All rights reserved. Potomac Books is an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press.

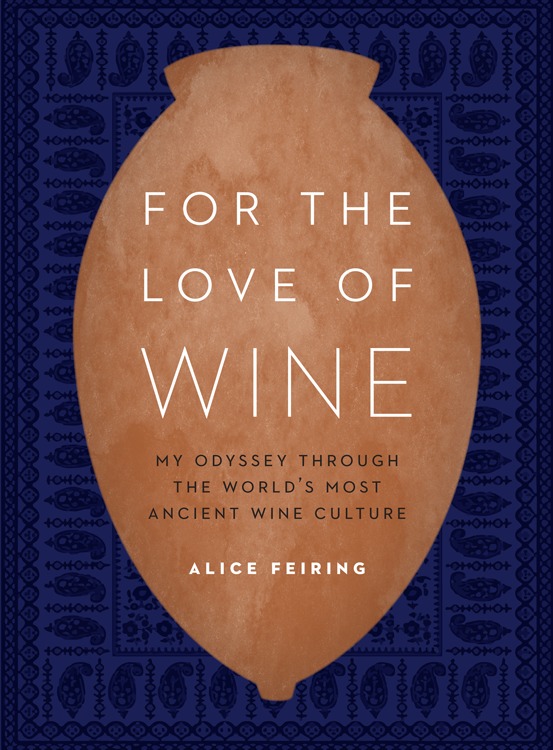

Feiring, Alice, author.

For the love of wine: my odyssey through the worlds most ancient wine culture / Alice Feiring.

ISBN 978-1-61234-764-6 (cloth: alk. paper)

1. Wine and wine makingGeorgia (Republic)History. 2. Georgia (Republic)Description and travel. I. Title.

TP 559. G 2 F 45 2016

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For my brother, Dr. Andrew Jonathan Feiring

Thats why drinking wine is so important in my films. It brings people together, helps them to discover something new maybe even happiness.

When I told people that I was traveling to Georgia for wine, invariably the response was, Great! Then came the look of confusion as they did a double take and asked, Umm, how far from Atlanta are the vines?

The country of, Id say, then further clarify that this Georgia was not in the United States. Its the one under the Caucasus mountain range, not the Blue Ridge.

Really? They make wines there?

They sure do, and I adore them.

Georgia is a small and rich country, about the size of West Virginia. On the west is the Black Sea. To the north lies Russia. On the southeast is Azerbaijan and to the south are Armenia and Turkey. Save for Russia (even though it does refer to its vodka as wine) all of those countries have an ancient winemaking heritage; wine origins seem to be in that zone. And they are all clamoring to be called the region of origin of wine. But Georgia might have an advantage. Now sitting in the National Museum in the Georgian capital of Tbilisi is the oldest cultivated grape seed, which carbon dating puts between six and eight thousand years old. But whoever ultimately wins that Were the oldest race, Georgia, with its 525 or so indigenous grapes, has the longest unbroken winemaking history. They say it has eight thousand vintages.

What tenacity, despite being battered through centuries by the Ottomans and the Persian Shah Abbas II, who viciously tore up the grapevines, thinking it was from there that the Georgians derived their strength. Theyd been abused under the Russians and then had further suffered the insults of communism. Through it all they never lost their wine tradition. They clung to their ghvino (wine) with such a passion youd think it was their blood. They also clung to a clay pot called a qvevri, in which they made their wine with unfailing devotion.

Reading through Henry W. Nevinsons view of Georgia in his 1920 Peoples of All Nations: Their Life Today and Story of Their Past, I was struck by how little had changed. Nevinson writes the following about Georgia: The chief product was wine. The country seems to run with wine. The grapes are squeezed in primitive presses, cleaned with boughs of yew, and the juice run off into huge earthenware vats sunk in the ground, and big enough to hold a man, for when fermentation is finished and the wine drawn off a man gets into the vat to clean it out. The wine is usually poured into tanned buffalo skins, which are laid upon narrow wooden cars and driven slowly along the mountain roads, joggling as they go.

Except for the tanned skins for transport, the process is pretty much exactly as I witnessed in my own travels. Whats more, now, as then, the country seems to run with and on wine. According to historian David Turashvili in his book His Majesty Georgian Wine, customarily Georgians would first ask about their neighbors vines and only then ask about their families. Wine is the Georgians poetry and their folklore, their religion and their daily bread.

What do these ancient yet new wines taste like?

There is red and white wine, of course, but the region is most famous for its white wine, which is actually the amber color of rattlesnake venom. Some call it orange. The color comes from making a white wine as a red wine, with skin contact (see chapter 1). This skin contact not only darkens the color but also lends a sturdy texture. Many of the Georgian wines are tannic, like the tannin in a cup of green tea. On the palate there can be sensual explosions of blossom water and honey without the sweetness; there can be exotic, church-evocative spices of myrrh and frankincense and often a nut of juiciness in the middle.

The reds are far from stereotypical, ranging from large and powerful to delicate and light. Flavors can call to mind the desert or the mountains. But with so many different varieties of grapes and variations of soils, theres a spectrum of tastes.

In a traditional winery one wont find the familiar wooden barrels. Instead the historical and favored vessels for fermentation and storage are the qvevri, the huge earthenware vats sunk in the ground that Nevinson wrote about. They are particular citron-shaped amphoras, made of the local terra-cotta, sealed, sanitized on the inside with propolis, and strengthened with a lime paint or concrete on the outside. They are buried in the ground, where they can survive safely as long as there are no earthquakes, for generations. And now the qvevri have a stamp of approval from the United Nations.

In 2013 the United Nations acknowledged their importance by awarding the qvevri a place on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list. Ultimately the award is no more than a bit of applause for the home country and a vote that says, Hey, world, the qvevri needs to survive. So along with the Argentine tango and traditional violin making in Cremona, as well as the polyphonic songs of Georgia, this, the original container for making wine, is deemed not to be just a museum piece but also a living tradition. Clay not just in qvevri, but particularly in qvevri is having its star moment.

The winemaking world is currently crazy for making wine in clay pots, qvevri or otherwise. There is someone making them in Texas. An Italian company named Clayver is producing and marketing a variant on the clay qvevri that it claims is an improvement on a vessel that has been performing beautifully for eight thousand vintages. There are conferences on clay vessels in Tuscany. Winemakers from Australia to South Africa, in France and Italy, are making wine in them. There are tastings in London devoted to them. Other nations have a history of making wine in clay; after all, before there was glass, clay was