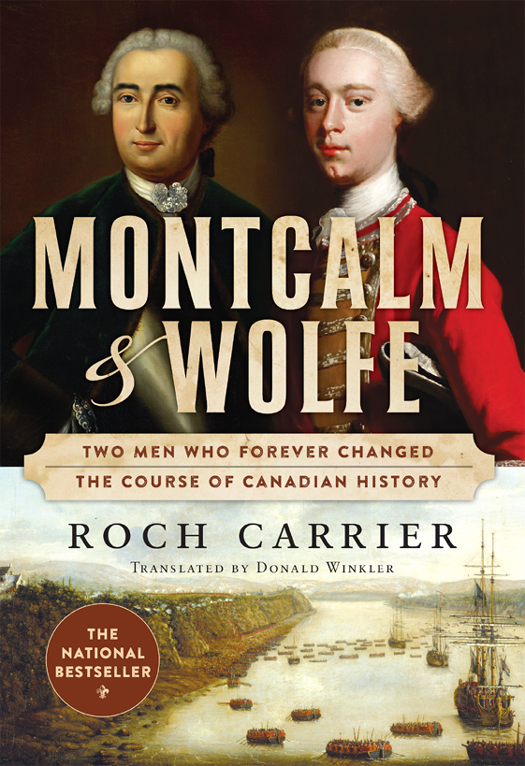

MONTCALM & WOLFE

T WO M EN W HO F OREVER C HANGED

THE C OURSE OF C ANADIAN H ISTORY

ROCH CARRIER

T RANSLATED BY D ONALD W INKLER

T wo generals serving enemy nations would die in Quebec City in a battle that took place far, very far, from their native lands. Louis-Joseph de Montcalm was French; James Wolfe was English. Wolfe was the person I most despised during my French Canadian adolescence. He had usurped the land of my ancestors, the land that was mine. It had not yet occurred to me that my French forebears had themselves appropriated a territory already inhabited by numerous peoples.

As a young poet, in France, I rode my motor scooter hundreds of kilometres on a pilgrimage to Candiac where, before his manor house, I might pay homage to Lieutenant-General Montcalm, our historys great hero, who had been unable to save my country. And I promised myself then that one day I would try to understand why.

Blessed as we are to be living in an age when intolerance and racial prejudice have been expunged from the human spirit, it is perhaps difficult for us now to acknowledge that such sentiments existed in the past. My ancestors, three or four centuries ago, their leaders, their allies, their enemies, were not proponents of politically correct thinking. In this book I have tried my best to be true to the ethos forming the backdrop to their conflicts and their stories.

A castle, a river, and so many wars

W olfe and Montcalm were both descended from families in service to their kings.

The Montcalm family, an ancient house of Rouergue (Aveyron), had been known from the end of the thirteenth century, the time of Simon de Montcalm, seigneur of Viala & Cornus. In the fifteenth century, a member of the Montcalm family was chief judge for the court in Nmes, a Montcalm was highly placed at the Holy See in Rome, and another was the matre dhtel for Charles VIII and then for Louis XII. In the sixteenth century, Franois de Montcalm was a ships captain.

Several members of the Montcalm family had shed blood for their king. Captain Louis de Montcalm, born in 1563, died in 1587 of a wound he had received at the siege of Marguerittes, a town being defended by Protestants. In 1629, after surrendering in a besieged La Rochelle, Cardinal Armand du Plessis de Richelieu sought help from another Louis de Montcalm, born in 1583, to negotiate peace terms with the Protestants. In Lombardy, while trying to stop German troops from coming to the aid of Spaniards on whom Richelieu had declared war, Marchal Franois de Montcalm died in 1632 in the region of Valtellina, in northern Italy. Eleven years later, the infantry captain Jacques de Montcalm was killed in the same place. Maurice de Montcalm, twenty-five years old, a captain in the regiment of the Grand Cond during the war with Holland, was injured by a cannonball during the siege of Naarden. When the Spanish occupied the fort of Bellegarde in 1674, in the Pyrenees on the border between France and Spain, Louis de Montcalm (the fourth of that name) was wounded during an attempt to dislodge them. He died the following year. In 1677, at the Battle of Cassel in Holland, where the troops of William of Orange faced off against those of Philippe dOrlans, brother of Louis XIV, Gaspard de Montcalm, a cavalry captain, was seriously hurt. The same day, his brother Daniel was killed at the age of thirty-two.

The Montcalms, like many Languedoc nobles, were fervent partisans of the Protestant faction in the Cvennes, but Jean-Louis de Montcalm, at the age of seventeen, renounced his Protestantism in the chapel of the Bishop of Grenoble. Appalled, his parents disinherited this wayward son. Louis-Daniel de Montcalm, born in 1676, also wanted to become a Catholic. He had met a fetching Catholic woman. As she was also a very rich heiress, their sons conversion was forgivable in his parents eyes. Louis-Daniel de Montcalm married his fiance in 1708.

A first child was born to them in 1710: a daughter, Louise-Franoise-Thrse. The future lieutenant-general who would be defeated at Quebec, Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, came into the world in Candiac, near Nmes, on February 28, 1712. Like his ancestor Jean de Montcalm, born in 1407, he would hold, among other titles, that of seigneur of the hamlet of Saint-Vran. His mother saw to it that her son was baptized as soon as possible in the Catholic Church. The next year, the Treaty of Utrecht brought relative peace to France, which had agreed to cede the land of Acadia, in New France, to the English.

Little Louis-Joseph, who now had a second sister, Louise-Charlotte, born in 1714, was delicate. His godmother, who was his maternal great-grandmother, watched over him with doting tenderness during his first years, at the castle of Roquemaure. Louis-Joseph would never forget this home with its crenellated walls built atop a black rock, nor the Rhone River, beside whose banks he took his first steps. It was near another great river, in Quebec, far from his little village, that he would take his last.

Snails and ground-up earthworms, whisked into milk with cloves

T he Woulfes, ancestors of James Wolfe, lived in southern Wales. In the sixteenth century, they immigrated to western Ireland, where they acquired lands and possessions. Having converted to Catholicism, the Woulfes were prominent citizens in Limerick. James Woulfe became one of the citys overseers. Sir Edward Seymour, an uncle of King Edward VI of England, married the daughter of Morgan Woulfe.

James I of England, opting for the Anglicans as his power base, banished the Catholics in 1604. On November 5, 1605, a band of Catholics tried to explode thirty or so barrels of gunpowder in the House of Lords, where the king was presiding over the opening of Parliament. The persecution of Catholics intensified. In Ireland, George Woulfe, then sheriff of Limerick, refused to swear allegiance to James I. He did not recognize the authority of this king newly arrived from Scotland, and as a Catholic, he could not accept that the Pope would no longer be his religious leader. James I relieved him of his responsibilities in 1613.

Politics and religion created discord among George Woulfes three sons. In 1649, Oliver Cromwell and three thousand Ironsides, fanatic cavalry troopers, descended on Ireland, putting the women and children of Drogheda to the sword with the Bible text God is love pasted around the mouth of his cannon, in the words of James Joyce. Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Woulfe was at Cromwells side. His two brothers, George and Francis Woulfe, were in the opposite camp. George, the great-grandfather of the future Major-General James Wolfe, was one of the key defenders of Limerick when the city was besieged in 1651. Francis was a Franciscan monk. Each in his own way offered resistance to the English army, but Limerick fell into the hands of its enemies. Francis was hanged. George was able to escape. The Catholic families were dispossessed. A good thirty members of the Woulfe families sought refuge on the continent, some in Paris and elsewhere in France.

Captain George Woulfe, for his part, chose Yorkshire in the north of England, a region that offered commercial opportunities. The weaving industry was growing rapidly in this agricultural county. The fugitive changed the spelling of his name, becoming a Wolfe, and he embraced Protestantism. His wife bore him two sons. Edward became an officer in the army, but when King James II of England converted to Catholicism, the king took away his commission. Shortly thereafter, William of Orange ousted James II, and Edward Wolfe became a captain in 1690. For thirteen years, he served the king throughout the Mediterranean and in the Low Countries, where he was wounded. His commission was renewed once more in 1702, by Queen Anne. Then, having retired to York, he urged his two sons to follow in his footsteps.