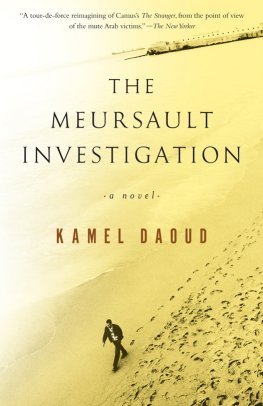

Copyright ditions Barzakh, Alger, 2013

Copyright Actes Sud, 2014

Originally published in French as Meursault, contre-enqute by ditions Barzakh in Algeria in 2013, and by Actes Sud in France in 2014.

Translation copyright Other Press, 2015

An excerpt from this novel was first published in the April 6, 2015 issue of The New Yorker.

The author has quoted and occasionally adapted certain passages from The Stranger by Albert Camus, translated by Matthew Ward (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1988). The lyrics on are from Malou Khouya by Khaled.

Production editor: Yvonne E. Crdenas.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Daoud, Kamel.

[Meursault, contre-enqute. English]

The Meursault investigation / Kamel Daoud; translated by John Cullen.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-59051-751-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-59051-752-9 (e-book)

1. Arabs Fiction. 2. Camus, Albert, 19131960. tranger Fiction. 3. Algeria Fiction. 4. Psychological fiction. 5. Political fiction. I. Cullen, John, 1942 translator. II. Title.

PQ3989.3.D365M4813 2015

843.92 dc23

2015010736

Publishers Note:

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

v3.1

For Ada.

For Ikbel.

My open eyes.

Contents

The hour of crime does not strike at the

same time for every people. This

explains the permanence of history.

E. M. CIORAN

Syllogismes de lamertume

I

Mamas still alive today.

She doesnt say anything now, but there are many tales she could tell. Unlike me: Ive rehashed this story in my head so often, I almost cant remember it anymore.

I mean, it goes back more than half a century. It happened, and everyone talked about it. People still do, but they mention only one dead man, they feel no compunction about doing that, even though there were two of them, two dead men. Yes, two. Why does the other one get left out? Well, the original guy was such a good storyteller, he managed to make people forget his crime, whereas the other one was a poor illiterate God created apparently for the sole purpose of taking a bullet and returning to dust an anonymous person who didnt even have the time to be given a name.

Ill tell you this up front: The other dead man, the murder victim, was my brother. Theres nothing left of him. Theres only me, left to speak in his place, sitting in this bar, waiting for condolences no ones ever going to offer. Laugh if you want, but this is more or less my mission: I peddle offstage silence, trying to sell my story while the theater empties out. As a matter of fact, thats the reason why Ive learned to speak this language, and to write it too: so I can speak in the place of a dead man, so I can finish his sentences for him. The murderer got famous, and his storys too well written for me to get any ideas about imitating him. He wrote in his own language. Therefore Im going to do what was done in this country after Independence: Im going to take the stones from the old houses the colonists left behind, remove them one by one, and build my own house, my own language. The murderers words and expressions are my unclaimed goods. Besides, the countrys littered with words that dont belong to anyone anymore. You see them on the faades of old stores, in yellowing books, on peoples faces, or transformed by the strange creole decolonization produces.

So its been quite some time since the murderer died, and much too long since my brother ceased to exist for everyone but me. I know, youre eager to ask the type of questions I hate, but please listen to me instead, please give me your attention, and by and by youll understand. This is no normal story. Its a story that begins at the end and goes back to the beginning. Yes, like a school of salmon swimming upstream. Im sure youre like everyone else, youve read the tale as told by the man who wrote it. He writes so well that his words are like precious stones, jewels cut with the utmost precision. A man very strict about shades of meaning, your hero was; he practically required them to be mathematical. Endless calculations, based on gems and minerals. Have you seen the way he writes? Hes writing about a gunshot, and he makes it sound like poetry! His world is clean, clear, exact, honed by morning sunlight, enhanced with fragrances and horizons. The only shadow is cast by the Arabs, blurred, incongruous objects left over from days gone by, like ghosts, with no language except the sound of a flute. I tell myself he must have been fed up with wandering around in circles in a country that wanted nothing to do with him, whether dead or alive. The murder he committed seems like the act of a disappointed lover unable to possess the land he loves. How he must have suffered, poor man! To be the child of a place that never gave you birth

I too have read his version of the facts. Like you and millions of others. And everyone got the picture, right from the start: He had a mans name; my brother had the name of an incident. He could have called him Two P.M., like that other writer who called his black man Friday. An hour of the day instead of a day of the week. Two in the afternoon, thats good. Zujj in Algerian Arabic, two, the pair, him and me, the unlikeliest twins, somehow, for those who know the story of the story. A brief Arab, technically ephemeral, who lived for two hours and has died incessantly for seventy years, long after his funeral. Its like my brother Zujj has been kept under glass. And even though he was a murder victim, hes always given some vague designation, complete with reference to the two hands of a clock, over and over again, so that he replays his own death, killed by a bullet fired by a Frenchman who just didnt know what to do with his day and with the rest of the world, which he carried on his back.

And again! Whenever I go over this story in my head, I get angry at least, I do whenever I have the strength. So the Frenchman plays the dead man and goes on and on about how he lost his mother, and then about how he lost his body in the sun, and then about how he lost a girlfriends body, and then about how he went to church and discovered that his God had deserted the human body, and then about how he sat up with his mothers corpse and his own, et cetera. Good God, how can you kill someone and then take even his own death away from him? My brother was the one who got shot, not him! It was Musa, not Meursault, see? Theres something I find stunning, and its that nobody not even after Independence nobody at all ever tried to find out what the victims name was, or where he lived, or what family he came from, or whether he had children. Nobody. Everyone was knocked out by the perfect prose, by language capable of giving air facets like diamonds, and everyone declared their empathy with the murderers solitude and offered him their most learned condolences. Who knows Musas name today? Who knows what river carried him to the sea, which he had to cross on foot, alone, without his people, without a magic staff? Who knows whether Musa had a gun, a philosophy, or a sunstroke?