S TREET

WITH

N O

N AME

S TREET

WITH

N O

N AME

A History

of the

Classic

American

Film Noir

Andrew Dickos

T HE U NIVERSITY P RESS OF K ENTUCKY

Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Copyright 2002 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2

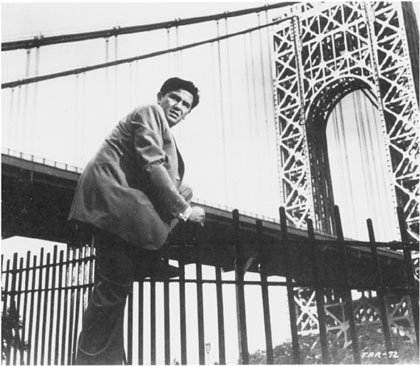

Frontispiece: Force of Evil (1948).

Joe Morse (John Garfield): a fugitive from himself.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dickos, Andrew, 1952

Street with no name : a history of the classic American film noir / Andrew Dickos.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8131-2243-0 (alk. paper)

1. Film noirUnited StatesHistory and criticism.

I. Title.

PN1995.9.F54 D53 2002

791.43655dc 212001007224

ISBN 978-0-8131-2243-4

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

To my sister, Anne who must surely remember the times we got ready for bed by preparing to watch His Girl Friday on the late show

C ONTENTS

Epilogue:

Comments on the Classic Film Noir and the Neo-Noir

Appendix:

Credits of Selected Films Noirs

P REFACE

Attempting to write a history of the film noir provokes two questions. First, what does one mean by chronicling a loose number of films considered films noirs; that is, What is the film noir? What makes a film noir? And which films best serve to illustrate film noir? Second, how can one offer a historical perspective, and of what kind, to such an amorphous cycle of films. It is hardly a neat package for historical organization, and therein lies the folly of undertaking an account of such movies that have had a significant and compelling influence on postwar cinema. Consequently, this history of a number of films considered on many counts to be noir is digressive in form, free-ranging in scope, and, through the combination of these strategies, specific and illuminating, I hope, in reaching an essential understanding of the film noir.

I discuss the subject in terms of its roots in the classical German cinema of the period following World War I, its genesis in the French cinema preceding World War II, and its flourishing in the American cinema since. The discussion touches upon film history in terms of nations and national artists, film industry developments, and sociopolitical changes. It also envelops the noir in philosophical and aesthetic concerns and their connections to film as it reflects the changing world perceived by its audiences. I also seek to discern the distinctiveness of the film noir and its motifs through the styles of its key artists in the first four decades of its existence in this country. It has been argued that, like other kinds of films, the film noir has certain narrative and structural requirements and a distinctive iconography. This is truest to the extent that these merge with the filmmakers personal vision of the noirs bleak world.

In this historical framework, the film noir is viewed for the potent force it has become in the evolution of cinematic style. But what, then, is it? Is it a style? The expression through which a mood or temperament is revealed? And what of generic conventions? What makes the noir such argumentative fodder for those wishing to define or distress it as a genre proper? Here some basic definitions and descriptions are necessary in order to discuss the film noir in a comprehensible historical context.

The film noir as I have approached it is a group or collection of films that were first made in about 1940 (1938 in France) and continue to be produced in the present. (The hesitation in calling these films a cycle lies in the implication of ending, of finality, of the cycles having been exhausted.) The year 1940 serves as an index for a climate of change in the tone of many melodrama films in America because of the sociocultural changes in American and European society, the ominous politico-historical wind of the time, and the formal developments in film present at the advent of World War II. Although the innovations of Orson Welless Citizen Kane were not yet marveled over, the gradual if not particularly anticipated change in the perception of what narrative Hollywood cinema could offer in its depiction of human problems, their ambiguities, and the social landscape from which they emanated nonetheless provided trail markers of what was to follow. The Carn-Prvert Quai des brumes (1938) and Le Jour se lve (1939) and Carns Htel du Nord (1939), for example, were potent enough indications on the international film scene to parallel, for another example, Raoul Walshs 1941 High Sierra. That film was scripted by John Huston and starred Humphrey Bogart in a decidedly more complex variation of the gangster film, where the ambiguous tone lies in contradistinction to Walshs own Roaring Twenties, made two years earlier.

The year 1940, fraught with anxiety despite an isolationist policy, was a ferment of artistic change in Hollywood that would see a fine rupture develop into a chasm between what industry entertainment had offered before and what it would soon offer in the future. Those who joined the migr movement, which was nurtured on the disillusionment of a crumbling European society, left the tyranny replacing an Old World they knew but never created and came to Hollywood. As products, too, of the artistic developments of the interwar years (modernism, in its broadest appeal), particularly the expressionist movement in Germany, German and Viennese filmmakers such as Fritz Lang, Robert Siodmak, Otto Preminger, Billy Wilder, Edgar G. Ulmer, and William Dieterle brought to a new environment lifetimes of cultural experience. To the coast of southern California they carried a philosophical worldview, ironic and bleak with the possibility both of a redemptive universe and of a place where people succumb to their weaknesses and passions; they contributed to the American screen in the guise of popular entertainment a necessary maturity, the next phase of its growth.

When Welles made Citizen Kane and John Huston made The Maltese Falcon in 1941, the American cinema could no longer ignore the schism that had been created. Screen melodrama would now, however unconsciously and unperturbingly, evoke elements of unexpectedness and intrigue that it had not aroused in the past. Characters were insinuatingly more complex, mirroring a society not always just despite the storys happy ending. What Charles Foster Kane and private eye Sam Spade have in common above all is that they are not happy men and that knowledge of the world ensures not harmony but elusiveness and uncertainty. Kane dies without the satisfaction of a precise meaning for his life, and Spade turns over a duplicitous Brigid OShaughnessy to the cops despite his feeling for her because it enforces his code of honor. But he does not forget that there are other Miss OShaughnessys out there. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, the American screen was riddled with this dark alter-side of American life. Random movie titles evoke countless variations of a despairing and haunted universe, often of fatalistic design:

Next page