Table of Contents

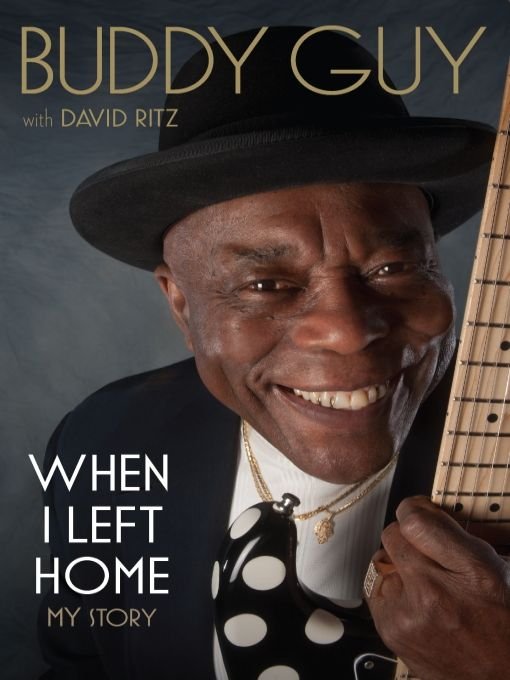

In memory of Muddy, father to us all

Preface

I get up at break of dawn. Been doing that my whole life. Thats what happens when you grow up on the farm. Circumstances might change, but if you a country boy like me, you still hear the rooster.

My house is way on the outskirts of town in the far suburbs of Chicago on fourteen acres of land. Looking out the backyard I see trees everywhere. Got a thing for trees. I like watching how the leaves turn color in the fall, how winter frosts over the branches, how little buds break out in spring and new leaves come to life in summer. The seasons got a rhythm that connects me to the earth.

First thing on my mind are beans. Thinking about going to the store to buy beans. If I find some freshly shelled beans, Ill jump over the counter to get em. Get to the supermarket when the doors first open. Someone might recognize me, might say, Buddy, what you doing here? I say, Hey, man, I gotta eat like everyone else. Gotta get me some fresh beans.

When the weathers warm, I want melon. But you cant sell me melon without seeds. Just like you cant sell me white-and-yellow corn. I dont fool with no food thats messed over by man. On the way home, if I see a stand on the side of the road, Ill stop to see what they got. If they got corn and I spot a little worm crawling over the top, Ill buy it. That means the corn hasnt been sprayed with chemicals. Its easy to clean out the worm, but how you gonna clean out the chemicals?

Ill spend the rest of the day in the kitchen. Maybe Ill cook up a gumbo with fresh crayfish. When I was a boy, crayfish tail was bait. Now its a delicacy. The rice, the spice, the greens, the beanswhen I get to cooking, when the pots get to boiling and the odors go floating all over the house, my mind rests easy. My mind is mighty happy. My mind goes back to my uncle, who made his money on the Mississippi River down in Louisiana where we was raised. My uncle caught the catfish and brought it home to Mama. That fish was so clean and fresh, we didnt need to skin it. Mama would just wash it with hot water before frying it up. I can still hear the sound of the sizzle. And when I bit into that crispy, crackling skin and tasted the pure white of the sweet fish meat, I was one happy little boy.

Thats the kind of food Im looking for. Im looking today, and Im looking tomorrow, and Ill be looking for the rest of my life.

My life is pretty simple. If Im off the road and not getting ready to go off to New York or New Delhi, Ill spend my day shopping and cooking. Maybe the kids will come over. Maybe Ill eat alone. At 2 p.m. Ill take me a good long nap. After dinner Ill get in my SUV and see that Ive put some 200,000 miles on the thing. If its low on gas, Ill take the time to drive over to Indiana where gas is a couple of cents cheaper. Ill remember that one of my first jobs off the farm was in Baton Rouge pumping gas. Back then the average sale was $1. Today itll cost me $120 to fill the tank. Aint complainingjust saying Ive seen some changes in these many years Ive been running this race.

Around 7:30 Ill head into Chicago. My club, Legends, sits on the corner of Wabash and Balbo, right across from the huge Hilton Hotel on the south end of the Loop. Its a big club that can hold up to five hundred people, and Im pleased to say that I own the building that houses it.

I go in and take a seat on a stool in the back. I say hello to the men and women who work there. Two of my daughters run the place, and theyre usually upstairs going over the books. Occasionally a customer will recognize me, but to most everyone Im just a guy at the bar. Thats how I like it. I dont need no attention tonightIm not playing, Im just kicking back. Im feeling good that I got a place to go at night and that Chicago still has a club where you can hear the blues. Live blues every night. Cant tell you how that warms this old mans heart.

Funny thing about the blues: you play em cause you got em. But when you play em, you lose em. If you hear emif you let the music get into your soulyou also lose em. The blues chase the blues away. The true blues feeling is so strong that you forget everything elseeven your own blues.

So tonight Im thinking about how the blues change you and how they changed me. Thinking about how I followed the blues ever since I was a young child. Followed the blues from a plantation way out in the middle of nowhere to the knife-and-gun concrete jungle of Chicago. The blues took my life and turned it upside down. Had me going places and doing things that, when I look back, seem crazy. The blues turned me wild. They brought out something in me I didnt even know was there.

So here I ama seventy-five-year-old man sitting on a bar stool in a blues club, trying to figure out exactly how I got here. Any way you look at it, its a helluva story.

Before I Left Home

Flour Sack

You might be looking through a book of pictures or walking through a museum where they got photographs of people picking cotton back in the 1940s. Your eye might be drawn to a photo of a family out in the fields. Theres a father with his big ol sack filled with cotton. Theres a woman next to himmaybe his wife, maybe his sister. And next to them is a boy, maybe nine years old. He got him a flour sack. Thats all he can manage. After all, its his first day picking.

That little boy could be me. I started picking at about that age. I stood next to my daddy, who showed me how to do the job right.

Depending where you coming from, you could feel sorry for that little boy, thinking hes being misused. You could feel hes too young to work like that. You could decide that the world he was born intothe world of sharecroppingwas cruel and unfair. And you wouldnt be entirely wrong. Except that if that boy was me and you were able to get inside my little head, youd find that I was happy being out there with my daddy, doing the work that the big people did. I wanted to be grown and help my family any way I could. Didnt know anything else except the land and the sky and the seasons and the fruits and the fish and the horses and the cows and the pigs and the pecans and the birds and the moss and the white cotton that we prayed came up plentiful enough to give us enough money to make it through winter.

I saw the world through the eyes of my mama and daddy. Their eyes were looking at the earth. The earth had to yield. If it did, we ate. If it didnt, we scrambled. Because we didnt have no electricitynot for the first twelve years of my lifewe were cut off from what was happening outside our little spot in Louisiana called Lettsworth. I didnt know it at the time, but we were living and farming like people lived and farmed a hundred years before. When I got my little flour sack and went out in the field, I was doing something my people had been doing ever since we were herded up like cattle in Africa, sent out on slave boats, and forced to work the land of the southern states of America. That fact, though, was something that came into my mind when I was an adult playing my music in Senegal. Someone brought me to the Point of No Return, one of the places where slaves were sent off to make that terrible Atlantic crossing. Maybe thats where the blues began.

But to menine-year-old George Buddy Guy, son of Sam and Isabell Guy, born July 30, 1936black history was not part of the elementary schooling I got at the True Vine Baptist Church. Thats where I was taught to use utensils and read little books about white children called Dick and Jane. Black people werent in those books. Blacks werent part of history. All we knew was the present time. We knew today, and today meant shuck the corn and feed the pig and go to school in the evenings after our chores were done.