and Bertha Haley drove into Berthas hometown of Henning, in western Tennessee, a village of five hundred souls lying in the lowlands not far from the Mississippi River. Bertha brought a present for her parents, Will and Cynthia Palmer. When Cynthia opened the door that night, Bertha thrust a blanketed bundle toward her mother, saying, Heres a surprise for you. It was a six-week-old baby boy. Bertha had kept her pregnancy a secret from her parents. The concealment was odd, especially because Bertha enjoyed a loving relationship with her parents, and it probably indicated ambivalence about having a baby in her early twenties.

Simon and Bertha had traveled a thousand miles from Ithaca, New York, where Simon was a graduate student at the Cornell University School of Agriculture. They were newlyweds, having met at all-black Lane College in Jackson, Tennessee, and married the previous year at the New Hope Colored Methodist Church of Henning. The nuptials had been grand by Henning standards. Will Palmer had bused in the Lane choir to perform at the wedding of his only child, a sign of the prosperity Will had enjoyed during his twenty-five years as proprietor of the W. E. Palmer Lumber Company. The clearest indication of Wills wealth was the new, twelve-room house to which Simon and Bertha brought their son.

Will and Cynthia were overjoyed with their grandbaby, called Palmer but also named Alexander for Simons father and Murray for Cynthias father, Tom Murray, who had established his family in Henning in 1874. Will Palmer had longed for a son. His and Cynthias own firstborn, a boy, had died as an infant. Will immediately began minding little Palmer. He built a crib and installed it at the lumber company in order that he might take the baby to work with him. Cynthia doted on the little boy almost as much. Early on, she took over much responsibility from Bertha for rearing Palmer.

A tall, brown-skinned woman with flowing dark hair, Bertha considered herself a musician above all. She had studied with a white teacher from Memphis, then at Lane, and at the music conservatory at Cornell during the previous year. In his new house, Will built a music room from which Bertha conducted Saturday afternoon recitals for residents of Henning, black and white. Simon, the grandson of two Irish immigrants who fathered children with slave women, was light enough to pass for white. He grew up in poverty in Savannah in western Tennessee, but he intended to move up in the world. After Lane, he graduated from North Carolina A&T in Greensboro. He enlisted in the military, serving in World War I and rising to the rank of sergeant in an all-black unit that fought at the Argonne Forest, where they were gassed. Simon enjoyed taking Henning residents into Will Palmers vegetable garden and identifying okra and cabbage by their Latin names. At the New Hope church, Simon had sung In the Garden with Berthas accompaniment, and he liked to opine after services on subjects about which he was expert, all the while twirling the Phi Beta Kappa key attached to the lapel of his three-piece suit. Dad would start talking all kind of wisdom, using big words that not a soul in the crowd understood a syllable of except him, Palmer recalled. After a while all eyes in the crowd were on that little key. Sister Scrap Scott, a feisty local woman, always stood directly in front of Simon as he pontificated. One day she pointed at the key. Fessor Haley, what is that? He explained in Greek and Latin phrases about the Phi Beta Kappa honor society. Sister Scrap was not satisfied. But Fessor Haley, what do it open?

Next page