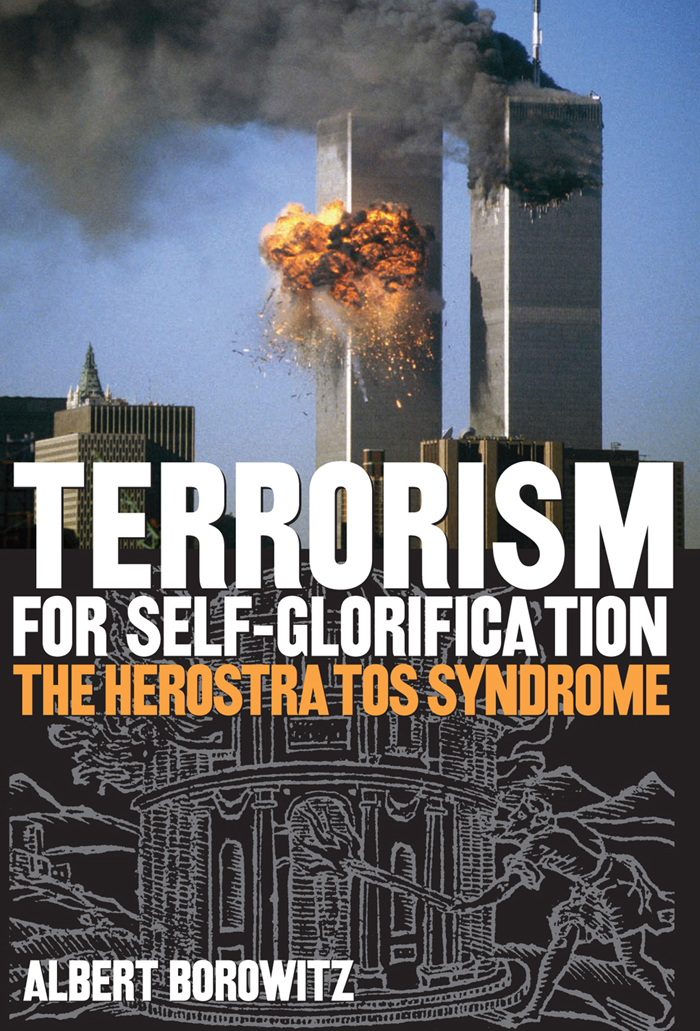

Terrorism for Self-Glorification

Terrorism for

Self-Glorification

The Herostratos Syndrome

A LBERT B OROWITZ

The Kent State University Press

Kent and London

2005 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 2004017495

ISBN 0-87338-818-6

Manufactured in the United States of America

09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Borowitz, Albert, 1930

Terrorism for self-glorification : the herostratos syndrome / Albert Borowitz.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-87338-818-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Terrorism. 2. ViolencePsychological aspects. 3. Aggressiveness.

4. Herostratus. I. Title.

HV 6431. B 692 2004

303.6'25dc22

2004017495

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

In memory of Professor John Huston Finley, who,

more than half a century ago,

first told me about the crime of Herostratos.

Contents

Acknowledgments

F IRST AND FOREMOST my thanks go to my wife, Helen, who has contributed immeasurably to Terrorism for Self-Glorification, providing fresh insights into Joseph Conrads The Secret Agent, guiding me through mountains of works on modern terrorism, and reviewing my manuscript at many stages. I am also grateful to Dr. Jeanne Somers, associate dean of the Kent State University Libraries, for her ingenuity and persistence in locating rare volumes from the four corners of the world.

Except as otherwise indicated in the endnotes, all translations from foreign languages are my own. When I bumped up against my linguistic barriers, Alex Cook and Markku Salmela came to my rescue, translating Japanese and Finnish sources, respectively. I am also indebted to the distinguished Turkish author, Nazli Eray, for procuring me an English version of her early Herostratos play. I also wish to thank the many authors who generously provided copies of their works relating to my themes. Among their number I cite notably the dramatists Carl Ceiss and Lutz Hbner, mystery writer Horst Bosetzky (-ky), and scholars Katariina Mustakallio and Kerry Sabbag.

Finally, I acknowledge with gratitude the advice of Classics professors David Lupher of the University of Puget Sound and Thomas Martin of the College of the Holy Cross on the meaning of Herostratoss name and other knotty issues.

Authors Note

I N SPELLING MY protagonists name Herostratos, I am transliterating the ancient Greek original. Variant spellings appear in other languages:

Latin | Herostratus |

English | Herostratus (or sometimes Eratostratus) |

French | rostrate |

German | Herostrat |

Italian | Erostrato |

Portuguese | Herstrato |

Spanish | Erstrato |

Spellings used in directly quoted passages have not been altered. In spelling other ancient names, I adopt the form most commonly encountered in my sources; e.g., Ephesus.

Introduction

A N IMPORTANT STRAND in the history of terrorism is Herostratic crime. This phenomenon, consisting of a violent act or series of violent acts motivated in whole or in part by a craving for notoriety or self-glorification, can be traced from the destruction in 356 BC of one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, by the arsonist Herostratos. The man identified in ancient sources as Herostratos is a shadowy figure of whose life nothing is known before he was apprehended, tortured, and executed. The death penalty was accompanied by a postmortem sentence of the type that came to be known in Latin as damnatio memoriae, the damnation of the condemned mans memory through the imposition of a ban on the mention of his name. Soon after the death of the temple destroyer this prohibition was flouted by Classical authors; through the ages and around the world the terrible name of Herostratos became paradigmatic of the morbid quest for eternal fame through crimes of violence. New attacks made against lives and monuments seemed to be motivated by personal vanity, whatever high-sounding phrases the criminal might launch in justification. Writers who tried to understand these puzzling outbreaks of murder and destruction often invoked Herostratos as an archetype.

The recognizable features of these crimes for fame, and the commentaries that these acts have inspired, make it possible to attempt a definition of what can be called the Herostratos syndrome:

- Herostratos and his followers share a desire for fame or notoriety as long lasting and widespread as can be achieved. This desire may be appeased by publicity for the criminals name but often, preferring to elude detection by retaining anonymity, he is satisfied with the celebrity that arises from his act. These alternative or combined means of gratification, publicity for the name or for the crime, reflect the same underlying Herostratic impulse, that is, a drive to maximize a sense of power. The criminal feels an enhancement of power in the form of self-glorification (the achievement of name recognition) or self-aggrandizement (the demonstration of capacity for destruction through accomplishment of a flaunting act that will live in infamy). Herostratic violence may be perpetrated by a person acting alone or in conjunction with others who may or may not share his thirst for fame.

- The aim of the crime is to cause the public to experience panic, distress, insecurity, or loss of confidence.

- A famous person, property, or institution is often chosen as victim or target. As the Roman essayist Valerius Maximus observed in his discussion of searchers after negative fame, a killer may hope, by his attack, to absorb the celebrity of his preyto be known, for example, as the man who assassinated Philip of Macedon. The same mechanism operates in arsonists and other destroyers of well-known monuments, such as the Temple of Artemis.

- A feeling of loneliness, alienation, mediocrity, and failure may trigger an envy directed against those perceived to be more successful or prestigious. Envy is exacerbated by an ambitious, competitive spirit and the conviction that avenues to success are unfairly blocked.

- The Herostratic criminal may be afflicted by self-destructive compulsions: to confess; to taunt or to more overtly aid the police who pursue him; and to commit suicide or suffer death either in the course of the crime or by execution. Since his ultimate goal is glory, the remnant of the criminals life becomes contemptible as a value in itself; it is a pawn to be traded for accomplishment of his motive.

- Herostratic violence may acquire a sacrilegious dimension when the criminal strikes a religious shrine or a secular target that has iconic significance.

- The craving for fame may combine with other motives, personal and/or ideological, in inducing a criminal act.

In November 2001, Ego-net, a German Web site commenting on the age-old phenomenon of terrorism, referred to Herostratos as the first terrorist who entered history.

In Terrorist Lives (1994), Maxwell Taylor and Ethel Quayle express their belief that a core element in any account of terrorism is that it involves the use of violence to achieve political ends. Yet their analysis of terrorist groups in Ireland, Europe, and the Middle East, based on interviews with their members, reveals significant convergences of modern terrorists motivations with those of the politically unaligned Herostratic criminal. The ideologically committed terrorists whom Taylor and Quayle have studied appear to act under the influence of a commitment even more fundamental than political allegiancebelief in the just-world phenomenon: