Copyright 2010 by Randi Hutter Epstein, M.D.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First published as a Norton paperback 2011

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com

or 800-233-4830

Book design by Judith Stagnitto Abbate

Production manager: Anna Oler

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

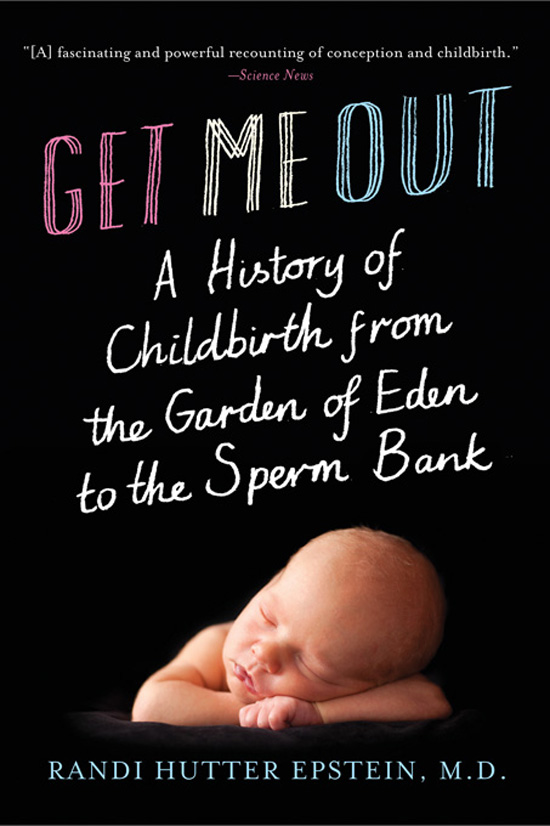

Epstein, Randi Hutter.

Get me out : a history of childbirth from the Garden of Eden

to the sperm bank / Randi Hutter Epstein.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-393-06458-2 (hardcover)

1. ChildbirthHistory. I. Title.

RG651.E67 2010

618.2009dc22 2009034751

ISBN 978-0-393-33906-2 pbk.

ISBN 978-0-393-07990-6 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

To Stuart, Jack, Martha, Joseph, Eliza

Contents

Introduction

In 1889, a woman in northern England gave birth to a boy whose head came out draped inside a piece of the amniotic sac. Typically, if a piece of the sac sticks to the newborns head, a nurse washes it away. Long ago, they were called and were considered either really lucky or really ominous, depending on your birth guru. Some people carried their cauls for good luck because they were supposed to prevent drowning. You could buy someone elses if you werent lucky enough to be born with one.

There was a market in amniomancyforecasting the babys life by reading his cauland it goes back a long way. In AD 208, a Roman emperors son was born with a sac on his head, and everyone celebrated because they figured that the boy was destined for greatness and by extension so was the familys dynasty. As predicted, the boy joined his father as co-emperor by age 9, but father and son were murdered the following year. Whatever. Caul believers continued to keep the faith. By the Middle Ages, doctors poked fun of the folksy caul forecasters, but their cynicism did not deter those who wanted to believe, who wanted to see the future in pregnancy leftovers. In 1658, Sir John Offley bequeathed his daughter a Caul that covered my face and shoulders when I first came into the world.

As it happened on that day in 1889, the local newspaper reported that Not only was the babys head stuck inside his sac, but according to the local newspaper, the caul had these words inscribed on it: British and Foreign Bible Society. The writing was on the wall, or the sac, as the case may have been. Except for one glitch. A skeptical doctor investigated the labor room and realized that the caul had been placed on a Bible with those very same words embossed on the cover. No matter, the townsfolk still considered it propitious. No one let the facts get in the way of a miracle. Or, as the Leeds Mercury reported, The inhabitants still ascribe the affair to supernatural influence and declare that the child is a missionary born and that they will evidentally watch his career with a great amount of interest.

Thomas Forbes, the late Yale anatomist and medical historian, once said that the history of obstetrics is in large part a . He had a point. In ancient times, men who wanted a boy drank red wine spiked with dried rabbits wombs and read guidebooks that told them how to have sex to ensure simultaneous orgasms, considered a must for conception. Pregnant women tried to think happy thoughts to make happy babies and avoid staring at ugly things to prevent ugly babies. As Forbes explained, in the old days before scientific explanations were available, speculation had to suffice, and superstition was often a result.

True enough. But how far have we really come? I dont mean to suggest that every ultrasound and piece of advice is based on superstition. Childbirth, then and now, is a wonderful blend of custom and science. Get Me Out is about the evolution of advice and the advances; the choices couples have been offered; and the decisions they have made. The way expectant parents have chosen to give birthor the way they have negotiated with their caregiversreveals the lengths they will go in their desire, at times desperation, to create the ideal offspring. This is a book about the history of the fears, disappointments, tragedies, and glees. It is about birth, which includes sex, life, and sometimes death. Get Me Out , then, is not a catalog of old-fashioned and often strange words of wisdom, but an examination of how ideas about pregnancy and birth shed light, directly and obliquely, on contemporary society.

Sometimes birth choices are not about perfection or fears but just the way we happen to be living then. In Colonial days, when a womans job was to get married, make babies, and in between pregnancies help her parturient friends, new mothers stayed in bed for weeks on end. They called the postpartum phase confinement, because women were confined. Toward the end of the twentieth century, when women wanted to get back to work (or at least out of the labor room), it became medically okay to get out of bed right away. Were there scientific studies to prompt the change? I should think not. We did what made sense for our lifestyle.

Sometimes its about how we imagine the ideal birth. There was a time in the early 1900s when feminists demanded their right to be knocked out with drugs during delivery. They and physician advocates claimed that the drugs were healthier for mom and for baby. Contrast this to the late 1900s, when feminists railed against painkillers that made them miss part of the birth experience. And they, too, claimed that their way of a drug-free birth was healthier for mom and for baby.

Sometimes its a statement about how couples think pregnancy should be experienced. When first introduced Lamaze to America in the early 1950s, the few folks who heard about her crusade thought it was a silly idea and even fewer tried it. Bing said that the men and women who attended her classes in the early days went because they figured it couldnt hurt, not because they believed. By the 1970s, she was teaching to a sold-out celebrity-studded audience who had faith in the system. Nowadays, Lamaze is a household name, but few husbands are counting in the Lamaze way by the bedside, and much to Bings chagrin, they do not have time for weekly seminars. There was a time in the late 1990s when she was flooded with calls from harried couples who wanted to learn her tricks, but the CliffsNotes version, a quickie one-night session.

Get Me Out begins with Eve, because she started the whole birth-is-painful thing, and concludes with young couples today who sperm-shop and freeze eggs for one reason or another. While I include a few chapters on birth in the early years, the crux of the book focuses on the late nineteenth and the twentieth centuries in America because thats when everything started to change. Scientists discovered germs, and shortly thereafter doctors decided birth should be hygienic. Feminists crusaded for womens rights and began telling birth attendants what to do. Obstetricians went from placing a stethoscope on the belly to listen for the pitter-patter of a heartbeat to using ultrasonography to snap a 3-D image of the fetal heart. Birth went from home to hospital, from drug-free to drugs on delivery, from midwives to doctors, from the occasional C-section to C-sections on demand. On the most superficial level, the huge changes in the birth process reflect the rise of the urbanization, feminization, and technologicalization of American society. On a more profound level, the way we give birth is a story about our deepest desires and our fundamental concerns about life, death, and sex. We are creating life and we will do anything that we think is in our power to control and to perfect the outcome.

Next page