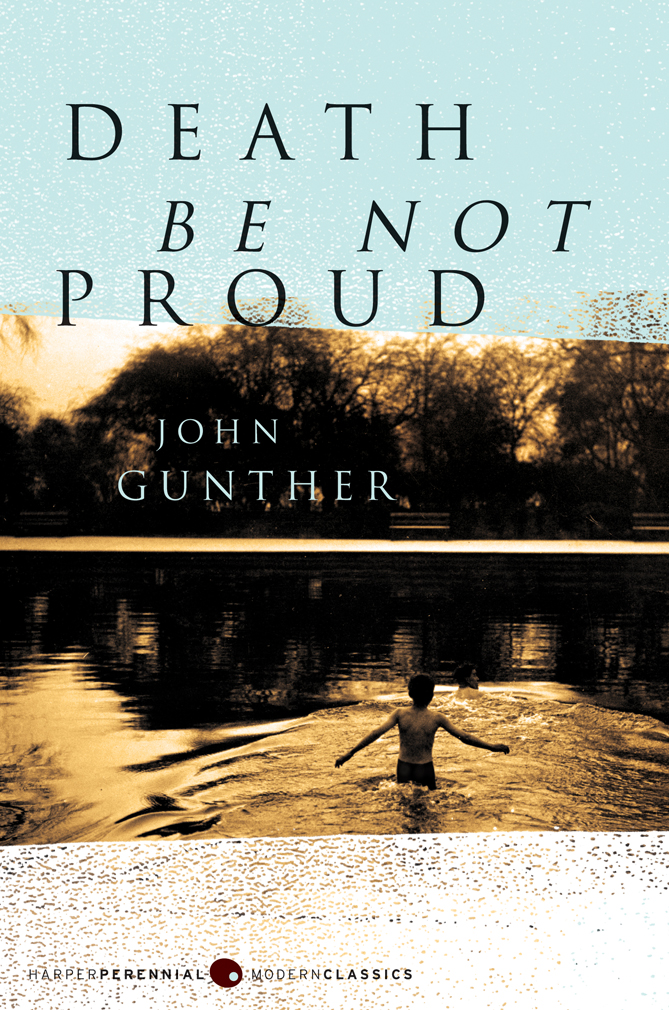

In Memoriam

JOHN GUNTHER JUNIOR

1929-1947

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so:

For those whom thou thinkst thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death; not yet canst thou kill me.

From Rest and Sleep, which but thy picture be,

Much pleasure, then from thee much more must flow;

And soonest our best men with thee do go

Rest of their bones and souls delivery!

Thourt slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell;

And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well

And better than thy stroke. Why swellst thou then?

One short sleep past, we wake eternally,

And Death shall be no more: Death, thou shalt die!

J OHN D ONNE

I want to acknowledge with the deepest thanks the assistance Frances Gunther has given me in preparation of this memoir. It could not have been written without her wise and discriminating help. In particular many anecdotes about Johnny and several of the lines of his dialogue come from her memories and records, which she has generously shared with me.

J. G.

Contents

This is not so much a memoir of Johnny in the conventional sense as the story of a long, courageous struggle between a child and Death. It is not about the happy early years except in this brief introduction, but about his illness. It is, in simple fact, the story of what happened to Johnnys brain. I write it because many children are afflicted by disease, though few ever have to endure what Johnny had, and perhaps they and their parents may derive some modicum of succor from the unflinching fortitude and detachment with which he rode through his ordeal to the end.

Johnny was conceived in California, carried across the bosom of the American continent and the Atlantic Ocean by his mother, and born in Paris, on November 4, 1929. We moved to Vienna when he was a few months old, and he went to kindergarten there and had splendid holidays in the Austrian Alps. We moved again to London when he was six, and he had a year and a half in England. Then we returned to the United States. Johnny went to the public school in Wilton, Connecticut, and to several other schools, including Lincoln in New York City, which he loved with all his heart, and finally to Deerfield Academy, in Deerfield, Massachusetts. He died on June 30, 1947, when he was seventeen, after an illness that lasted fifteen months. He would have entered Harvard last autumn had he lived.

I must try to give you a picture of him. He was a tall boy, almost as tall as I when he died, and skinny, though he had been plump as a youngster, and he was always worried about putting on weight. He was very blond, with hair the color of wheat out in the sun, large bright blue eyes, and the most beautiful hands I have ever seen. His legs were still tall hairy stalks without form, but his hands were mature and beautiful. Most people thought he was very good looking. Perhaps as a father I am prejudiced. Most people did not think of his looks, however; they thought of his humor, his charm and above all his brains. Also there was the matter of selflessness. Johnny was the only person I have ever met who, truly, never thought of himself first, or, for that matter, at all; his considerateness was so extreme as to be a fault.

There was that day after the first operation, the operation that lasted almost six hours, when Dr. Putnam thought it wise to tell him what he had. Johnny was too bright to be forestalled by any more myths or euphemisms. As delicately as if he were handling one of his own instruments of surgery, Putnam said quietly, Johnny, what we operated for was a brain tumor.

Nobody else was in the room, and Johnny looked straight at him.

Do my parents know this? How shall we break it to them?

Then, some months later, when he seemed to be getting better, he felt the edge of bone next to the flap in the skull wound, and looked questioningly and happily at the doctora different doctorthen attending him. The doctor was pleased because the bone appeared to be growing back, but with a crying lack of tact he told Johnny, Oh, yes... its growing... but in the wrong direction, the wrong way.

Johnny controlled himself and said nothing until the doctor left the room. His face had gone white and he was sick with sudden worry and harsh disappointment. Then he murmured to me, Better not tell Mother its growing wrong.

I do not want this brief foreword to be a Bright-Sayings-of-the-Children essay or the kind of eulogy that any fond and bereaved parent may be forgiven for trying to put on paper. What I am trying to tell, however fumblingly and inadequately, is the story of a gallant fight for life, against the most hopeless odds, that should convey a relevance, a message, a lesson perhaps, to anybody who has ever faced ill health. But to do this I must first stake out a few facts about Johnny and give the reader some detailed impression of his character. I want to make some part of him come alive again, if only in the feeble light of words. So let me go back briefly into the moist net of memory.

I have been rummaging this past month through all the papers and things he left, things we had saved and treasured from his earliest daysthe notebook Frances kept recording his weight and height and other such memorabilia when he was an infant, the first drawings he made, the earliest snap-shots, then evidences of his schoolwork, his letters, his report cards and themes and diaries. Here on my desk is a book-mark, bright with enameled colors, that his beloved Austrian governess helped him make when he could not have been more than two; here also his very last chemical formulae and mathematical computations and calculations, which are far beyond my lay comprehension.

Johnnys first explorations of the external world were in the form of picturesgraphic art. Some of his paintings still hang on the walls in the house in Madison, Connecticut. The violence with which a child sees nature! The brilliant savagery of the struggles already precipitated in an infants mind! Here are tigers of the most menacing ferocitybloody, chewing up baby lambs, with their red jaws open and foaming; then by contrast a group of somnolent, placid, herbaceous elephants; then landscapes mostly in green, with blue trails leading to jagged mountains, and a dirigible soaring in the sky; then boats dancing on blue water, boats with multitudinous white shining sails. Later came airplanes, locomotives, heavy trains. Johnny always had an acute interest in transportation. One of his earliest concepts was Smoky, a magic personification of a machine that conquered all frontiers of time and space.

Music came next. Not all children are Mozarts; but almost all are geniuses at one thing or another before they are ten. Johnny had a considerable musical talent, though he did not push it far. He was, like the youngster in Aldous Huxleys beautiful story Young Archimedes, more interested in the structure of music, in its mathematics, than in playing tunes or listening to melodies. He took violin lessons early and kept his precious recorder close to him till the day he died. When he was about ten he became fascinated with the woodwinds, especially the bassoon. For years his ambition was to own and play a bassoon; this instrument, however, does not exist in miniature form, and of course he was never able to handle one. But he saved regularly out of his allowance to buy one later. He would sit by the hour listening to woodwind music, and we bought him practically every record that exists in which the bassoon is prominent. I remember coming home one day with the Schubert Octet, Opus 166. He listened to it, rocking with excited glee, Oh, boy! Oh, boy! Next year he was hard at work composing; in April, 1940, he finished what he called the rondo of his first symphony. Later that year he played several of his own compositions at a Lincoln School recital. I was doing a job somewhere and called him on the phone to say that, unhappily, I could not get back to New York in time to hear him. He replied drily, You could certainly get here if you hired an airplane.