The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Tanisha

Contents

Introduction

Play That Funky Music

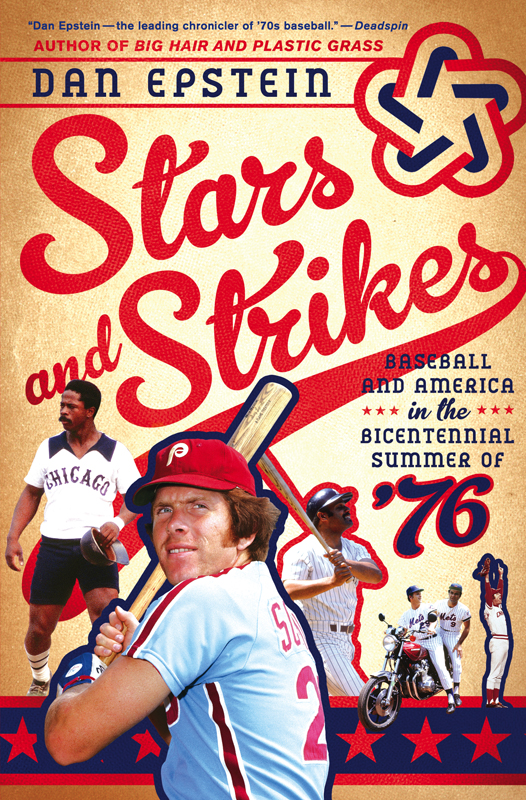

Why 1976? For me, it all goes back to a friends birthday party in April of that year. Tims parents, a couple of freethinking post-hippie types, piled a bunch of us fourth graders into their customized Dodge conversion van and took us all to see The Bad News Bears at Ann Arbors Fox Village Theatre. When we returned to their house, our minds suitably blown by the experience of seeing kids who looked and talked (and best of all, swore ) like us on the big screen, we each received wax packs of Topps baseball cards as party favors. The next day, my father patiently explained to me how to read the stats on the backs of the cards, and my transformation into a full-fledged baseball freak had officially begun.

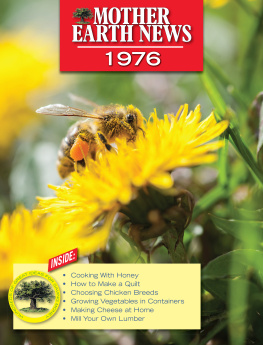

Nineteen seventy-six was the year I got my first baseball mitt, a cheap two-tone orange-and-burgundy Bud Harrelson model ordered from the Sears catalogue; I attended my first major league games in 1976, and read my first issue of the Sporting News while grooving to the Top 40 sounds emanating from my AM transistor radio. By sheer luck, it also happened to be the year in which Mark The Bird Fidrych became a bigger pop-cultural sensation than Dorothy Hamill, Bruce Jenner, and The Fonz put together, Padres lefty Randy The Junkman Jones seemed (for a few months, at least) on course for 30 victories, and Mets slugger Dave Kong Kingman pierced the ozone with tape-measure home runs, while new Braves owner Ted Turner and returning White Sox owner Bill Veeck lured fans to their ballparks with one bizarre promotion after another. Billy Martin led the New York Yankees to the postseason for the first time since Lyndon Johnson was president, Danny Ozarks Philadelphia Phillies and the Whitey Herzoghelmed Kansas City Royals emerged as exciting contenders, and Sparky Andersons Big Red Machine rolled to its second straight World Championship. In other words, it was a tremendously thrilling time to be a ten-year-old boy immersing himself in the myriad joys of the summer game.

Nineteen seventy-six, of course, was also the year of the Bicentennial, that nonstop nationwide party celebrating the United States of Americas 200th birthday. But while we were all wrapping ourselves in red, white, and blue and saluting our Founding Fathers, our country was moving through a year of heavy political, social, and cultural transition. We were finally (or so we thought) putting the divisive era of Richard Nixon and the Vietnam War behind us, and searching for a renewed sense of optimism and connection in everything from CB radio and Frampton Comes Alive! to Olympic glory, Jimmy Carters presidential run, and Rocky . No longer at war anywhere in the world, and with the Cold War beginning to thaw, we focused our collective paranoia on things like busing, urban crime, swine flu, and Legionnaires disease. Disco and punk rock, two of the decades most importantand divisivemusical movements, were cooking in New York City and elsewhere, though they wouldnt reach full boil for another year; hip-hop, which wouldnt explode until the early 80s, was already rocking hard amid the burned-out neighborhoods of the South Bronx.

Nineteen seventy-six was also a crucial transitional year in baseball history, one in which the players finally won their war against the reserve clause despite the best efforts of the owners (and Commissioner Bowie Kuhn), thereby ushering in the free agency era and radically altering the games economics forever. It was a year in which San Francisco nearly lost the Giants to Toronto, and the city of Seattle successfully sued the American League for a new franchise. It was a year that witnessed the reopening of Yankee Stadium, and the final games of future Hall of Famers Hank Aaron, Frank Robinson, and Billy Williams. It was a year in which Oakland As owner Charlie Finleyhaving almost single-handedly built one of the greatest dynasties in baseball historyproceeded to dismantle it like a stolen car in a chop shop.

Yet 1976 is also a year that remains woefully underappreciated by baseball historiansprimarily (or so Ive long suspected) because its World Series was a one-sided affair that ended an exhilarating season on a dour and chilly note. While writing Big Hair and Plastic Grass: A Funky Ride Through Baseball and America in the Swinging 70s , I realized that the 1976 season was so rich with electrifying moments, oddball events, and unforgettable charactersall set against the star-spangled backdrop of the Bicentennialit truly needed (and deserved) a book of its own. After all, what other season can you name that featured a Headlock and Wedlock promotion, major league players wearing Bermuda shorts, and not one but two Harpo Marx look-alikes starting against each other in the All-Star Game?

Ah, but Im getting ahead of myself. Why dont you just kick back on that red-white-and-blue shag rug, pop in that eight-track of the first Boston album, pour yourself a glass of Mateus ros, and get better acquainted with baseball in the Bicentennial? Ill leave you two alone now

Prologue

More Than a Feeling

(October 14, 1976)

Please do not throw bottles on the field, implored Yankee Stadium PA announcer Bob Sheppard, right as something that looked suspiciously like a freshly emptied bottle of Night Train grazed the leg of Kansas City Royals right fielder Hal McRae.

The restless Bronx crowdwho had already given vent to their tension and frustration over the Yankees blown lead by hurling paper cups, batteries, empty beer cans, and lit firecrackers onto the playing fieldresponded to Sheppards entreaties on this chilly Bronx night with jeers, not to mention additional projectiles.

Over in the Royals dugout along the third base line, KC skipper Whitey Herzog watched several umpires and members of the stadium grounds crew scramble to pick up the scattered trash, and debated whether to pull his team off the field. Across the diamond in the Yankees dugout, Billy Martin simply stewed. This was supposed to be the year that the Bronx Bombers returned to postseason glory after over a decade in the doldrums, and Martin was supposed to be the manager that would lead them to the Promised Land. The Yankees had owned the AL East since the middle of April, and theyd been heavily favored to beat the upstart Royals in this best-of-five American League Championship Series.

And yet, after a series marked by controversy, bad blood, and even bomb threats, here they were: tied 66 going into the bottom of the ninth inning in the series fifth and final game. Tonights victors would fly to Cincinnati tomorrow to meet the defending World Champion Reds in the World Series. The losers? Martin didnt even want to think about that. Hed already lost 20 pounds over the course of the season, the stress of dealing with Yankee owner George Steinbrenner driving him to subsist largely on a diet of scotch and cigarettes.

The temperature had slid into the mid-30s during the three hours since the games first pitch, but Telly Savalas didnt seem to mind. The star of the CBS detective drama Kojak was seated behind the Yankees dugout, swathed in a massive fur coat that would have made any uptown pimp turn lime green with envy. Telly remained defiantly hatless despite the cold, his trademark bald dome glistening in the glare of the stadiums lights as he flashed his Who Loves Ya Baby? grin at the rival ABC networks cameras.