The Poetry of Pop

The Poetry of Pop

ADAM BRADLEY

Published with assistance from the Louis Stern Memorial Fund.

Copyright 2017 by Adam Bradley.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Designed by Mary Valencia.

Chapter titles designed by Justin Francis.

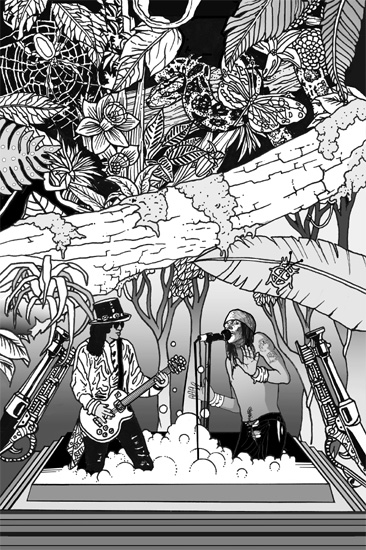

Illustrations by Leland Chapin.

Set in Century and Gotham type by Westchester Publishing Services.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956986

ISBN: 978-0-300-16502-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Ava, who loves to dance.

To Amaya, who loves to sing.

To Anna, who loves them both.

The Poetry of Pop

Introduction

Most of us live with a shifting soundtrack, songs that fill our ears as we go about our days: a workout mix, a drive-time playlist, the songs we hear in stores, the music we dance to at parties. The songs themselves are secondary; they call us to experiences rather than being experiences. We half listen, but our attention is elsewhere.

Some of us also listen in a different way. We obsess over a certain song, even over individual words and sounds in the song. We play songs in remembrance or in celebration. We listen live at concerts, or learn to play favorite songs for ourselves. Sometimes we choose these encounters; at other times they surprise us, commanding thought and feeling. Such songs comprise another soundtrack, a collection of memories accessible only through sound. These are some of mine:

Im three years old, listening to Little April Shower from the movie Bambi. I havent seen the film because my mother says its too scary. But I have the picture book and I have the LP. I clutch the album cover close to me as the music plays. The song is confusing. It makes me sad, yet I want to hear it over and over again. Im captivated by the voicesof women, then of men, in haunting harmony. I recognize only a few words: Drip drip drop little April shower. These repeat more times than I can count. The melody summons a strong and unfamiliar emotion in me. Now Id call it wistfulness. All I knew then was that this was the first song that ever made me cry and made me long for it at the same time.

Im twelve years old, playing air guitar to Guns N Roses Welcome to the Jungle. No one else is at home, so I choreograph a performance in front of the living-room speakers. First Im Slash because hes biracial like I am, then Im Axl Rose because hes a badass. I love the noise, the keening guitar, and Axls straining voice. Im drawn to the contrast between the cacophony of the chorus and the calm of the bridge, where Izzy Stradlin strums chords as Axl sings, And when youre high you never/Ever wanna come down./So. Down. So. Down. So. Downnnnn. Yeah! Axls yeah melts into Slashs bended note until they are a single sound. Theres wonder in this noise, then quiet, then noise again. Like a lot of tweens and teens in the summer of 1987, I listen to Guns N Roses because something about their music feels like me, or maybe just the me I want to be.

Im a twenty-three-year-old graduate student, about to take a three-hour oral exam on the history of Western literature before professors whose names appear on the spines of Norton anthologies. I spend the night before the exam in the bathroom, vomiting from stress. In the morning I leave my dorm room and walk to the test, my oversized headphones blasting the Wu-Tang Clans Triumph on repeat. I bomb atomically, Socrates philosophies and hypotheses/Cant define how I be droppin these mockeries/Lyrically perform armed robbery. Listening to these lines, Im conscious of their poetry: the figures and forms, the rhythm patterns and rhyme schemes that Ive been studying are here just as they are in Beowulf and T. S. Eliots The Waste Land and Elizabeth Bishops Roosters. Im mindful of how effortless the poetic patterns sound in the songs raw beats and hard rhymes. I take my headphones off as I reach the exam room door. I pass the test.

Im thirty-six years old, a first-time father, and my infant daughter wont stop crying. I sing her lullabies to no avail, then switch to pop songs. I try the Beach Boys Dont Worry Baby, Bob Marleys Redemption Song, Joni Mitchells Both Sides Now, and the entire Beatles songbook. Nothing works. Desperate, I sing Hall & Oatess Private Eyes. It does the trick. As soon as I finish the song she starts to cry again. To soothe her I sing Billy Joels Just the Way You Are, Kenny Logginss Dannys Song, and Christopher Crosss Arthurs Theme (The Best That You Can Do). She settles happily to sleep. I reluctantly face the truth: my three-month-old daughter loves soft-rock hits of the seventies and eighties. So at least once a day for nearly half a year I perform a cappella concerts for her. Im no singer, but singing these songs helps me to appreciate their careful construction, the way they work in spite of my voice. As I hold her small body against me, dancing slow circles in near-darkness, a simple fact dawns on me: Almost all songs have a spark of magic in them.

This is a book about the magic of pop songs and how a significant part of that magic resides in the language of the lyrics, both on the page and in performance. Few of us first encounter song lyrics on the page as poetry or as sheet music; instead, we experience lyrics in sound, sometimes live but usually recorded. Lyrics, no matter how artfully conceived and constructed they may be, rarely matter much alone; they exist in relation to the voice that enchants them through rhythm, melody, and harmony; in relation to the instruments that intensify their language or obscure it entirely; and in relation to the experience of pop songs when heard alone or in a crowd.

The Poetry of Pop offers the license to look unabashedly at these lyrics. It asks you to take pop songs seriously without being too serious about it. Theres something irresistible about words set in song. In fact, songs are among the most powerful forms that words take. If all art aspires to the condition of music, as Walter Pater once observed, then it does so because music achieves a register of feeling unmatched by any other mode of expression. Words in song can elicit emotions that plain speech cannot. Some songs render words percussive and melodic, nearly divested of symbol and meaning. Other songs enshrine words complex sense, building images and narratives so durable that they live on for millennia.

Situating literary matters in the dynamic space of popular songs promises new attention to old concerns. It builds a bridge between the poetic acts, both humble and sublime, taking place around us in pop music every day and those that can seem distant and forbidding when encountered in novels and plays and poems. The result is a mutually sustaining connection between disparate creations, united by a poetic practice that does not artificially discriminate between low and high culture, between the popular and the canonical. The pop music Im talking about isnt a narrow genre, but a broad descriptor that encompasses everything from Broadway musicals to country ballads, from obscure soul sides to

Next page