Contents

Yes, makin mock o uniforms that guard you while you sleep Is cheaper than them uniforms, an theyre starvation cheap.

RUDYARD KIPLING, TOMMY

Authors Note

W HEN IT CAME to writing this book, my initial approach was pure newspaper reporter: You start at the beginning, period.

Even decades ago, writing about National Hockey League games for The Globe and Mail on deadline, I couldnt manage to file whats called running copy. Basically, this is the middle of the story, and the game. The idea is that you get this done early, then write the top of the piece once you have the final score. More able colleagues can do it in their sleep, but I always had to start with the first paragraph and go to the second and so on. I couldnt write word one until the game was over.

I brought this rigid blockhead mentality to the book. The beginning, I figured, must be the introduction, because thats what comes first. In January 2007, I was just back from spending the Christmas holidays in Kandahar. Exhausted, as you always are when returning from Afghanistan, I wasted about three weeks on the stupid introduction. Id write a couple thousand words, go to bed feeling satisfied, and wake up appalled: Everything Id written was about me, and why I was writing this book I had no clue how to write.

Every morning, I destroyed what Id written the night before.

Finally, I threw myself upon the mercy of the small group of women with whom I run a few times a week. We met, as usual, in Judy Wolfes kitchen, and there, desperation in my voice, I told them my problem: I had no fucking idea how to write the fucking thing, no plan, just a lot of stories destined to move only me to tears, since I was apparently incapable of putting them to paper. I begged them to skip the run, and they agreed immediately.

As selfless as that was, I should mention it was so bitterly cold that one of our number, Karen Falconer, also known as the Weather Pussy for the obsessive way she monitors all storm fronts that come within five hundred kilometres of Toronto, had already cancelled and was missing in action.

These women are a clever bunch with diverse skills, none of which I have. Wolfe is a strategic planner by trade; Mary McIntyre is marketing director for a leading architectural practice, plus a talented jewellery designer who attends the Ontario College of Art and Design part time; Margaret McNee is a lawyer; and Janis Caruana, a legal assistant, raised with her husband, Abe, five daughters in a house that had only one full bathroom when the kids were little.

(As a measure of the state I was in, McIntyre resisted the temptation to crow about the exchange she and I had had a few months earlier. Out running one day, she asked if I had a structure for the book yet. What structure? Id snorted. Mary, Im a writer. Itll come.)

Within an hour, they had me a plan: I was to buy a big roll of paper and write down the people and elements I wanted in each chapter. I had to have a physical map of what the book would be.

I bought the supplies that same morning and followed my marching orders, starting with one of the storiesof a battle on August 3, 2006, in which four Canadians were killedId told my friends. Putting down on paper what I wanted to include in this one chapter gave me the template for the others.

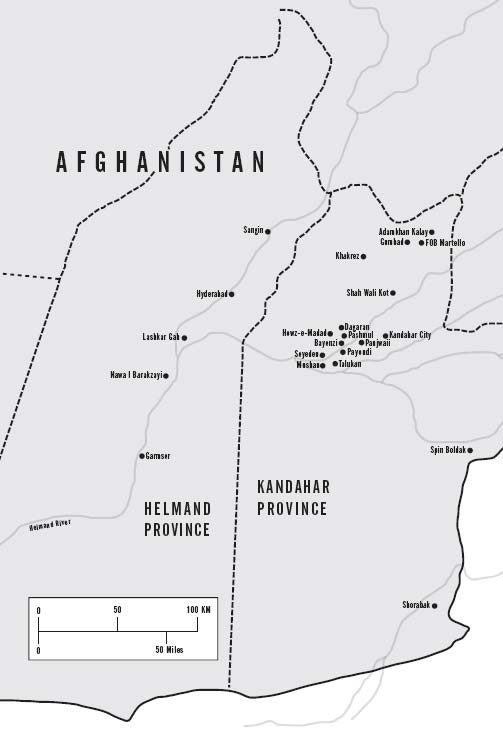

My three trips to Afghanistan were spread out over ten months of 2006; the war itself is seasonal, so there are quiet periods and busy ones. I didnt think that telling the story in a purely chronological way would work. And there wasnt a theme, really, except that I wanted to reveal the soldiers as I had found them.

While mapping out the story of August 3, I wondered whether I could tell the story through a number of significant days, days that as the boss of the book I could pick. As it turns out, I already had them all in my head: August 5, when Ray Arndt was killed; July 9, when I was caught in a battle and walked in the blood of a young reservist named Tony Boneca; April 22, when Lieutenant Bill Turner, a letter carrier Id met on one of my visits, was blown up in a massive bombing; March 4, when Tim Wilsons organs were harvested and he died; May 17, when Nichola Goddard, whom I knew only as a soothing voice on the radio, was killed.

Pretty soon, I had fifteen big sheets of brown paper taped to the walls of my little home office. I wrote down the days as they came to me, and then I wrote the chapters in the very same order. I had not only my structure, buggered up as it is, but also the title of my book.

Much later, I realized that Id mixed some of the stories that were hardest to write, where the connections were deep and personal, with some that were just a little easier. Some of the dates really are significant, certainly in terms of who was lost and sometimes because of what was learned, but all of these days matter to me because they speak to the character of the Canadian soldier.

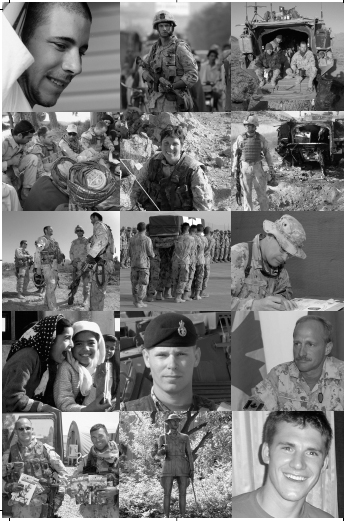

Ramp ceremony for Pte. Kevin Dallaire, Sgt. Vaughan Ingram, Cpl. Bryce Keller, and Cpl. Christopher Reid

3 August 2006

Blackest day of my life. Four perfect men lost, seven others injured. The day will be marked by acts of heroismsome witnessed, some described to me. I will have to tell the story someday, when I can do so without choking up.

FROM IAN HOPE TO CHRISTIE BLATCHFORD SATURDAY 8/5/2006 1:40 P.M.

B Y J ULY 2006, Task Force Orion was a killing machine.

Named for the conspicuous constellation of stars known as the Hunter, Orion was the Canadian battle group made up of the soldiers of the 1st Battalion, Princess Patricias Canadian Light Infantry in Edmonton; a company from the 2nd Battalion and a battery of gunners from 1st Royal Canadian Horse Artillery, both based in Shilo, Manitoba; and combat engineers.

Even into the early spring, the soldiers of Roto 1, as the seven-month tour in Kandahar Province was called, had confronted many tests that tax a soldiers resolve and ingenuity. But they had yet to face full-fledged combat.

The troops were being blown up regularly, killed and maimed by Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) planted by an enemy who went unseen and largely uncaught.

They met endless groups of village elders, and older Afghan men who appointed themselves elders, in countless shuras, or consultations. Most of these were peaceful, if occasionally galling, because the soldiers suspected, and in a few cases damn well knew, that some of the same men laying bombs by night or with certain knowledge of who was doing so would sit cross-legged with them by day, swilling glass after glass of chai tea and nodding agreeably.