To the women on whose shoulders we stand

Contents

Guide

S ometimes a necklace is more than just a necklace. If youre Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg of the United States Supreme Courtsomeone who has a lot to sayeven what you wear around your neck sends a message. When its the end of June and everyone is breathlessly waiting for the Supreme Court to hand down its most important decisions, those lacey or sparkly collars over her black robe, called jabots, are a clue to whats about to happen.

On June 25, 2013, Justice Ginsburg, nicknamed RBG, took her seat on the curved Supreme Court bench wearing a spiky jabot with scalloped glass beads. Its a necklace she only brings out when she has to, and that day her message was loud and clear. I dissent.

The math of the Supreme Court is pretty simple. Nine: thats how many justices there (usually) are, picked by a president to serve for life or as long as the justice wants. Four: thats how many justices have to agree to take a case, since they get asked to decide thousands of disputes and can take fewer than one hundred. Five: thats how many justices need to agree on a result. And then at least one of the majority needs to explain, in writing, why. After all, they say what the law means for the entire country, and everyone, including the president, Congress, and judges across America, is supposed to follow.

But lets say one of the justices thinks the five or more in the majority are wrong. She or he doesnt have to clam up and take it. Thats when she can publicly push back in a written dissent, to tell the world how she thinks the case should have gone. And if shes feeling particularly salty, the justice can sit in the courtroom when the majority announces its opinion and tell the world exactly how she feels. The Supreme Court is a pretty polite place, so it doesnt happen a lot.

RBG was feeling particularly salty that week.

After twenty years as a Supreme Court justice, the eighty-year-old was about to break a record by dissenting from the bench: publicly and verbally demanding her colleagues and the world listen to her protest. Thats how bad she believed matters had gotten.

That day, five justices, led by Chief Justice John Roberts, had decided the country no longer needed an important part of a law known as the Voting Rights Act. The law, first passed by Congress in 1965, acknowledged an ugly truth. State governments, which create many voting rules, had been coming up with all kinds of ways to block African Americans from voting. Thanks to the Voting Rights Act, states that had a track record of discrimination had to ask the federal government for permission to change their voting laws so the government could decide whether those laws hurt historically oppressed people.

But no more. Any racial discrimination in voting is too much, Roberts declared that morning. But our country has changed in the last fifty years. He pointed out that America had elected the first black president in 2008. Roberts said his piece, then added, evenly, Justice Ginsburg has filed a dissenting opinion.

A woman who defies stereotypes, RBG has survived sorrows and setbacks, always beating the strong odds against her. Fierce and knowing, she does not mess around, and you dont want to mess with her. But even after she had spent years as one of the most important judges in the country, some people assume they can count her out because she is small and delicate and has survived cancer twice. But on that morning, there was no mistaking her passion.

At stake, RBG told the courtroom, was what was once the subject of a dream, the equal citizenship stature of all in our polity, a voice to every voter in our democracy undiluted by race. It was an obvious reference to Martin Luther King Jr.s famous I Have a Dream speech, but the phrase equal citizenship staturemeaning everyone is treated equally under the lawhad special meaning to RBG in particular.

Forty years ago, she had stood before this very bench, as a young lawyer before nine male justices, and forced them to see that women were people too in the eyes of the Constitution. That women, along with men, deserved equality, to stand with all the rights and responsibilities that being a citizen meant. As part of a global movement for womens rights, RBG had gone from facing closed doors to winning five out of six of the womens rights cases she argued before the Supreme Court.

No onenot the firms and judges that had refused to hire her because she was a young mother, not the bosses who had paid her less for being a womanhad ever expected her to be sitting up there at the court.

At nearly ten thirty a.m. that day in June, RBG quoted Martin Luther King Jr. directly: The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice, she said. But then she added her own words: if there is a steadfast commitment to see the task through to completion. Not exactly poetry. But pure RBG. She has always been steadfast, and when the work is justice, she has every intention to see it to the end.

In her written dissent, RBG had a snappy way of explaining what made no sense about the majoritys opinion. They were killing the Voting Rights Act because it had worked too well. That, she wrote, was like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.

Although three of her colleagues agreed with her, she couldnt get one more to make a majority. But all was not lost, because the country was listening, and they were inspired.

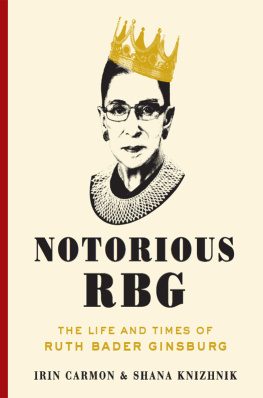

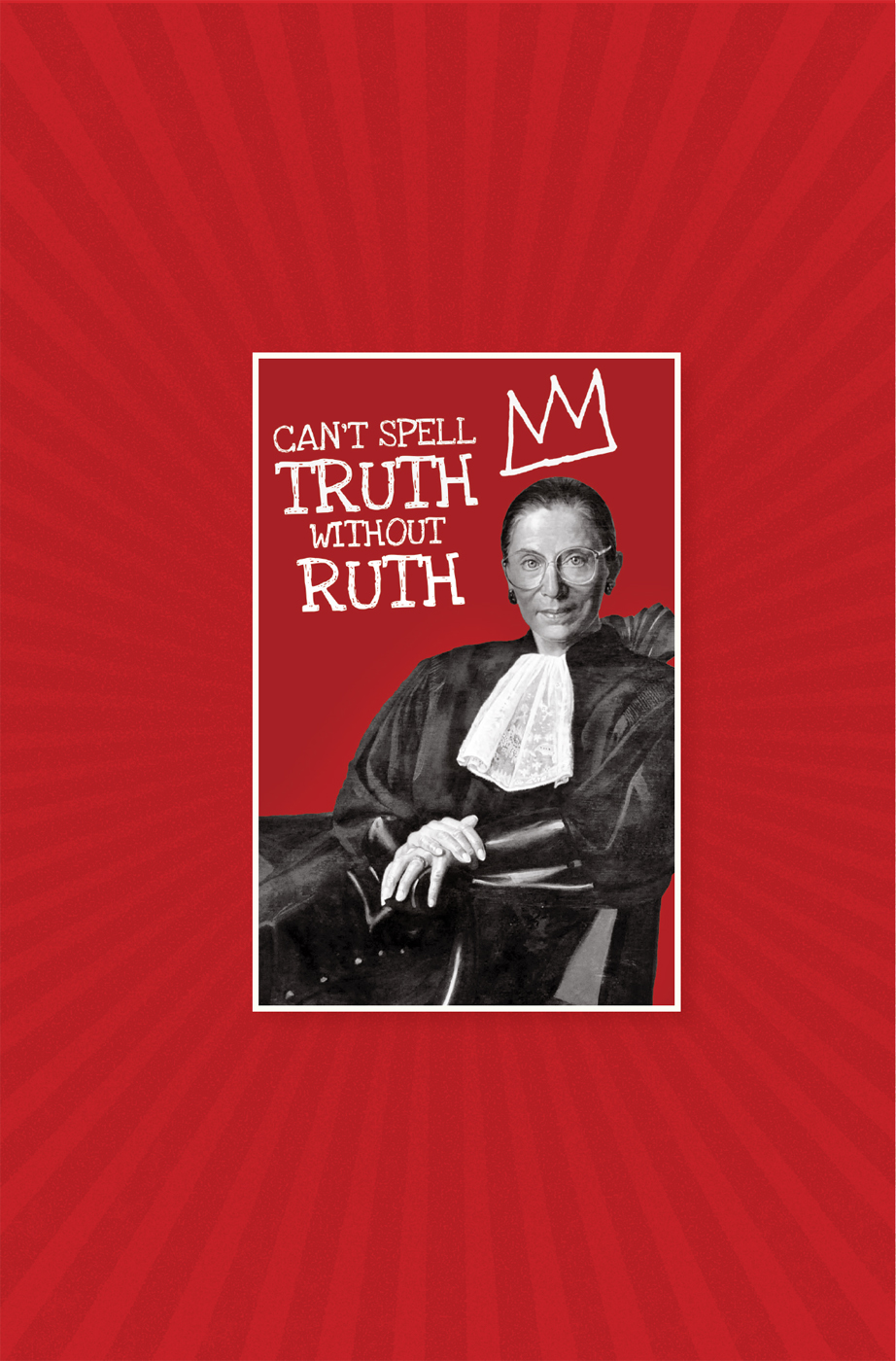

In Washington, D.C., two friends, Aminatou Sow and Frank Chi, plastered the city with stickers of RBGs image, giving the justice an illustrated crown inspired by the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat and a caption: Cant spell truth without Ruth. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, twenty-six-year-old law student Hallie Jay Pope started drawing comics of RBG, made an I Heart RBG shirt, and donated the proceeds to a voting rights organization. And in New York, twenty-four-year-old NYU law student Shana Knizhnik, one of the authors of this book, was aghast at the gutting of voting rights. She tried to look on the bright side: at least Justice Ginsburg was speaking up. On Facebook, Shanas friend gave the justice a nickname: Notorious RBG. Inspired, Shana took to Tumblr to create a tribute.

It started as kind of a joke, the reference to the three-hundred-pound deceased rapper Notorious B.I.G. After all, what did an eighty-year-old Jewish lady have in common with a nineties gangsta rapper? But there were similarities. They were both from Brooklyn. And like her namesake, B.I.G., this jurist who demanded patience as she spoke could also pack a verbal punch.