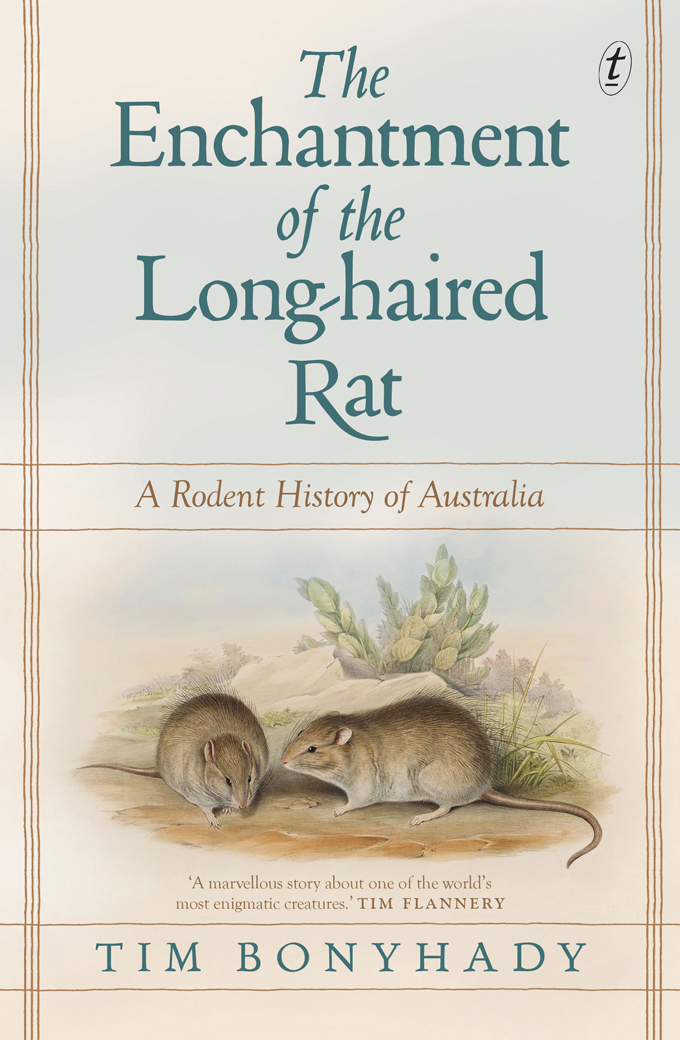

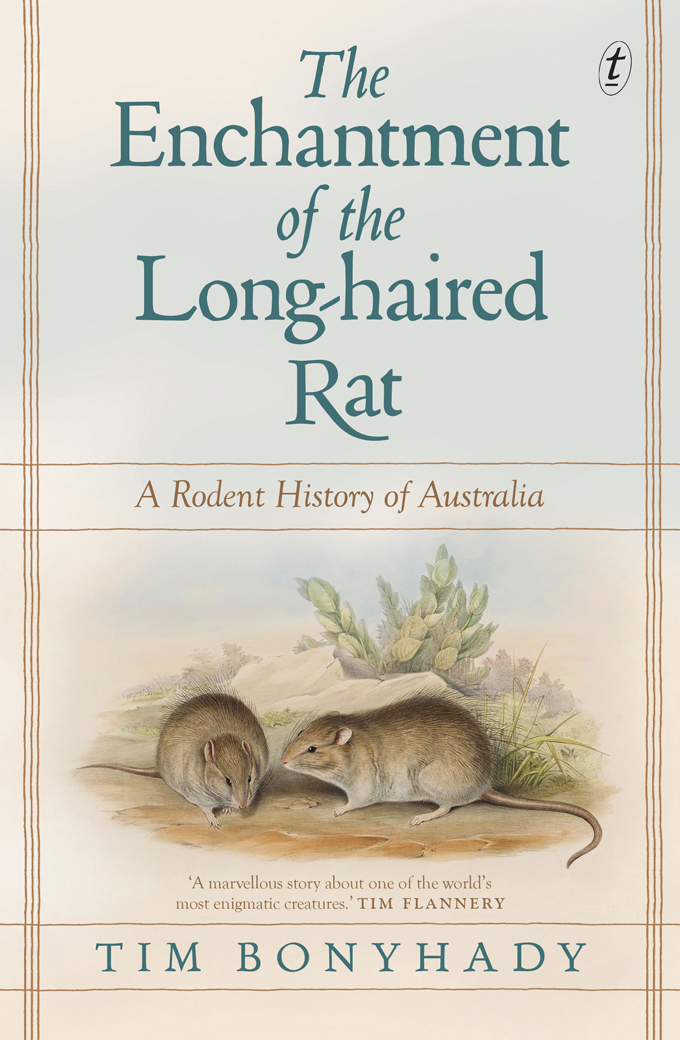

The Enchantment of the Long-haired Rat tells the story of a small Australian rodent known for its fast and prodigious spread after big rains: plagues for the European colonists who feared and loathed all rats; an abundance of food for the indigenous peoples who feasted with delight in these times of plenty.

While the rats brought despair and hardship for the early colonist eating not only crops and supplies but clothes, boots and saddlery, their presence also offered a lifeline as a food source. The Burke and Wills story might well have had a different ending had the hapless explorers been tempted to follow the example of the Aboriginal people and make use of a nutritious and readily available meal.

Tim Bonyhadys account from the earliest evidence of it, found in caves and overhangs, to its most recent boom triggered by the immense rains across Australia of 201011 and current research of its mysterious life presents a fascinating view of Australias history, illuminating a species, a continent, its climate and its people.

The Enchantment of the Long-haired Rat

For Nicole Moore of Balranald

They talked of myriads, legions, swarms and armies of visitations, invasions and plagues. Estimates of their numbers ran to not just hundreds or thousands but millions. Where passenger pigeons were once so abundant in North America that they blocked out the sun, Australias long-haired rats left no trace of whatever preceded them. By one account, they obliterated wheel and horse tracks for miles along a main road as they paddled down the sandy soil like a flock of sheep. According to another, all tracks through a pastoral station were erased each night by the passing swarms, as if the surface of the soil had been swept by a broom.

These episodes were all the more remarkable because the rats were usually few and rarely to be seen. Their plagues were even more extraordinary because, as the rats multiplied and spread, they attracted large numbers of dingoes, snakes and birds of prey which also multiplied as they fed on the rats. Then, when the plagues ended, these predators found other food, dispersed or died of starvation or disease. One was the letter-winged kite, a raptor unique to Australia, particularly dependent on the rats. The earliest European drawing of it, produced at the new settlement at Port Jackson, is the only surviving sign that in the 1790s there was a spectacular increase and then collapse in the number of rats in the far inland, forcing the kites to quit their usual terrain for the coast in search of other prey.

Aboriginal people across much of Australia have delighted in the long-haired rat as an easy source of abundant food. Some groups took it as their totem, vital to their social organisation and integral to their cosmology. The Diyari people east of Lake Eyre were probably far from alone in staging ceremonies to draw the rats towards them and increase their numbers. While Lutheran missionaries in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries sought to force the Diyari to abandon their traditions and embrace Christianity, the Diyari maintained these ceremonies to enchant the rat.

Colonists, on the whole, brought with them the deep-seated European fear and loathing of rats and ate the Australian ones only if starving, if they ate them at all. The colonists also were attacked by the long-haired rat in a way that Aborigines were not, as the Europeans supplies and possessions provided a novel lure. Far from entering their cosmology, the rat became part of settler demonology for over a century, decried as pests and vermin and much else. Yet settlers occasionally recognised the rats plagues as a most extraordinary natural occurrence and identified it as fantastic and wonderful rare, perhaps even unprecedented words for a rat, resonating with the Aboriginal desire to enchant it.

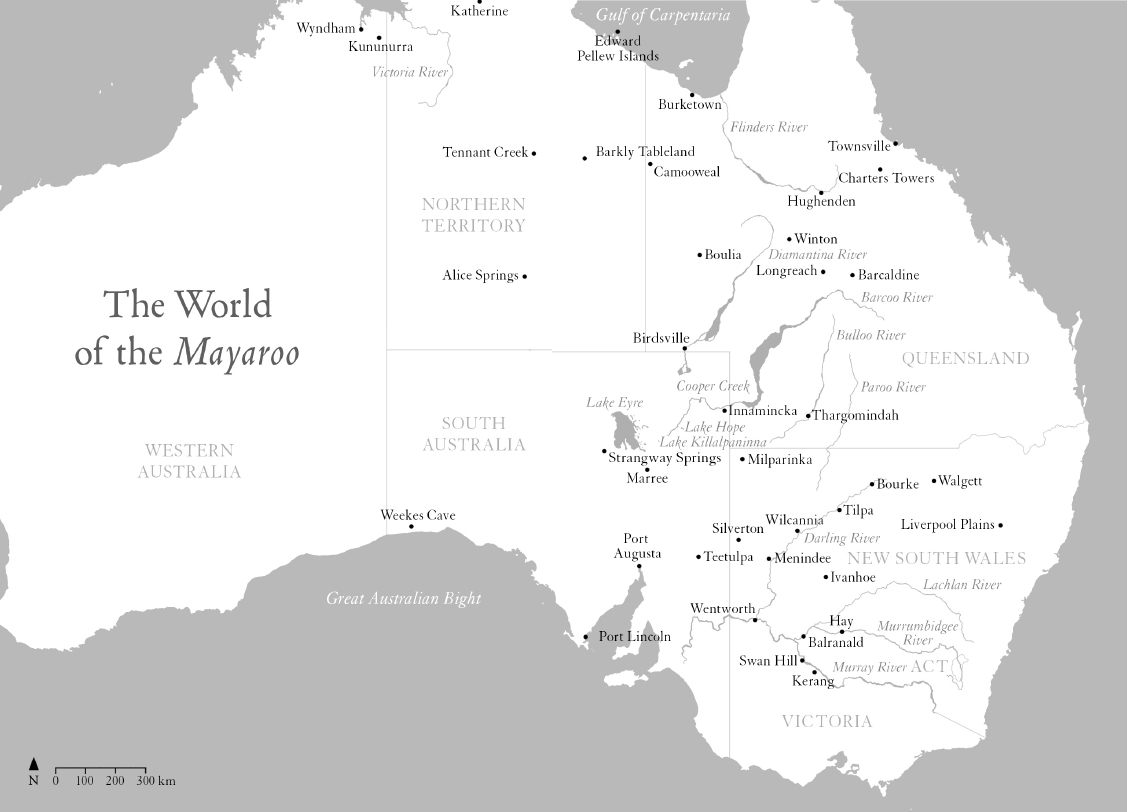

The rainfall in the Australian interior is notoriously variable perhaps more so than that of any other continents arid regions. When there are big rains and floods, prompting many plants to grow prodigiously, animals respond to this abundance of food in diverse ways. Some species increase in number only modestly. Others are more responsive. A relatively small group goes through cycles of boom and bust, multiplying in spectacular fashion when conditions are good, only to collapse when the land dries out and there is little to eat, leaving remnants surviving in areas scientists have come to call refuges. Until the late twentieth century, the long-haired rat was one of the great irruptive species of the planet, exceptional for the extent of the terrain it occupied and the duration of its plagues. One of seven Australian species of Rattus, where the Americas have none, it has been the native rat of greatest human interest and consequence since at least colonial times. Aboriginal people gave it many names including artoka, gootanga and yimala. Western science first knew it as Mus longipilis, the long-haired mouse. Now it is Rattus villosissimus or the hairy rat, commonly called the long-haired rat.

Its ancestors may have arrived from New Guinea about 1.4 million years ago, with Rattus villosissimus diverging from another species within Australia about 500,000 years ago, but physical evidence of the long-haired rat before European colonisation is limited. Its fossilised bones have been found in just one place. There are further traces of it in old pellets of barn owls, found in caves and overhangs, which often contain bones sufficiently intact to allow their identification. The first European records of the rat, from the 1840s, reveal it then reached further south and, possibly, further east than it has since. But these records are thin because colonists were yet to occupy the rats prime domains and, when they did, settlers often did not write about or depict what they witnessed. It was not until an unusually long period of huge rains and vast floods, extending from 1885 into 1888, that a big irruption became the stuff of extensive contemporaneous recording revealing how, at the plagues peak, much of the continent became an immense rattery.

This plague occurred before dams and irrigation transformed the flow of water across the country; before cattle and camels destroyed many of the long-haired rats prime habitats; and before human-induced climate change. But the colonisers had shaped what occurred. Almost a century after Europeans invaded the continent, they had put an end to almost all traditional Indigenous management of land. Their sheep had compacted the soil and eaten out native grasses. Rabbits were beginning to reach much of the terrain of the rat and compete with it for food and burrows. Cats were preying on the rats in ever more areas spreading not only because they were abandoned or strayed but also because some pastoralists bought and released as many as they could in the vain hope they might control the rabbits devastating the land. The Europeans stores of food and leather goods also attracted the rat, influencing where it congregated and how long it stayed.

The result was something fantastical, and not just because it saw the first encounter of the rat and the rabbit, with the rat heading south and the rabbit heading north, and colonists firmly on the side of the rat, hoping it might stop the rabbit. The encounter of these rodents as the rabbit and the rat were both categorised at the time occurred in a landscape which, from the settlers perspective, was largely out of control, exciting the colonial imagination. Talk of sightings of old creatures from the Dreaming of Aborigines and of new hybrid species proliferated. So did accounts of cupidity and fraud by the settlers themselves, as they competed for the spoils of the land and colonial society fractured along class lines in the face of an environmental and economic crisis.

Next page