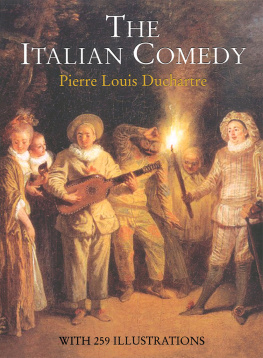

TROUPE OF THE COMMEDIA DELL' ARTE

Eighteenth-century engraving. Artist unknown

THE

ITALIAN COMEDY

The Improvisation Scenarios Lives Attributes Portraits

and Masks of the Illustrious Characters

of the Commedia dell' Arte

By

PIERRE LOUIS DUCHARTRE

Authorized Translation from the French by

RANDOLPH T. WEAVER

With a New Pictorial Supplement reproduced from

the Recueil Fossard and Compositions de rhtorique

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

NEW YORK

Copyright 1966 by Dover Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved under Pan American and International Copyright Conventions.

This Dover edition, first published in 1966, is an unabridged and unaltered republication of the work originally published by George G. Harrap & Co., Ltd., in 1929. The Frontispiece and illustrations facing page 24 appeared in color in the original edition.

This edition is published by special arrangement with George G. Harrap & Co., Ltd.

This edition also contains a new Pictorial Supplement compiled from the Recueil Fossard, published by Duchartre and Van Buggenhoudt in 1928.

International Standard Book Number: 0-486-21679-9

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 66-23390

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501

Translator's Note

DUCHARTRE'S admirable study of the Italian comedy is already well known in the original to those interested in the subject, particularly in Europe, and surely it deserves the wider attention and appreciation which a version in English can provide. The present volume offers several advantages over the two French editions of La Comdie italienne, in that the author has made extensive corrections and added fresh material to the text. He has been good enough to add also twenty-six entirely new illustrations, most of which have never before been published. It is worth mentioning in passing that nine of these, and two figures which appeared in the second French edition, are taken from a rare collection of sixteenth-century engravings called the Recueil Fossard, which M. Duchartre has recently brought out in reproduction with the imprint of his own publishing house, Duchartre et Van Buggenhoudt, of Paris. The Recueil is the result of the unhoped-for discovery by M. Agne Beijer of a magnificent in-folio album which was in the uncatalogued reserves of the Museum of Stockholm. It was made by a certain M. Fossard for Louis XIV, and, so far as is known, it had never been published, nor had more than two of the engravings ever been found in any other work.

DUCHARTRE'S admirable study of the Italian comedy is already well known in the original to those interested in the subject, particularly in Europe, and surely it deserves the wider attention and appreciation which a version in English can provide. The present volume offers several advantages over the two French editions of La Comdie italienne, in that the author has made extensive corrections and added fresh material to the text. He has been good enough to add also twenty-six entirely new illustrations, most of which have never before been published. It is worth mentioning in passing that nine of these, and two figures which appeared in the second French edition, are taken from a rare collection of sixteenth-century engravings called the Recueil Fossard, which M. Duchartre has recently brought out in reproduction with the imprint of his own publishing house, Duchartre et Van Buggenhoudt, of Paris. The Recueil is the result of the unhoped-for discovery by M. Agne Beijer of a magnificent in-folio album which was in the uncatalogued reserves of the Museum of Stockholm. It was made by a certain M. Fossard for Louis XIV, and, so far as is known, it had never been published, nor had more than two of the engravings ever been found in any other work.

Among the illustrations are three drawings by Domenico Tiepolo which Messrs Victor Rosenthal and Raymond Bloch have courteously given us permission to reproduce. The drawing from M. Bloch's collection is here published for the first time.

With the permission of M. Duchartre the translator has added a number of footnotes, usually embodying the views of other writers, explanatory of certain aspects of the subject. In order not to encumber the pages the longer of these have been relegated to appendices. In this connexion grateful acknowledgment is made to the proprietors of The Mask for the use of extracts from that periodical, and to Mr Cyril W. Beaumont for the use of passages from his History of Harlequin.

No attempt, it should be added, has been made to reconcile the differing spellings of certain names of characters, etc., which exist.

The translator wishes to express his sincere thanks to Messrs George Vardy and Pierre Loving for much valuable assistance with the translation.

R. T. W.

PARIS

June 1929

Contents

I.

II.

III.

IV.

V.

VI.

VII.

VIII.

IX.

X.

XI.

XII.

XIII.

XV.

XVI.

XVII.

XVIII.

XIX.

XX.

XXI.

XXII.

XXIII.

Illustrations

THE ITALIAN COMEDY

I

The Commedia dell' Arte

ARLEQUIN and Columbine, Isabelle and Scaramouche, Pulcinella and Pantaloon, belong definitely to romance. Behind their names are heard the guitars of the Ftes Galantes, the lingering echoes of shouts, applause, and robust laughter. Yet, as in a Watteau picture, the charm and gaiety of far-gone days die away on a minor key, for those who bore these names are long since dead, and with them all their joyous fantasy.

ARLEQUIN and Columbine, Isabelle and Scaramouche, Pulcinella and Pantaloon, belong definitely to romance. Behind their names are heard the guitars of the Ftes Galantes, the lingering echoes of shouts, applause, and robust laughter. Yet, as in a Watteau picture, the charm and gaiety of far-gone days die away on a minor key, for those who bore these names are long since dead, and with them all their joyous fantasy.

We are reminded of that bright, care-free company when, exploring some old bookshop, we come by chance upon a volume of Gherardi's Le Thtre italien, or a stray print of Beltrame da Milano, of Harlequin, or of Riccoboni. The very contact with these relics gives us pause, and all at once the festive scenes of yester-year are evoked, the shadowy figures come alive, and we sense with a vague sharpness the distant glamour of pageantry and colour still vivid in the musty pages. But the illusion is too quickly lost, and we grow aware that these beauties of the past are asleep and beyond our reach, awaiting a new Molire or else some Charlie Chaplin of the Latin race to reawaken them.

Harlequin, Punch, Columbine, and Pantaloon were, in their day, used again and again in many forms and guises, and often so badly that in the end the Italian comedy scarcely served for more than gross farces, which were sometimes amusing because they were so inept, but more often were simply tedious and vulgar. The consequence is that comparatively little is known now about the true Italian comedy, the commedia dell' arte of the Renaissance and the seventeenth century, that world of fantasy peopled with quaint characters, conventionalized but full of life, rare personalities given to antics as picturesque as the costumes they wore.

George Sand wrote:

The commedia dell' arte is not only a study of the grotesque and facetious,... but also a portrayal of real characters traced from remote antiquity down to the present day, in an uninterrupted tradition of fantastic humour which is in essence quite serious and, one might almost say, even sad, like every satire which lays bare the spiritual poverty of mankind.

Pantaloon and Brighella are eternal verities dealt with by poets rather than by psychologists or pedants. Their origin is ancient, and they will live for ever. The ancestor of Pantaloon, and his son Harpagon, is Pappus, the lecherous old miser of the Atellan. Their descendants are still with us, for Lelio is the charming gigolo of modern days, Isabelle his lovely feminine counterpart. Harlequin has lost his nonsense, and has exchanged his motley for the frock-coat of an ambitious Government official. The crafty Brighella has left his native Bergamo and Pantaloon has deserted Venice, and we have only to look twice to see them in the passing crowd.

I must insist that this illustrious family is far from being extinct. In the matter of antiquity few members of the aristocracy can boast a longer line than Harlequin and Punch. The cradle of the family was the ancient city of Atella, in the Roman Campagna, and the gallery of ancestors shows, among others, Bucco and the sensual Maccus, whose lean figure and cowardly nature reappear in Pulcinella. Next there is the ogre Manducus, the Miles Gloriosus in the plays of Plautus, who is later metamorphosed into the swaggering Capitan, or Captain. And there is also Lamia the Ghoul, who is the worthy patron saint of all go-betweens and scheming mothers.

DUCHARTRE'S admirable study of the Italian comedy is already well known in the original to those interested in the subject, particularly in Europe, and surely it deserves the wider attention and appreciation which a version in English can provide. The present volume offers several advantages over the two French editions of La Comdie italienne, in that the author has made extensive corrections and added fresh material to the text. He has been good enough to add also twenty-six entirely new illustrations, most of which have never before been published. It is worth mentioning in passing that nine of these, and two figures which appeared in the second French edition, are taken from a rare collection of sixteenth-century engravings called the Recueil Fossard, which M. Duchartre has recently brought out in reproduction with the imprint of his own publishing house, Duchartre et Van Buggenhoudt, of Paris. The Recueil is the result of the unhoped-for discovery by M. Agne Beijer of a magnificent in-folio album which was in the uncatalogued reserves of the Museum of Stockholm. It was made by a certain M. Fossard for Louis XIV, and, so far as is known, it had never been published, nor had more than two of the engravings ever been found in any other work.

DUCHARTRE'S admirable study of the Italian comedy is already well known in the original to those interested in the subject, particularly in Europe, and surely it deserves the wider attention and appreciation which a version in English can provide. The present volume offers several advantages over the two French editions of La Comdie italienne, in that the author has made extensive corrections and added fresh material to the text. He has been good enough to add also twenty-six entirely new illustrations, most of which have never before been published. It is worth mentioning in passing that nine of these, and two figures which appeared in the second French edition, are taken from a rare collection of sixteenth-century engravings called the Recueil Fossard, which M. Duchartre has recently brought out in reproduction with the imprint of his own publishing house, Duchartre et Van Buggenhoudt, of Paris. The Recueil is the result of the unhoped-for discovery by M. Agne Beijer of a magnificent in-folio album which was in the uncatalogued reserves of the Museum of Stockholm. It was made by a certain M. Fossard for Louis XIV, and, so far as is known, it had never been published, nor had more than two of the engravings ever been found in any other work. ARLEQUIN and Columbine, Isabelle and Scaramouche, Pulcinella and Pantaloon, belong definitely to romance. Behind their names are heard the guitars of the Ftes Galantes, the lingering echoes of shouts, applause, and robust laughter. Yet, as in a Watteau picture, the charm and gaiety of far-gone days die away on a minor key, for those who bore these names are long since dead, and with them all their joyous fantasy.

ARLEQUIN and Columbine, Isabelle and Scaramouche, Pulcinella and Pantaloon, belong definitely to romance. Behind their names are heard the guitars of the Ftes Galantes, the lingering echoes of shouts, applause, and robust laughter. Yet, as in a Watteau picture, the charm and gaiety of far-gone days die away on a minor key, for those who bore these names are long since dead, and with them all their joyous fantasy.