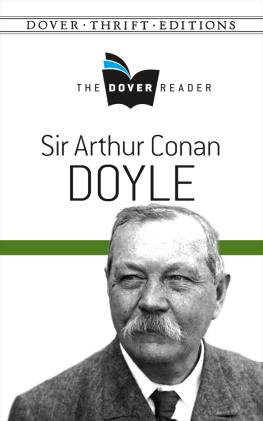

In the reams of published writing on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, he is referred to variously by the surnames Doyle and Conan Doyle. In keeping with his biographer Russell Miller, who writes that his subject was given the compound surname of Conan Doyle, I have accorded him both names here. (Conan Doyles son Adrian does likewise in his slender 1946 memoir of his father, The True Conan Doyle.)

In the interest of linguistic economy, I have generally chosen in this book to forgo honorific titlesDr., Mr., Mrs., and so on. There is one regular exception: Marion Gilchrist, the eighty-two-year-old Glasgow woman whose murder lies at the heart of the story. In previous accounts of the case, including Conan Doyles, she is always Miss Gilchrist, and I have decided, in deference to her time, place, and august age, that Miss Gilchrist she shall remain.

The currency conversions appearing in footnotes throughout this book, which translate early twentieth-century pound sterling values into contemporary pound sterling and contemporary U.S. dollars, reflect the historical inflation rate and the contemporary exchange rate of early 2018, when the book went to press.

A cast of characters appears on .

INTRODUCTION

It was one of the most notorious murders of its age. Galvanizing early twentieth-century Britain and before long the world, it involved a patrician victim, stolen diamonds, a transatlantic manhunt, and a cunning maidservant who knew far more than she could ever be persuaded to tell. It was, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote in 1912, as brutal and callous a crime as has ever been recorded in those black annals in which the criminologist finds the materials for his study.

But for all its dark drama, and for all the thousands of words Conan Doyle would write about it, the narrative of this murder was no work of fiction. It concerned an actual case: a killing for which an innocent man was pursued, tried, convicted, and nearly hanged. This miscarriage of justice would, in Conan Doyles words, remain immortal in the classics of crime as the supreme example of official incompetence and obstinacy. It would also consume himas private investigator, public crusader, and ardent nonfiction chroniclerfor the last two decades of his life.

The case, which has been called the Scottish Dreyfus affair, centered on the murder of a wealthy woman in Glasgow just before Christmas 1908. The next spring, Oscar Slater, a German Jewish gambler recently arrived in the city, was tried and condemned for the crime. His very name became so notorious that for years afterward the phrase See you Oscar was Glasgow rhyming slang for See you lateras in See you later, Oscar Slater.

But as investigations by Slaters handful of champions would uncover, the Slater case was rife with judicial and prosecutorial misconduct, witness tampering, the suppression of exculpatory evidence, and the subornation of perjury. It was, Conan Doyle declared, a disgraceful frame-up, in which stupidity and dishonesty played an equal part. A good cop sacrificed his career after he voiced deep misgivings about the conduct of the investigation and trial.

In May 1909, after a jury deliberated for barely an hour, Oscar Slater was found guilty and sentenced to death. But amid public unease at the verdict, his sentence was commuted to life at hard labor just forty-eight hours before he was scheduled to mount the scaffold. For the next eighteen and a half years he remained imprisoned, largely forgotten, on a barren, windswept outcropping in the north of the country, in a place that would one day be known as Scotlands gulag: His Majestys Prison Peterhead.

Day after day, in bone-rattling cold and blistering heat, Slater hewed immense blocks of granite; endured a Dickensian diet of bread, broth, and gruel; and often languished in solitary confinement. Had he passed the twenty-year mark behind bars, he said, he would have taken his own life.

Then, in 1927, Slater was abruptly released; his conviction was quashed the next year. What set these events in motion was a secret message he had smuggled out of prison in 1925. That messagean impassioned plea for helpwas directed at Conan Doyle.

Writer, physician, worldwide luminary, champion of the downtrodden, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had believed in Slaters innocence almost from the start. Joining the case publicly in 1912, he turned his formidable powers to the effort to free him, dissecting the conduct of police and prosecution with Holmesian acumen. But despite his influence and energy, Conan Doyle wrote, I was up against a ring of political lawyers who could not give away the police without also giving away themselves. And so a conviction that, as one commentator remarked, rested on evidence so flimsy that in comparable straits a cat would scarcely be whipped for stealing cream endured for nearly two decades as one of the most tragically attenuated judicial farces of its time.

That the story did not end with Slaters death in prison owes chiefly to Conan Doyle. As investigator, author, publisher, and backroom broker in the loftiest corridors of British power, he is credited with having done more than anyone else to win Slaters freedom in a case that many observers deemed hopeless. The Slater affair, one of Conan Doyles biographers has written, was to give Conan Doyle the chance to play a similar part in England to Zolas intervention in the Dreyfus affair in France.