IN MEMORY OF MICHAEL ALDERTON

I would like to thank the following people above all: my partner Katie Dawson, my sister Helen Canton and my mother Margaret Canton, my children Eva, Molly and Joe Canton, my uncle John Canton, Anthony Dee, Paul Gwynne, Peter Hulme, Juliet Lockhart, Sara Maitland, Ellie Mead, Jane Winch and my agent Jessica Woollard. Each has been an essential part in bringing Ancient Wonderings to life and I want to state here how extremely grateful I am to them for their various forms of support, guidance, advice and expertise.

As I set off on each individual wondering there were so many people that generously gave their guidance and help. Then there were others who offered wise words and thoughts from closer to home or helped me to secure the time and space needed to write the book. I wish to thank them all: Nick Ashton, Abdul Kareem Atteh, Ronald Blythe, Mary Cahill of the National Museum of Ireland, Mark Cocker, Bryony Coles, Ashley Cooper, Rosaline Cracknell, Jane and Desmond Crone, Phillip Crummy of Colchester Archaeological Trust, Howard Davis, Lola, Maureen and Peter Dawson, Tim Dennis, Professor David Dumville, John Fanshawe, Andrew Fitzpatrick, Susan Forsythe, Sally Foster, Godfrey and Lesley Goddard, Chris and Judy Gosling, Martin Gosling, Ros Green, Claire Halley, Doc Holliday, Jim Lock, Will Lord and his able assistant Simon, Kate MacDonald of Uist Archaeology, Rob Macfarlane, Adrian May, Chris McCully, Joe Newton, Mel Nice, Peter Nichols, Susan Oliver, Mike Parker Pearson, Emilia Psztor, Colin Peel, Harry Perkins, Craig Perry, Aldous Rees, the staff of the Rare Books and Music Reading Room at the British Library, Jordan Savage, Molly Shrimpton, Chris Standish, Phil Terry, Beth Thomas, Owen Thompson and Jessica Trethowan of English Heritage, Louise Tunnard, Owain Hughes, and Anthony Hawley of Salisbury Museum, Anna Tyacke, Sara Chambers and Michael Harris of the Royal Museum of Cornwall, Ian Warrell, and Neil Wilkin of the British Museum.

To those at William Collins who have worked so hard on the book I also offer my thanks and especially so to Myles Archibald, Tom Cabot, Julia Koppitz, Katherine Patrick and Justine Taylor.

There are certainly others whose names I did not gather but met along the way whether in cities, towns, wildernesses, fields or byways. To all those anonymous souls who have also played a part in helping me on this long journey I send my thanks too.

an illegible stone

that is where we start.

T. S. Eliot, Little Gidding

Four Quartets

I had fallen under the spell of a stone. It was in May half-term that I found a window from teaching. To find that stone I would venture to the north-east of Scotland and so I headed north until I reached the town of Insch.

Yet I had no map. When I asked where I might find one, the two women in the chemists looked to each other. They could have been twins. Both had short grey hair and glasses. Their faces were round and friendly. Had I tried the DIY store? I had. What about the post office? I had tried that, too. They smiled.

Mmm, they both said.

Then one spoke.

What about the garden centre just down the road. They might have one.

Ay, they might, echoed the other.

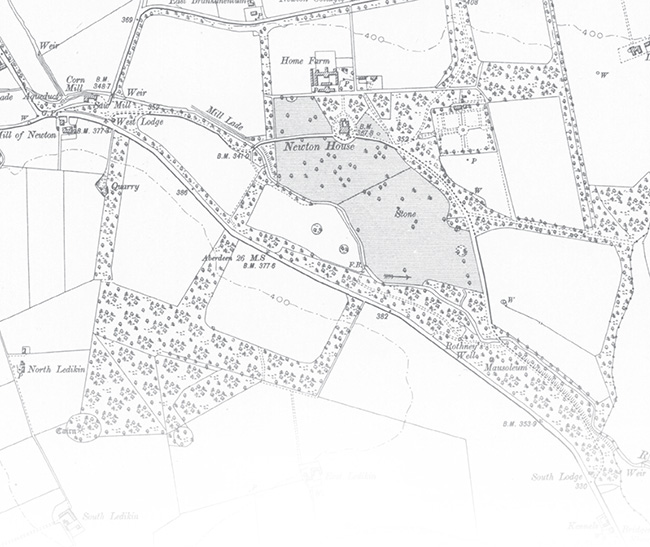

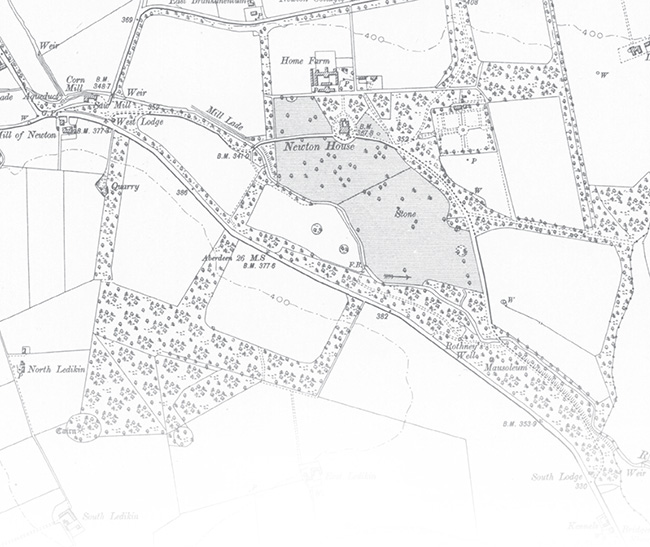

The day was grey. I walked to the edge of the town where a new housing estate was rising from the earth and then for two miles more along the B992, skipping from the tarmac of the road to the grassy bank each minute or so as a car whooshed past. A buzzard circled above. In a copse of spruce trees an incessant mewing told of young buzzard chicks. I continued to dodge the sporadic traffic and soon reached the A96 with the choice to walk north to Inverness or south, back to Aberdeen. Instead, I turned down the slip road to the Kellockbank Country Emporium. The ladies from the chemist were right. By the bars of chocolate and racks of magazines, lay just what I wanted: Ordnance Survey Explorer maps 420 and 421.

There I stood. I had travelled some five hundred miles to this windswept place in Northern Scotland, beside an A-road some twenty miles north-east of Aberdeen. I was there to see a stone a standing stone; a stone that held a story. The only problem was that there was a locked gate between me and the stone and I didnt have a key.

The tale of that stone had been lodged for years, tucked away. Every once in a while the knowledge would work its way to the surface of my thoughts. Then, I would find a way to tell the tale:

There is a stone in Scotland the story would begin.

About a year ago, I had found myself in the Rare Books reading room of the British Library in London, sometime in the afternoon of a warm day in May, and rather drifting away from the research I was meant to be undertaking on an explorer of the Arabian desert. Thoughts of that stone had arrived unexpectedly in my mind. I had ordered up some books on what I remembered was called the Newton Stone.

The facts were simple: the Newton Stone was a block of granite, or rather blue gneiss, something over six feet from top to toe on which there are carved two inscriptions. One is in Ogham script a Celtic writing system that appears as a series of scratch-like marks torn into the side of the stone. A second, more prominent, script is engraved into the face of the stone consisting of six roughly horizontal lines of writing. Each line consists of some form of exotic lettering from an ancient language: a series of swirls, curves and curlicues carved into the surface of this mass of granite. What those letters say remains a mystery. That text has yet to be deciphered.

It seemed unbelievable that there could be a piece of written script sat on British soil that no one in the world could understand. There, in that hub of all known knowledge in London, in the British Library I gazed incredulous that those simple lines of script before me held a message which all our centuries of collective study had been unable to fathom.

A week on, I sat at home in my study. The Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland website simply stated that:

The ogam-inscribed stone (The Newton Stone) is of blue gneiss, 2.03 m x 0.5 m, and bears at the top six horizontal lines of characters and an ogam-inscription down the left angle and lower front of the stone.

No indication of mystery there. A second monument that sits alongside the Newton Stone was described as a Pictish symbol stone. The stones were in the garden of Newton House, some twenty miles north-west of Aberdeen. I rang Historic Scotland.

We cant give out owner details, said the woman from the scheduling department.

She suggested I try calling the post office in the nearest village. I rang Old Rayne Post Office and elderly lady with a soft Scottish accent answered.

Im afraid were not a post office any more, she said.

She suggested I rang the Old School House. I did. Another softly spoken voice told me to try Old Rayne Community Association.

Theyll know.

I found their number and left a message on their answer machine. It wasnt going well.

Then I received an email from Sally Foster. She was an archaeologist at the University of Aberdeen who I had contacted asking for advice on the Newton Stone.

Dear James

Im afraid that I dont know how to contact the owners, other than to write to the occupiers of the house. Historic Scotlands scheduling team will have full details because the monument is scheduled.